Lectionary: 129

Wisdom 9:13-18b

Psalm 90

Philemon 9-10, 12-17

Luke 14:25-33

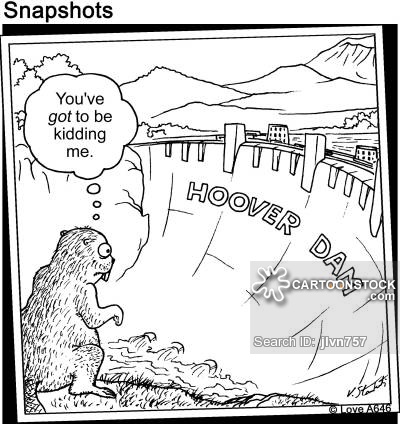

Beavers are amazing creatures. On a walk around a local reservoir with a few of my kids, I saw the traces of their work all around us: the tell-tale conical-topped stumps and the occasional triangular dent in a tree that turned out to be too big for them to bring down. Their energy must be endless; the marks of their activity were everywhere. We saw the same thing when we were exploring the Snake River a couple summers ago, except then we were actually able to see and poke around a recently-abandoned lodge. The intricacy and stability of the structure was astounding. The dome was about as wide as a minivan, and I could climb up (all 200 pounds of me) and stand on the top without feeling the least give. All the planning that seemed necessary to accomplish such a task! And not to mention the engineering required to dam the stream in the first place, and the foresight needed to hoard enough food for the winter! Indeed, beavers are truly amazing.

Ruminating in this way on beavers together with some relatives, the question came up: do they really have any idea what they are doing? Can we really say they “plan” or “engineer” or have “foresight” in any way resembling our understanding of those terms? One cousin suggested that they probably just chew on trees because it feels good, and similarly (though less transparently) they are just responding to blind instincts when they arrange the trees and branches as they do… damming streams and constructing watertight shelters. They have no blueprints, after all, no apparent measuring devices or machines. Whatever guides their work, we can at least safely say that it dwells inside them; whatever it is, they know it by heart.

It is perhaps instructive then to go on think about what distinguishes this inner “something” that instructs the beavers in their work from the motivations, principles and practices that guide our own projects. Of course we should recognize the differences in the scale and complexity of what we humans are able to accomplish along these lines. Not only are we capable of constructing our homes with an endless variation of designs (it would be rather boring if every building was a dome!), but the scale and complexity of our interventions into nature is incomparably greater. Just today I read an article in the newspaper about a proposed hydroelectric dam in Turkey that would submerge the ancient town of Hasankeyf under 200 feet of water: let’s see you do that, beavers! Without a doubt then, we possess the ability to foresee, design, and engineer in a way that far, far surpasses any other earthly creature. But still, should we for that reason not think of ourselves as earthly creatures? Not place ourselves on a continuum with other highly organized animal species such as ants, bees, and beavers?

I would venture to say that the first two lectionary readings for this week invite us to recognize both sides of our existence as a unity of spirit and matter. On the one hand, as the reading from Wisdom reminds us, we desire to know God and His counsel, to “search out the things of heaven” and so “make our paths straight.” Such a desire presumes the capacity to act in a very intentional and ordered way, indeed with the highest ends of creation in mind. But on the other hand, these readings also emphasize the limitations to our ability to “know what we are doing” and to “make things come out right.” “Who can know God’s counsel,” the author of Wisdom asks, “or who can conceive what the Lord intends? For the deliberations of mortals are timid, and unsure are our plans.” Our soul, that which perceives and reaches out toward what is eternal, finds itself hemmed in on all sides—burdened, weighed down—by the demands and contingencies of material existence. “And scarce do we guess the things on earth,” he goes on to say, “and what is within our grasp we find with difficulty; but when things are in heaven, who can search them out?” In other words, even if we can form a general idea of the ultimate end of our lives, how could we possibly know what to do to achieve it?

