(This is the second of a series of posts on Bishop McElroy’s speech.)

Bishop McElroy’s speech, as my colleague so clearly laid out yesterday, is meant to be a rallying cry to American Catholics: a call for discernment and collaboration as the USCCB gathers together in my own backyard, Baltimore, this week. There is much to admire in what Bishop McElroy puts forward, in particular the strong role he wants to carve for lay leadership in the Church. He not only grounds his concept of synodality in baptism, in Lumen Gentium’s universal call to holiness, but he also asserts that “an authentic process of synodality must never be an elite process, for it represents the action of the whole people of God.” Later in the speech, as Bishop McElroy lays out the principle of a “co-responsible and participatory” church, he specifically decries clericalism, and the impact that has not only on lay faithful, but the men and women who feel called to serve the church in their capacities as laypersons. He makes a clear call to strengthen lay ministry precisely because it can re-frame the priesthood and resist clericalism: “for this reason, any process of synodal discernment in the church in the United States must confront forcefully the avenues through which lay ministry and empowerment are enhanced in the concrete life of the church, and how they are frustrated.”

I want to applaud this sentiment wholeheartedly – but also, I am fearful that it is only sentiment. Much of what the bishop ascribed to synodality seems to rest on dispositions and attitudes. I don’t think he’s wrong to identify such problems (e.g., clericalism, or a “bunker mentality”), but I wonder if dispositions are enough to move the Church in the right direction without clear, structural mechanisms for “co-responsibility and participation” as proposed. I firmly believe that lay leadership is the necessary future of our church (a future Bishop McElroy rightly points out the recent Amazon synod is already seeking), yet our bishops have shown great reluctance to involve lay leadership in what I would argue is the deepest wound of the US church: the sex abuse crisis.

To his credit, Bishop McElroy also clearly names this wound, discussing it in conjunction with clericalism, which he calls “a poison that protects abusers of children from detection and justice;” a poison that lay leadership then provides at least a partial antidote for. If synodality is a process for all the faithful and not restricted to an elite few, then I believe to take McElroy’s call seriously requires rethinking the relationship of laity to our bishops in a synodal context. This may require moving beyond dispositions to actual particpatory practices of decision-making.

