The readings for this Sunday may be found on the USCCB website:

“Do you think something amazing will happen today?” I asked my daughter as she was waiting by the door for the school bus in the early hours of the morning. “I hope so,” she said. It was a playful exchange meant to help pass the time, but it took on a deeper significance in light of this Sunday’s Mass readings, which lead us into this season of waiting for Christ’s birth in Bethlehem. Advent is a season of waiting, but if one were to ask us what we wait for during this time, how certain would be of our answer? In Advent, we wait for something “amazing” to happen, but to what extent do we expect to be amazed when it comes? In one sense, we know what we wait for and when know when it will occur, since after all, the historical event of Christ’s birth lies in the past. How surprised could we really be, how truly amazed? And yet the readings for this Sunday, along with most all the readings during Advent, speak of anticipating what is to some degree unexpected, unpredictable, and even unimaginable.

To wait for something, one needs to know at least something about what one is waiting for. One needs some language or some conceptual framework in which to express what one anticipates. So Israel’s prophets convey their hope in terms of the nation’s covenantal history and the promises associated with it. They imagine the anticipated fulfillment of these promises as emanating from “the mountain of the Lord,” the place where the Lord’s presence is centered within the world. This mountain refers most immediately to Mt. Zion, the site of the Jerusalem Temple, but it also echoes the “holy mountain” where the Lord revealed His name and His Law to Moses. One thinks of the three days in which Israel waited at the bottom of Mt. Sinai for the Lord to appear; they knew they had to be ready, but they did not know how their God would appear or what He would do or say. Likewise, in the days of the first Temple, Isaiah imagines how “in the days to come, the mountain of the Lord’s house shall be established as the highest mountain,” and that “all nations shall stream toward it,” joyfully anticipating that there, at “the house of the God of Jacob,” all people will learn His ways and walk in His paths.

It would have been no surprise to Isaiah’s audience that the Temple would be the place where right relationship will be definitively established with God, but it would have been harder to imagine that this moment of fulfillment would involve more than just Israel, that somehow the Lord would extend His covenantal promises to many peoples. It would have been easy to image how this moment of fulfillment would involve judgment between the nations, but it would have been much harder to fathom that its end would be a universal, lasting peace in which swords would become plowshares and spears pruning hooks.

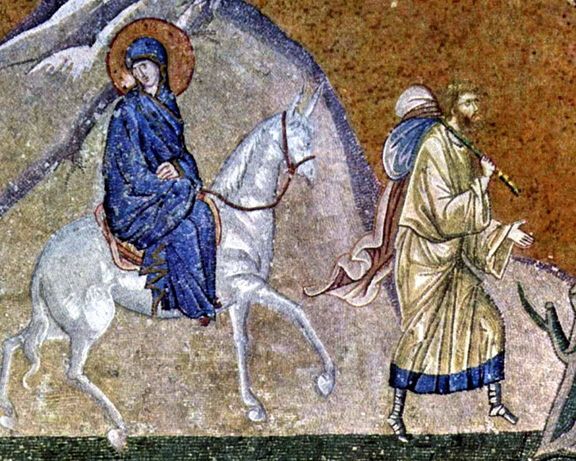

Israel imagined that the fulfillment of their hopes would take the shape of the most important places and signs in the history of their covenantal relationship. Yet there is always something new, something more involved, something unexpected and unimaginable in terms of established categories and patterns. When it finally comes, it will be recognizable, but it will also be amazing; far exceeding what was in the minds of those who anticipated it. For example, although Isaiah affirms that the long-awaited Messiah will come from David’s line, he also suggests that the sign of His coming will be that “the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall call him Emmanuel, ‘God with us’.” The genealogies of Matthew and Luke go to great trouble to show that Jesus comes from David’s bloodline, but ironically they also make it clear that Jesus has no blood relation to the one at the end of that bloodline. Jesus appears in the world as a “son of David,” and yet He is also equally and unpredictably “the son of Mary,” of whose ancestry the gospels make no mention.

Preparing for Christmas can often be a time of busy routine, in which we go through the motions of putting up decorations, sending Christmas cards, baking cookies, and wrapping presents. There is a rhythm to the days leading up to Christ’s birth, and to a great extent that rhythm depends upon the predictability of what will happen and when. To the degree that we focus on the biblical story of Christmas, we do so through scripted pageants and choreographed liturgical readings. We watch the same Christmas movies each year, listen to the same carols, and all too often imagine the events that happened so long ago according to the same mental images. Our answer to the question “what are we waiting for? What are we preparing for?” is one we could give automatically, “in our sleep” as it were.

We can pass through this season of waiting in a kind of stupor, operating “on autopilot” amidst a time where everything is planned out, anticipated, scheduled. Although the season might be “special” in so far as we do special things that are out of the ordinary, the scriptures exhort us to a deeper level of anticipation, requiring a heightened level of attentiveness. When we think we know exactly what we are waiting for, we are no longer prepared to be amazed by what will happen. In the gospel reading, Jesus makes it clear that the defining feature of the moment when the Son of Man comes is that it will shatter our routines. He exhorts his followers to be ready, to stay awake, and to stand guard precisely because something entirely new and unimaginable will break into our predictable lives.

So as we prepare our homes and our hearts for the moment Christ comes among us, we might ask ourselves whether we are leaving room for something to happen in a way and at a time that breaks through our ordered plans and patterns to bring about something entirely new and unimaginable. We should prepare in a way that leaves space for the possibility of sudden and unfathomable amazement.