(This is the third in a series of posts about Bishop McElroy’s speech last Monday.)

A few weeks ago, I went to dinner with two other women from my parish. We knew each other’s faces well, from attending the same mass for several years. We had all three been involved in RCIA, and one evening had gotten into a brief conversation about vocation and being single, as we all three are. One of us suggested that we might get together sometime for dinner.

It seemed like a good idea. It’s not just Pope Francis’ calls for encounter, widespread concerns about polarization, and the chance to make new friends. More fundamentally I saw it as necessary for my participation in the Church as, in the words David Cloutier wrote in the first posting in this series, “the sacrament of the unity of the human race, via living out our baptismal call to holiness.” The Church’s unity isn’t reducible to personal relationships, but it would be difficult to claim to be such a sacrament if one had not ever had dinner with people from the parish. I had not.

So we went to dinner. We just shared a bit of our personal interests, family histories, work situations. We were doing fairly well, until one of the others began talking about a recent business trip to El Paso/ Juarez, in which she had learned that the people camped on the other side of the border had unreasonable expectations about their possible futures in the US which had been fed them by unscrupulous coyotes, and that was why they wouldn’t accept any of the very good other options they had for their lives in Mexico. As it happened, I had just hosted a guest from the Hope Border Institute in El Paso/ Juarez, and I had been with her when she got a call that a client waiting in Mexico for news about refugee status had died, after not being able to access adequate medical care. The conversation that followed was what one could call ‘civil’: no profanities, no broken dishes, no personal insults. But the vibrations of anger and resentment accompanying our short, intense discussion of the realities of “remain in Mexico” policy were like the bass cranked up all the way in a small car until the windows rattle. That exchange put an end to our budding conversation. We haven’t been out again since.

I agree with Cloutier that the unity of the Body of Christ for the life of the world is the ultimate reality to keep in view. I agree even more with Lorraine Cuddeback-Gedeon’s argument that sentiment is not enough; we need structures of synodality, systems of inclusion and accountability.

That is why I want to point us toward a theological understanding of conflict, not as a failure of the calling to unity nor only as a psychological or social reality, but as an essential aspect of participation in the life of Christ, an aspect that needs to be recognized, welcomed, and supported. What happened in the dinner that crashed was a missed opportunity, an evasion of a particularly important species of encounter, the gift of conflict, which is an opportunity to touch the wounds of the ecclesial Body of Christ.

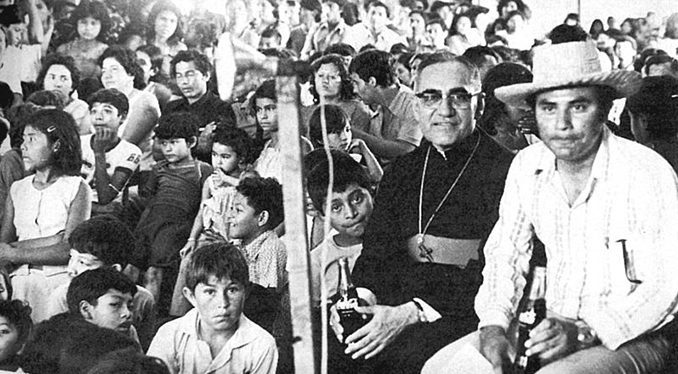

My model for this theology of conflict is St. Oscar Romero. His ministry as archbishop was constantly rocked by conflict in both the Church and in his society. Though he always had a temper, in the later years of his life, his arguments took on a different character. First, they grew from long listening to the gospel and to suffering people. His tenure as archbishop included extensive consultation with his clergy, local religious, and the laity. Having listened, he spoke the truth he had learned, and he spoke it directly and specifically. He didn’t spin it in attempt to win or to avoid fractures. He spoke boldly. He was trying to make contact, to open up new life for his opponents and for the Church.

“It gives me…pleasure that my enemies listen to me. I know that the reason they listen to me is that I bear them a message of love. I don’t hate them. I don’t want revenge. I wish them no harm. I beg them to be converted, to come to be happy with the happiness that you [the congregation] have.” (Oscar Romero, The Violence of Love. Compiled and translated by James R. Brockman, S.J. Farmington, PA: The Plough Publishing House, 1998, 28.)

In doing so, Romero made himself vulnerable to verbal and physical attacks. He didn’t stop speaking the word entrusted to him, and he didn’t hide himself away. He lived among those with whom he was in conflict. He stayed in the struggle and kept reaching out to keep others there. Conflict was, in a sense, his ministry, a component of pastoral care.

“No one wants to have a sore spot touched, and therefore a society with so many sores twitches when someone has the courage to touch it and say: ‘You have to treat that. You have to get rid of that.’” (Romero, 30)

“There is conflict—God be blessed. When a sore spot is touched, there is conflict, there is pain.” (Romero, 26)

Romero’s words about “touching the wounds” suggest a connection to John 20. In a speech on Populorum Progressio two years ago, Cardinal Tagle reflected that it is in touching the wounds of the body of Christ that Thomas came to know fully his Lord and God. God enters into human life and does not leave, even when humans lash out against having their wounds touched. The Body of the risen Lord is marked by human rage and division, and our encounter with it includes drawing very near to that hurt, our hurt that he has taken into himself. Touching the sore points of our shared life is stressful. That is all the more reason to proclaim its relationship to our unity with Christ, to our hope in his faithfulness.

