This is a guest post by Dr. Maureen Day, Assistant Professor of Pastoral Theology at the Franciscan School of Theology in Oceanside, California. Dr. Day is a graduate of the Graduate Theological Union and teaches courses in moral theology and pastoral ministry at the Franciscan School of Theology. Her research focuses on American Catholic civic engagement. She can be reached by email at maureenday@fst.edu.

In “Making Sense of the Numbers,” Beth Haile posted several questions as she looked over the Pew Research Center’s data on the recent election. Here I am going to discuss her final question, to paraphrase: Why are there such political differences between white and Hispanic Catholics and what can be done about it?

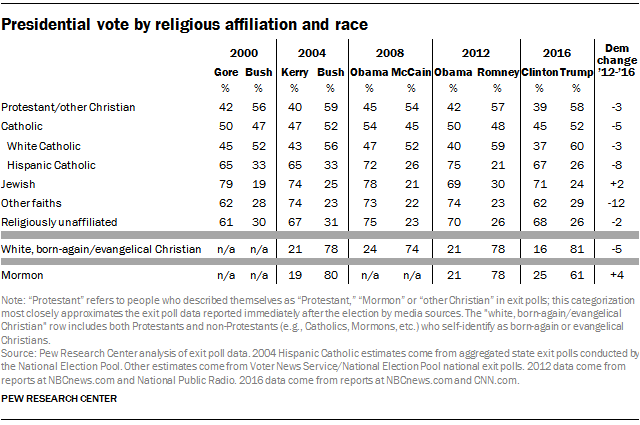

First, why is there this very significant difference? To give this question a broader context, look closely at the chart once more. This time rather than comparing the white and Hispanic Catholics, as I will for most of this posting, compare the white Catholics with their demographic cousins, “Protestant/other Christians” (this excludes those who identify as born-again/evangelical and are counted separately). These are often called “mainline Protestants” and include groups like Lutherans, Methodists and Episcopalians. They are demographically similar to Catholics when you compare them on a host of factors, such as family size, income and education level. Here we see that 39 percent of non-evangelical Protestants voted for Clinton and 58 percent voted for Trump. This is nearly identical to the white Catholic vote in which 37 percent voted for Clinton and 60 percent voted for Trump. What does this tell us? This tells us that – as Jason King put it succinctly in “A Catholic Vote?” – white Catholics are voting like white Americans of their respective demographics and there is little statistical evidence indicating that their vote is distinctively Catholic. This change happened gradually, perhaps over the last two generations (see Christian Smith and team’s Young Catholic America). Likewise, the chart shows that this mirroring of mainline Protestant and white Catholic religious attitudes have persisted for several election cycles. This is not to say that there are not many white Catholics who seriously pray and struggle over these issues and look at the candidates with Catholic eyes. But these are the exceptions to the rule and the percentage of highly-committed Catholics has been decreasing among American Catholics, from 27 percent in 1987 to only 19 percent in 2011, according to D’Antonio and colleagues’ most recent survey.

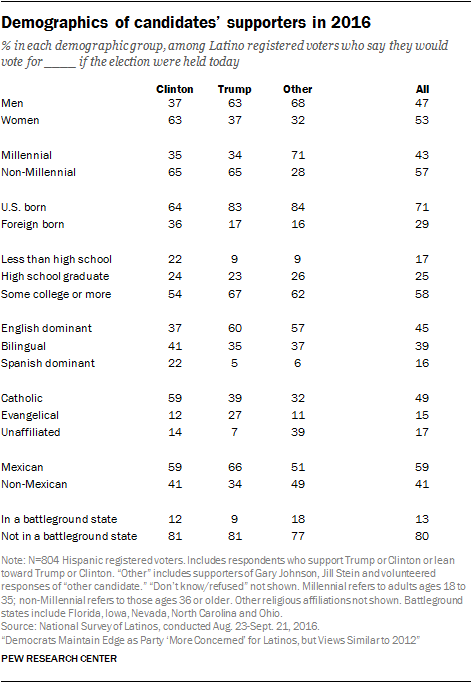

The Latino vote tells a different story. Looking at more data from Pew, we see that the Latino vote is strongly influenced by religion. This data is a bit cumbersome as it first divides people according to who they would vote for and then breaks that group up further according to religious affiliation, but it illustrates that religion has a clear impact on Latino voting, with Latino Catholics more likely to support Clinton and evangelical Latinos overrepresented among Trump supporters. Before I get hounded about comparing Latino Catholics to evangelicals when I compared Catholics to mainline Protestants among white voters, it is important to note that (according to yet more Pew data) only five percent of Latinos identify as mainline Protestants. Nearly half identify as Catholic, nineteen percent as evangelical, twenty percent are unaffiliated and no other religious group breaks two percent. All this to say that when we examine religious motivations underlying the Latino vote, Catholics and evangelicals are the statistically better comparison.