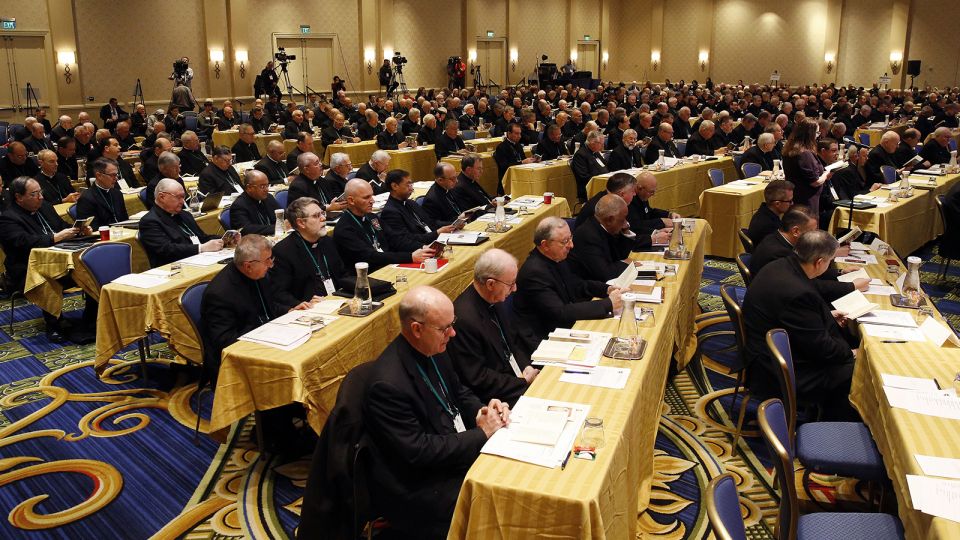

As they currently work, USCCB meetings operate in a similar manner to global synods: they integrate lay leaders in consulting and advisory positions. For example, Francesco Cesareo has attended as the chairman of the National Review Board, which was established following the John Jay Report in 2004 to make recommendations about processes of reporting and adjudicating abuse cases. But when it comes to votes, those rest solely in the hands of the bishops. A lay consultant can exert a persuasive influence, but not a structural one. Bishop McElroy calls synodality “a process of listening” – and our current structure reflects that – but I worry about what happens when the decision-makers who must listen are already susceptible to the very clericalism and bunker mentality that the bishop wants to reject.

This is both a theological and canonical problem for synodality. The current Code of Canon Law dictates that only bishops have a vote in a conference (Can. 454 §1-2), but each conference is to establish its own statutes (with approval of the Holy See, Can 451.). So it is a question for the canon lawyers as to whether it’s within the power of a conference to grant voting power to laypersons, although given the canonical and theological understandings of the episcopacy as the absolute leader of the local church, it seems that inclusion of lay votes in a synod has some significant hurdles. Here we may also find ourselves running into the “culture of maintenance” that Bishop McElory also identifies as a key problem for the Church:

We are also the inheritors of patterns of decision making that place enormous value on how decisions were made in the past as a guide as to how they should be made today. These two realities create in the church a powerful force of inertia that often makes maintaining the status quo a higher imperative than constantly renewing the priorities of the church in the light of the Gospel as applied to today’s ecclesial and societal situation.

This serves not only as a critical question about structures of the synod that might be be susceptible to this inertia, it also a reminder that the power of vote alone doesn’t ensure that lay voices are heard and recognized. Inertia can apply can to laity and clergy.

Nonetheless, I would still argue that the canonical exclusion of lay persons points to a deeper theological problem with synodality that I am not sure McElroy’s principles can overcome: there is no active mechanism for episcopal accountability to the laity other than the good will of other bishops. This has been especially visible in the course of the abuse crisis, and more so since the last meeting of the USCCB in June, where the bishops voted on the implementation of Vos Estis Lux Mundi, Pope Francis’s directives concerning bishops’ accountability. It was something of a scandal when the Vatican seemingly squashed a vote on a USCCB proposal this time last year (prior to the release of Francis’s motu proprio) which is rumored to have had stronger capacities for lay oversight than what was passed in June. The good news is that we have already seen the June guidelines put into action, with the disinvitation of Michael Bransfield, the former bishop of Wheeling-Charleston who left under a cloud of suspicion with accusations of sexual abuse and a great deal of evidence of financial mismanagement. But the protocols passed in June all rely on other bishops – in most cases, the successor to bishops who have resigned in disgrace – taking the lead in restricting the participation (and sometimes ministerial capacities) of emeriti.

In the meanwhile, victim advocates – including aforementioned Cesareo – keep pushing for external audits and oversight. I would argue that Cesareo’s calls for greater accountability actually serve the principles that Bishop McElroy put forward. Last June, Cesareo told Catholic News Service:

[Lay leadership is] not meant to undermine their authority but in reality strengthen their position in dealing with the questions around this issue as opposed to a challenge to their authority or position. That’s not the intent. The intent is how can we together work on this issue to put you, as the leaders, in the best possible position to effectively and definitively deal with this.

This is precisely the kind of reciprocity that McElroy wants to see, a collaboration between lay and clergy that strengthens the mission of the Church. Co-responsibility must go hand-in-hand with participation, with accountability between lay and clergy. Whether it’s fear, a bunker mentality, or a culture of maintenance, the bishops need to start making more practical efforts and structural space for lay leadership, not only with respect to the abuse crisis, but in all areas of the Church’s life and mission.

![[UPDATE 1/23] The Viability of the 20-Week Abortion Ban: Is the GOP Willing to Work to Secure Passage?](https://catholicmoraltheology.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/save-roe.jpg)

Trackbacks/Pingbacks