Solomon Northup woke up in chains. This was only the beginning.

Then did the idea begin to break upon my mind, at first dim and confused, that I had been kidnapped. But that I thought was incredible. There must have been some misapprehension—some unfortunate mistake. It could not be that a free citizen of New York, who had wronged no man, nor violated any law, should be dealt with this inhumanly. The more I contemplated my situation, however, the more I became confirmed in my suspicions. It was a desolate thought, indeed. I felt there was no trust or mercy in unfeeling man; and commending myself to the God of the oppressed, bowed my head upon my fettered hands, and wept most bitterly. [Solomon Northup, Twelve Years A Slave, 17.]

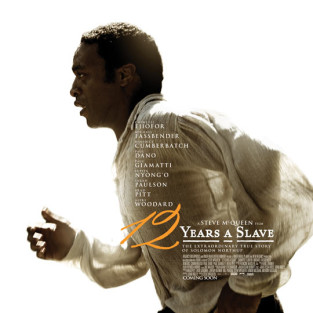

Twelve Years A Slave is a powerful film based on the book by Solomon Northup, in which he recounts his experiences as a slave in Bayou Boeuf, Louisiana. Published in 1853, the book was a best-seller. Solomon Northup’s life story is unusual, in that he was educated and lived until his early adult life as a free man. Living in Saratoga, New York, with his wife and children, he lived the life of a free man, aware of the plight of slaves but without first-hand knowledge of the trauma they endured daily. All of that changed when he was kidnapped and sold into slavery himself, spending twelve long years as a slave in Louisiana. He later had the opportunity to share his story in a quest to abolish the institution of slavery.

The film will make you wonder how people can be so cruel, especially white people who claimed to be Christian, and if you are white, this will be uncomfortable. That is exactly why Christians should watch this film. This film makes the viewer confront the cruelty of slavery: commerce in human bodies, splitting of families, torture, rape, humiliation, mental anguish. It is well-acted and heart-wrenching. It is a tough film to watch. You may find that you agree with Solomon when he writes that “there was no trust or mercy in unfeeling man.” You may hope for a happy ending and sense of justice in the conclusion. But you will realize that the ugly truth of slavery is that justice in this world is incomplete, provisional, and imbalanced. Because the truth is that we continue to live in a racist world, a world marked by extreme income inequalities, a world where human trafficking is real. So yes, this is part of American history, but it is also part of America’s present. And this hurts. It should. If you go see this film on date night with your spouse, you might find that it is hard to talk about anything afterwards because everything feels trivial in comparison to the horrors you just witnessed on the big screen. This is as it should be. This film is not a feel-good holiday movie. This film is not a comedy. But the world would be a better place if more films like this were made—and watched. Film critic Wesley Morris suggests: “The power of [Director Steve] McQueen’s movie is in its declaratory style: This happened. That is all, and that is everything.” I couldn’t agree more.

If afterwards you are hungry for some readings to delve into the theo-ethical problems that Christians confront in and through this story, I humbly suggest the following: anything written by James Cone, M. Shawn Copeland, Bryan Massingale, Emilie Townes, or Diana Hayes. OK, let me try to be more specific.

Theology of God in the Face of Suffering: Cone and Black Liberation Theology

Solomon Northup (played by Chiwetel Ejiofor) commends himself to the “God of the oppressed.” This is the title of James Cone’s powerful book that constructs a theology of Black liberation in the face of oppression. I would describe this as a “classic text,” a must read for all theologians and ethicists. Together with his first book, A Black Theology of Liberation, Cone’s God of the Oppressed is intentionally provocative, challenging basic assumptions about theological anthropology and Christology. Cone was born in 1938 and is a beloved teacher at Union Theological Seminary in New York City.

For Cone, the central message of Christianity is one of liberation. In A Black Theology of Liberation, Cone writes:

The function of theology is that of analyzing the meaning of that liberation for the oppressed community so they can know that their struggle for political, social, and economic justice is consistent with the gospel of Jesus Christ. Any message that is not related to the liberation of the poor in society is not Christ’s message. (358).

Cone condemns “white theology”– theology that has sanctioned oppression and empowered Whites over Blacks. Examples are abundant in Twelve Years A Slave: for example, when Master Epps uses the Bible to harrass and terrorize the people he owns as property. Cone argues that White theology is not authentic theology; it is a “theology of the Antichrist.”

Black Theology is a theology of liberation because it is a theology which arises from an identification with the oppressed blacks of America, seeking to interpret the gospel of Christ in the light of the black condition. It believes that the liberation of black people is God’s liberation. (Cone, 359)

Cone helps us to think about the plight of Solomon as Cone identifies Jesus as the “Black Christ.” Christ took on the suffering of others and became the Oppressed One in order to bring redemption.

Is the work of Christ synonymous with the work of the oppressed or the oppressors, blacks or whites? Is he to be found among the wretched or among the rich? … Christ must be where men are enslaved. To speak of him is to speak of the liberation of the oppressed. In a society that defines blackness as evil and whiteness as good, the theological significance of Jesus is found in the possibility of human liberation through blackness. Jesus is the Black Christ. (361-362).