To summarize the above, white Catholics generally vote according to their demographic situation, with religion playing little, if any, role. The data on Latino Catholics shows the opposite, with faith measurably affecting the way they vote.

And the Latino vote is crucial for understanding the Catholic vote now and in the future. First, the importance of now: It is not that Latinos are more progressive; they are simply more orthodox. It will come as no surprise to readers of this blog that the platforms of the Republican and Democratic parties do not encompass the whole of Catholic social teaching. To vote as American Catholics requires us to give serious thought to the issues of the day – poverty, euthanasia, climate change, abortion, immigration, war – and consider which candidate’s policies will best bring the Gospel to fruition. According to the D’Antonio team’s study referenced above, Latino Catholics are more strict on who can be counted as a “good Catholic” than white Catholics and they are consistent in applying these tighter boundaries to both progressive and conservative issues. For example, fewer believe that one can be a good Catholic while ignoring Church teaching on abortion (47% of Latinos compared to 65% of non-Latino, the latter of which are overwhelmingly white) and fewer would call someone a good Catholic if they went against the Church teaching prohibiting divorce and remarriage (56% vs. 75%). Likewise, more Latino Catholics than non-Latino Catholics find it necessary to help the poor to be a good Catholic (52% vs. 64%). Latino Catholics are more orthodox on these political issues as well as theological doctrines, such as transubstantiation. American politics is messy for a Catholic. The data on Latino Catholics indicates that Latino Catholics are more enmeshed in Catholicism in both their beliefs and their voting. Learning the ways they weigh these issues to formulate a Catholic response in the voting booth would be illuminating for the American Church. The simple answer to “Why is there such a large gap between Latino and white Catholics?” is that white Catholics are more likely to reflect the politics of their race, education level, geographic region and other demographic indicators than the teaching of their faith. Latino Catholics appear to integrate religion more fully into their moral decisions and show significant moral differences when compared to their evangelical counterparts. They also are more able to get out of the Republican/Democrat binary that seems to define politics for white Catholics.

The Latino vote is also crucial for the future for two reasons. First, Latinos are turning out in greater numbers with every presidential election, with an estimated 14 million ballots cast this election compared to the 11.2 million in 2012 (yes, rates of eligible voter turnout among Latinos are still low, but they will have increasingly more influence due to their relatively faster population growth). Second, the proportion of white Catholics are shrinking as the Latino share increases. While only two percent of Catholics over seventy years in 2011 were of Hispanic origin (compared to the 96 percent of this age group who identified as white), 23 percent of those between the ages of 51 and 70 did so. Further, 40 percent of Catholics between 32 and 50 years old are Latino as are 45 percent of Millennial Catholics. With these demographic shifts, it will not be long before the Latino vote more directly determines the Catholic vote. I hope that the Catholic orthodoxy of Latino Catholics and the large voting bloc they seem destined to be will shape the very contours of the two parties, forcing Republicans and Democrats alike to rethink the policies that are at odds with Catholic moral theology.

Finally, what can be done to close the gap? If we are looking for a quick and easy solution, not much. Although these groups sometimes share a parish, they are often separated into different worship communities. The wider world does not do much to bring these two groups together, either. With an aging population of white Catholics and Latinos filling the once-empty pews, there is too often a sense that “they” (Latino Catholics) are “taking over.” I have read this in sociological interview data and heard this on Catholic radio (the radio host politely informed the caller that he was half Hispanic). Sure, there are brilliant examples of intercultural worship, but we must be honest that these are exceptions. Without intentional and facilitated bridging, the two worlds that Latino and white Catholics inhabit will remain fairly separate.

That is the thing, it is possible. But it will take work.

The difference between Latino and white Catholics’ votes is not a problem in itself. Rather, it is a symptom of a larger problem of a disconnect with one another. Pope Francis’ twitter handle is Pontifex: bridge-builder. He himself comes from a mingling of the European and Latino worlds and his bringing people together in a spirit of friendship and hospitality offers a model for the American Church. Too often the American Church has not welcomed ethnic groups. There was hostility toward the Irish from the French priests. Then once the Irish established themselves, they ridiculed the traditions of the Italians and Polish. Black Catholics were literally turned away at parish doors. This list of exclusion is not exhaustive and now Latinos are experiencing this. As is often the case with dominant and subordinate groups, white Catholics do not know the reality of Latino Catholics as well as Latino Catholics know the dominant culture. If past research is any indicator, personal, lasting relationships are the surest way to open the eyes of one group to the experiences of another. A pressing challenge for the American Church is to bridge the chasms among the faithful in a spirit of humility and charity.

Subsidiarity indicates that this is a task best handled at the parish level. Advent – featuring our mother Mary so prominently – provides a time of joy and anticipation to recall what unites us, to reach out to those who truly are our sisters and brothers. Again, it will not be easy and every parish will face its own challenges, but care and intentionality can help us to see the American political world through the Catholic imagination.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks