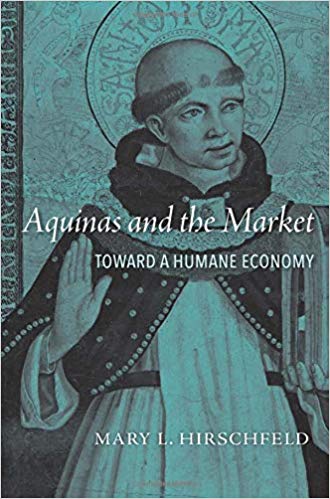

Aquinas and the Market: Toward a Humane Economy. By Mary L. Hirschfeld. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018. Xviii + 268 pages. $45.00.

This review originally appeared in the Journal of Moral Theology January 2020 issue.

In Aquinas and the Market, theologian and economist Mary Hirschfeld makes the case for a version of Thomism to rightly order the relationship of theology and economics and offers a coherent moral vision for economic decision-making. Hirschfeld sees the problem as one of fragmentation (following Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age). Each sphere of human life, to include economics, operates as if possessing its own internal rationality without reference to some larger whole. Thus, economic prosperity has become for many the highest common good, as the social good that enables persons to pursue their individual good. While a broad scholarly consensus exists among economists, theologians, Hirschfeld notes, are as fragmented as ever.

Hirschfeld maps out this fragmented landscape and sees three broad approaches to economics. The first approach relies on the well-known premises of economic thought and is either dismissed by economists as disastrous in its real-world forms (e.g., the use of Marxism) or as simply a less robust version of capitalism. Helpfully, however, this approach seeks to overcome fragmentation, finding harmony between economic and theological discourses. The second approach places theology and economics in an ends-means relationship. Theology sets the agenda for the normative ends, while economists are put to work modeling the proper means. For Hirschfeld, this approach goes wrong when theologians do not contain themselves to setting out ends. The third approach uses theology to critique economic premises. As an economist, Hirschfeld knows the incredible power of economic modeling and is unwilling to set it aside for moralism or utopian thinking. As a theologian, however, she is compelled to demand that the market serves human flourishing and affirms theological impulses to offer critical perspectives on the economy. Hirschfeld thinks her Thomistic approach is capable of bringing together the best aspects of all three.

Hirschfeld begins by examining Thomas’s treatise on happiness in the Summa Theologiae in order to set economics within the context of Thomas’s account of human flourishing. She finds common ground between economic and Thomistic anthropologies in that both are teleological. She sees both as broadly eudaemonistic and brings them into relation by arguing that the goods of the homo economicus are really instrumental and subordinate to the pursuit of the ultimate good of human life, God.

In chapter two, Hirschfeld provides an overview of modern economic thought with an in-depth analysis of the rational choice model. She argues that, while economics claims scientific objectivity, even the supposedly descriptive work of economics is rife normative claims. Moreover, she shows how economics fails to account for human behavior beyond self-interest and flattens all human desire to the same scale of value, utility maximization.

In chapter three, Hirschfeld sets the theological stage by offering an overview of Thomas’s eudaemonistic account of human agency and its metaphysical underpinnings. Humans are created to image God (imago Dei). Happiness is in realizing this potential in act. Here she unpacks Thomas’s account of virtue.

In chapter four, Hirschfeld contrasts prudence and rational choice. She finds the descriptive power of rational choice theory to be its real insights about a lower form of practical reasoning, but she thinks that rational choice is incapable of accounting for prudential judgments. The perfection sought through virtue resists the logic of utility maximization. Thomas’s anthropology can account for the pursuit of instrumental goods described by rational choice theory, but subordinates this aspect of human practical rationality to the prudential wisdom that leads to the knowledge and love of God.

Hirschfeld goes on, in chapter five, to give an account of wealth that is ordered to human virtue and the happiness of life with God. It is here that she seeks to bind mammon to the service of real human material needs. Just as material wealth is instrumental to the pursuit of virtue, so too is the exercise of virtue perfected through material relations.

Thomas’s account of property takes up chapter six. Property is not its own end, but the means for providing the necessities of life for oneself, one’s family, and–where there is excess–other more distant neighbors. For Thomas and Hirschfeld, surplus belongs the impoverished as a matter of justice. To bring Thomas forward on this point, Hirschfeld draws out an account of just wages and just prices. She advocates for prudential judgment and, while not putting it precisely this way, an inclination toward downward mobility.

Finally, in chapter seven, Hirschfeld concludes by placing economics within the Thomistic framework she has just developed, setting out practical ways economics might be rightly ordered to virtue.

Hirschfeld points us in the right direction. The relationship between Christianity and capitalism is too complex to simply assume the premises of capitalism, use capitalism as a means for Christian ends, or oppose capitalism entirely. Hirschfeld’s Thomistic account of the relationship between economics and theology offers a compelling way to integrate all three approaches. Hirschfeld’s work is to be praised and will hopefully spur genuine conversation between theologians and economists.

ADAM D. TIETJE

Duke Divinity School