Isaiah 22:19-23

Psalm 138

Romans 11:33-36

Matthew 16:13-20

One could quite easily take a triumphalistic and institutional approach to this Sunday’s readings, which all deal in some way with the supremacy of God’s authority and the legitimacy of its delegation to human beings. In the Catholic mode, this approach would center upon Christ’s bestowal of “the keys to kingdom of heaven” upon the now-renamed Simon son of Jonah, thus establishing the Petrine office in which the divine authority of the Church has henceforth been centered. God does this sort of thing from time to time, as the first reading from Isaiah indicates: Shebna is stripped of his authority as master of the royal palace, and his office is then given to Eliakim son of Hilkiah. “I will place the key of the House of David on Eliakim’s shoulder,” God declares, “when he opens, no one shall shut; when he shuts, no one shall open.” We as Catholics can therefore celebrate and take comfort from the fact that Christ himself has established in Peter an office that is divinely sanctioned and guaranteed as a vehicle for God’s ongoing work of salvation in human history.

Such a reading, however, floats above the text in a way that threatens to distort the nature of God’s authority, or perhaps more accurately, threatens to import into the scriptural text the prevailing notion of authority operative in our own time and place. Only four chapters on in Matthew’s gospel Jesus will dress down his squabbling disciples with these words:

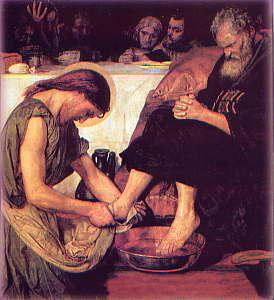

You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great ones are tyrants over them. It will not be so among you; but whoever wishes to be great among you must be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you must be your slave; just as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many.

Greatness and preeminence come not from competitive triumph and domination, but from service, devotion and self-forgetting love. “To serve is to reign:” perhaps the thrust of this old patristic adage is more literal than we think. Perhaps we really can refer to the pope as the “servant of the servants of God” without tongues in our cheeks.

There is a small detail in the exchange between Jesus and Peter which I think beautifully captures the origin and abiding character of this love-borne authority. Jesus is in Gentile-country again, in Caesarea Philippi up near the old Phoenician cities of Tyre and Sidon, and there he asks his followers “who do people say the Son of Man is?”

I am always drawn to that self-styled pseudonym Jesus repeatedly uses throughout the gospels—“Son of Man”— mostly because I am puzzled by it and don’t know what to do with it. I’ll spare you my theories, and point out one consequence of its use here: together with the reference to “people”—the crowds, the public, the hoi polloi— Jesus’ initial question has a very distant, third-person quality to it.

Notice that it really could have been anyone asking it, assuming that others knew and used that particular title for Jesus. Usually we think it either pretentious, unsettling or humorous when people refer to themselves in third person, and even more so when they do it using a pseudonym requiring an indefinite article. (I can’t help but think here of “the Dude” from The Big Lebowski. “Who do people say the Dude is?”) Regardless of its deeper signification, which I am sure is there, the term casts things in the third person. It is a question posed from a distance, almost as if to put the disciples in the position of spectators or analysts.

Then comes the shift, however: “But who do you say I am?” Now the question is posed in the second person; it is about you. And Jesus returns his self-reference to the first person: what do you have to say about me?

This shift is all-important. The identity of Jesus is no longer an academic question, a matter out there somewhere. Rather, it is now a question of you and me, a matter of immediate and urgent significance upon which a relationship hangs. To use a term currently favored by Pope Francis, it is now a question that is put within the context of an encounter.

This encounter between Jesus and Peter reveals the inextricable bond and mutual dependency between truth and love. By answering truthfully, insofar as he is led into the truth by the Holy Spirit, Peter reveals and confirms his bond of love with Jesus. And the encounter also suggests that it is this bond of love-in-truth that is the true basis for the authority that Jesus bestows upon Peter and upon His Church.

It is not the theologian who can deduce and digress upon the correct understanding of “the Son of Man” who is given the authority of the kingdom of heaven. It is the servant who knows Jesus personally, and who can tell him in his presence, “You—you are the Christ. You are the Son of the Living God. Have mercy upon me.” If Christ has indeed given to His Church a power and an authority which not even the gates of hell can ultimately resist, it is not a power of domination and subjugation; it is simply the power of a love borne and sustained in the truth—a love which simply is the ultimate truth of who God is.