When we see Solomon whipped, tortured, humiliated: do we see anew the agony of Christ? When watching this film, it seems crystal clear that the cross of Christ is understood most deeply by the enslaved peoples, not their masters who can read aloud the gospel narratives but by the people whose own scars witness their understanding. And does it make you wonder, dear reader, about how little you understand the cross of Christ, as you sit in a movie theater with popcorn crumbs on your lap? And does it make you angry when you hear television news anchors argue that Santa Claus is white because Jesus was white? Do you worship a white God in a community of white people? If so, Cone presents a challenge: God is not color blind. Cone argues that we live in a racist society, and to say that God is color blind in a racist society means that God is blind to injustice. The Biblical roots of Black Theology recognize that God takes sides: God sides with the Israelites against the Canaanites; God sides with Israel against political oppressors; Jesus takes the side of the poor and unwanted in his society. God is not a neutral observer. So who’s side are you on? Are you on Solomon’s side, or Epp’s?

This is not to say that one must freely choose suffering and humiliation in order to be on God’s side. God desires the liberation of God’s people, not their enslavement. But bringing that liberation is not only the work of God, it is the work of humans who cooperate with God. Solomon Northup tells us, “I do not want to survive. I want to live.” And that’s what God wants too.

The Suffering of Black Women and the Cross of Christ

But Twelve Years A Slave is not only about Solomon. It is also about the other slaves who labored and suffered with him. Patsey (in a haunting performance by Lupita Nyong’o) is a young woman enslaved in the home of Master Epps (Michael Fassbender). Like other female slaves, she endured sexual abuse at the hand of her white master, and because of that she also endured physical and emotional abuse at the hand of her white mistress, Mary Epps (Sarah Paulson). In writing about the Black women’s experiences of suffering in chattel slavery, theologian M. Shawn Copeland recounts the suffering of Harriet Ann Jacobs [who wrote under the pseudonym Linda Brent in her personal story, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl]. Patsey’s story in Twelve Years A Slave is eerily similar to Harriet’s. One may recognize in Harriet Ann Jacobs’ account of her mistress, Mrs. Flint, a striking similarity to Mrs. Epps in Twelve Years A Slave:

Mrs. Flint, like many southern women, was totally deficient in energy. She had not the strength to superintend her household affairs; but her nerves were so strong, that she could sit in her easy chair and see a woman whipped, till the blood trickled from every stroke of the lash. She was a member of the church; but partaking of the Lord’s supper did not seem to put her in a Christian frame of mind. If dinner was not served at the exact time on that particular Sunday, she would station herself in the kitchen, and wait till it was dished, and then spit in all the kettles and pans that had been used for cooking. She did this to prevent the cook and her children from eking out their meager fare with the remains of the gravy and other scrapings. … The mistress, who ought to protect the helpless victim, has no other feelings towards her but those of jealousy and rage. The degradations, the wrongs, the vices, that grow out of slavery, are more than I can describe. [Kindle location 155, 383.]

Harriet Ann Jacobs describes other cruelties:

When I had been in the family a few weeks, one of the plantation slaves was brought to town, by order of his master. It was near night when he arrived, and Dr. Flint ordered him to be taken to the work house, and tied up to the joist, so that his feet would just escape the ground. In that situation he was to wait till the doctor had taken his tea. I shall never forget that night. Never before, in my life, had I heard hundreds of blows fall, in succession, on a human being. His piteous groans, and his “O pray don’t, massa,” rang in my ear for months afterwards. There were many conjectures as to the cause of this terrible punishment. Some said master accused him of stealing corn; others said the slave had quarreled with his wife, in presence of the overseer, and had accused his master of being the father of her child. They were both black, and the child was very fair.

I went into the work house next morning, and saw the cowhide still wet with blood, and the boards all covered with gore. The poor man lived, and continued to quarrel with his wife. A few months afterwards Dr. Flint handed them both over to a slave-trader. The guilty man put their value into his pocket, and had the satisfaction of knowing that they were out of sight and hearing. When the mother was delivered into the trader’s hands, she said, “You promised to treat me well.” To which Dr. Flint replied, “You have let your tongue run too far; damn you!” She had forgotten that it was a crime for a slave to tell who was the father of her child. [Kindle location 171]

When Copeland analyzes Jacobs’ narrative and the other narratives of enslaved women, she recognizes the “maldistribution, negative quality, enormity, and transgenerational character of the suffering of Black women.” [“Wading Through Many Sorrows,” 137.] Copeland writes:

African Americans have encountered monstrous evil in chattel slavery and its legacy of virulent institutionalized racism and have been subjected to unspeakable physical, psychological, social, moral, and religious affliction and suffering. Yet, from the anguish of our people rose distinctive religious expression, exquisite music and song, powerful rhetoric and literature, practical invention and creative art. If slavery was the greatest evil, freedom was the greatest good and women and men struggled, suffered, sacrificed, and endured much to attain it. [137].