The answer: only the wisdom that comes as a gift of the Holy Spirit can guide us toward we are made for; only the indwelling presence of God himself can direct our steps to what the Lord intends. And how different really, as a principle of action, is that sort of guidance from the guidance of instinct, what directs the beavers to do what they do? Let me say (before I get in trouble) that the active direction of the Holy Spirit elevates our nature, such that we become higher than we are: more like the angels, and less like non-rational animals. However, there is still an element of surrender involved, as well a certain externality: we must give up control, and allow the Lord to take over. For as the psalm for this week so beautifully reminds us, we are so little and so extremely fragile in the cosmic scope of things. We are like specks of dust, like the blades of grass whose existence hangs tenuously in the balance from hour to hour. What can we really do if want to “number our days aright,” and make sure the balance of sacrifice and reward comes out right in the end? Here the answer is disclosed in the very form of the question: only through prayer can we gain “wisdom of heart.” Only by faithful and trusting reliance upon the Lord can we even have the slightest hope that the work of our hands will ultimately amount to something meaningful.

“Fill us at daybreak with your kindness, that we may shout for joy and gladness all our days. And may the gracious care of the Lord our God be ours.” What a beautiful prayer! And it really sums us what we are left with in terms of insurance policies on existential significance. All we can do is cry out for God, for his presence. But of course, that is what our existence is really about in the end: to share God’s presence. That is why it is impossible to know and find our purpose without the Holy Spirit; and that is why it is impossible for us to secure the final goal of our lives without ongoing dialogue with the Lord.

These readings then set us up nicely for this week’s gospel, which always sounds a little harsh on the surface. Jesus enumerates conditions for those who follow him: “If anyone comes to me without hating his father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, and even his own life, he cannot be my disciple.” Ouch. But I thought Christianity was supposed to be all about unconditional love, not to mention being well-integrated and well-adjusted! The person Jesus just described sounds like a sociopath! Jesus doubles down, though, declaring that “whoever does not carry his own cross and come after me cannot be my disciple.” But perhaps all this is merely poetic, hyperbole.

Almost as if to anticipate such an interpretation, Jesus patiently explains in very pedestrian language that anyone who sets out to do something must first of all assess what it will take to accomplish their goal. Here we are, meditating again upon foresight, planning, logistics. If you want to build something, first you need to have a design and take inventory to see if you have enough money and materials to build what you want to build. Or if you want to win a battle, you first need to assess whether you have enough manpower to execute a successful battle plan. If you don’t first “count the cost” when it comes to these sorts of efforts, you will clearly fail. Right? “In the same way,” Jesus says, “anyone of you who does not renounce all his possessions cannot be my disciple.” Whoa. Really? All my possessions? What does he mean? What is he getting at? What is Jesus doing here?

Is Jesus being greedy? Or is he just trying to “weed out” those who don’t have what it takes to be his disciple? Is it like a first century version of a Marines Corps ad: Jesus looking for a “few good men”? Or is it just a test? But again, doesn’t this approach seem to conflict with the whole universal, unconditional love thing? Well, yes and no. Yes, if we take simply as a matter of sheer toughness, perseverance, and commitment to a cause: Jesus is not just asking his followers to be really, really fanatical or else go home. No, if we think about the conditions for the possibility of the sort of “universal, unconditional” love we have in mind, we will see that what Jesus really wants for us is to consider the requirement of truly mutual love—a communion of persons. What Jesus ultimately wants for is is to be a part of that eternal exchange of perfect love that constitutes the very life of God. But unconditional love that is unidirectional is really not love at all; it is exploitation. (Just go read The Giving Tree to see what I mean.) So yes, in a sense, true unconditional love does have a condition: that what both parties desire above and before all else is each other. Otherwise what we’re dealing with isn’t truly love.

What Jesus wants, what the Lord God of Israel has always wanted, is just one thing: you. And not just part of you, all of you. Hence the beautiful Gospel antiphon for this week: “let your face shine upon your servant, and teach me your laws.” When the “laws” in question are simply an enumeration of the logic of love, then the most important point of focus becomes the other’s “face” and how it regards the one who loves it. It is this kind of love that discloses the ultimate meaning of any and all of the designs we have for our lives. It is the love that longs above all for the Lord’s presence, and can enjoy the goods of the earth only in the light that shines from His face. Truly, apart from the real and active presence of the One who has made and redeemed us, all the designs, treasures and accomplishments of this world are but specks of dust, blades of grass.