Romero lived in hope that the final word for humanity’s warring against itself and against God is the triumph of mercy. That priority of attention to our destiny allowed him to stand in intense conflict without becoming bitter.

“Blessed are those who feel and live the crisis and who settle it with a commitment to our Lord.” (Romero, 93)

How different Romero’s way is from the habits common in the church in the US! Consider just one example among the many we could observe at all levels. Tuesday, the USCCB approved the new letter that will introduce their statement on voting for 2020. Cardinal Cupich with Bishop McElroy urged the bishops to include in their new letter a full paragraph from Pope Francis’ Gaudete et Exsultate that would situate abortion within the full range of moral matters to be considered. That paragraph reads,

101. The other harmful ideological error is found in those who find suspect the social engagement of others, seeing it as superficial, worldly, secular, materialist, communist or populist. Or they relativize it, as if there are other more important matters, or the only thing that counts is one particular ethical issue or cause that they themselves defend. Our defence [sic] of the innocent unborn, for example, needs to be clear, firm and passionate, for at stake is the dignity of a human life, which is always sacred and demands love for each person, regardless of his or her stage of development. Equally sacred, however, are the lives of the poor, those already born, the destitute, the abandoned and the underprivileged, the vulnerable infirm and elderly exposed to covert euthanasia, the victims of human trafficking, new forms of slavery, and every form of rejection.[84] We cannot uphold an ideal of holiness that would ignore injustice in a world where some revel, spend with abandon and live only for the latest consumer goods, even as others look on from afar, living their entire lives in abject poverty.

The proposal was voted down, and the new letter, according to America’s coverage, will include this statement instead:

“The threat of abortion remains our preeminent priority because it directly attacks life itself because it takes place within the sanctuary of the family and because of the number of lives destroyed,” the letter reads. “At the same time, we cannot dismiss or ignore other serious threats to human life and dignity such as racism, the environmental crisis, poverty and the death penalty.”

Archbishop Chaput insisted that the vote to use “preeminent priority” rather than quoting Gaudete et Exsultate was no indication of conflict with Pope Francis.

“I’m certainly against anyone stating that our saying [abortion is] preeminent is contrary to the teaching of the pope,” he said. “That isn’t true. It sets up an artificial battle between the bishops conference of the United States and the Holy Father, which isn’t true.”

Readers may consider for themselves whether the vote strikes them as evidence of conflict with Pope Francis. I’m more concerned about what this episode clearly is not: it is not straightforwardly engaging the destructive conflict raging within the Church in the US (and within the whole human community and all creation). It is not about frank encounter aimed at healing this Body that is tearing itself apart over federal elections. And so it is not, in spite of claim to be consistent with unity, about the unity of the Body of Christ.

In fact, for some present, the wording was explicitly intended to continue to support the construction of a voting block within the Church. Archbishop Alexander Sample, one of those who advocated for the “preeminent priority” language, is reported to have advocated for it in these terms:

“We are at a unique moment with the upcoming election cycle to make a real challenge to Roe v. Wade, given the possible changes to the Supreme Court,” he wrote. “We should not dilute our efforts to protect the unborn.”

He is referring to, if not explicitly supporting, a utilitarian calculus: voters should be advised that serious Catholics will tolerate any other evil in order to pack the court to change Roe v. Wade. Getting those votes– which in the past has included some parties getting them by misrepresenting Catholic teaching and fomenting mistrust among the faithful — outweighs the need to frankly and fully acknowledge the moral tragedies we face and to enter seriously into the conflicts we have over what to do about it.

The letter that was adopted is likely leave the faithful (those who bother to look at it) once again confused and divided. We will be urged to make ourselves a weapon in the war to end abortion and in so doing, to pay no heed to the wounds in our own Body, “the sacrament of the unity of the human race.” For example, this message does not call us to frank conversation about the constant, pervasive realities of racism and sexism that demean and damage so many in the US and so many in the Church, and which have everything to do with our divisions over party politics and the legal status of abortion. It does not call on us to confront and overcome the stereotypes by which we dismiss each other as uneducated fascists or social justice warriors. It does not call for us to explore our terror and rage at the climate crisis. It does not invite deep reflection on our experiences of gender and sexuality in light of the gospel. It does not give room for sharing our grief and frustration at a US political order that pits the lives of the unborn against the lives of the born. It does not pave a way for what Bishop McElroy described as “difficult and piercing questions or searing dialogues.”

Conflict, as we have come to know it in the US Catholic community, frightens us and beats us down. It also provides an adrenaline rush that makes it hard to break the pattern. Yesterday’s exchanges among the bishops suggest that many of them, like so many of us, are simultaneously maintaining existing battlelines while denying that there is any real conflict among the faithful that needs to be openly engaged. Instead of entering into the risky frank conflict that Romero modeled, they — and we– are staying behind the walls of our bunkers, even if we know they are really prisons. Bishop McElroy’s call for synodality is an invitation for us instead to wade into troubled water.

I need to call my two acquaintances and schedule another dinner. This time I’ll light a candle before an icon of St. Oscar on my way out.