Drawing on slave narratives, Copeland develops a womanist theology of suffering, taking seriously the experiences of enslaved women and their “collective struggle to grasp and manage, rather than be managed by, their suffering” [139] Drawing on the life stories of Harriet Jacobs, Mary Prince, Louisa Picquet, Mattie Jackson, and others, Copeland argues that the evil of chattel slavery involved the “full and arrogant self-assertion of white male power and privilege, white female ambivalence and hatred, the subjugation of Black women and men.” And yet, in Copeland’s analysis:

These are narratives of affliction, but not narratives of despair; the women may be caught, but they are not trapped. These Black women wade through their sorrows, managing their suffering, rather than being managed by it. [148].

In Copeland’s reading, these women are agents (not pure victims) in constrained circumstances of real and overwhelming structural violence. Copeland recounts examples of enslaved people resisting oppression in a variety of ways, including the singing of spirituals and even the use of sass or back-talk to stand up for one’s own dignity. [150-153]. The spirituals recovered the stories of liberation through lyrics such as “Let My People Go,” “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” and “O My Lord Delivered Daniel, O Why Not Deliver Me Too?” Copeland, like Cone, sees the Christological implications of these hymns and the identification with the suffering of Jesus:

If the makers of the spirituals gloried in singing of the cross of Jesus, it was not because they were masochistic and enjoyed suffering. Rather, the enslaved Africans sang because they saw on the rugged wooden planks One who had endured what was their daily portion. The cross was treasured because it enthroned the One who went all the way with them and for them. The enslaved Africans sang because they saw the result of the cross–triumph over the principalities and powers of death, triumph over evil in this world [150].

Still, these forms of resistance were not without danger. And in reading Jacobs’ life story, one encounters women who have every reason to despair. In one episode, Jacobs’ explains that New Year’s Day is a time of great anxiety for slave mothers because the next day is the biggest slave trading day of the year.

She sits on her cold cabin floor, watching the children who may all be torn from her the next morning; and often does she wish that she and they might die before the day dawns. She may be an ignorant creature, degraded by the system that has brutalized her from childhood; but she has a mother’s instincts, and is capable of feeling a mother’s agonies.

Jacobs explains one such woman’s story: All seven of her children were sold on the same day:

She wrung her hands in anguish, and exclaimed, “Gone! All gone! Why don’t God kill me?” I had no words wherewith to comfort her. Instances of this kind are of daily, yea, of hourly occurrence. [Kindle location 211]

Jacobs had no way to comfort this grieving mother. Copeland invites us to think critically about any attempt to offer comfort or easy analysis of the complexity of suffering:

A theology of suffering in womanist perspective repels every tendency toward any ersatz spiritualization of evil and suffering, of pain and oppression… A theology of suffering in womanist perspective remembers and retells the lives and sufferings of those who “came through” and those who have “gone on to glory land.” This remembering honors the sufferings of the ancestors, known and unknown, victims of chattel slavery and its living legacy. [155]

Where is the Catholic Church?: Ecclesiological Dimensions of Slavery

Pope Leo XIII, in an 1890 pastoral letter addressed to the bishops of the whole world, claimed:

Many of our predecessors, including St. Gregory the Great, Hadrian I, Alexander III, Innocent III, Gregory IX, Pius II, Leo X, Paul III, Urban VIII, Benedict XIV, Pius VII, and Gregory XVI, made every effort to ensure that the institution of slavery should be abolished where it existed and that its roots should not revive where it had been destroyed.

Historian John Francis Maxwell writes:

With the greatest respect to Pope Leo XIII, this is historically inaccurate… All these twelve popes, who are given special commendation, had only condemned what they and contemporary moral theology held to be unjust methods of enslavement or unjust titles of slave ownership. Five of the popes mentioned were the authors of other public documents that actually authorized enslavement as an institution, as a penalty for ecclesiastical crimes, or as a consequence of war.

Diana Hayes, in a review essay on slavery, explains the complicity of Christians (and of the institutional church) in the moral evil of slavery:

For centuries, the church saw slavery as a feature of the natural law: some people were meant to be slaves, while others were meant to be their masters. [72]

Pope Gregory I (circa 600) provides but one example of this theological justification of slavery:

A hidden dispensation of providence has arranged a hierarchy of merit and rulership, in that the difference between classes of men has arisen as a result of sin and is ordered by divine justice. [73]

Hayes draws on the teaching of Jesus of Nazareth to pose this theological problem:

In his first sermon, Jesus proclaimed the realization of Isaiah’s prophecy that one would come who would proclaim “good news to the poor… release to the captives [and that] the oppressed [would] go free” (Luke 4:18). It is ironic indeed that a church founded on such principles would become the legitimizer of a form of slavery that dehumanized native and African peoples and established a mindset that differentiated people on the basis of race. This consciousness fostered the rise of racism, an ideology that haunts humanity, especially in the United States, to the present day, both in and outside the church, as the U.S. bishops acknowledged in their 1974 pastoral letter on racism, Brothers and Sisters to Us.

As Maxwell notes, Leo XIII’s assertion that the church always opposed slavery is sadly inaccurate. Before the end of the slave trade in the nineteenth century, with few exceptions, the Roman Catholic Church did support and maintain with all its power, secular and spiritual, the enslavement not only of non-Catholics but of its own Catholic faithful. [73-74]

John T. Noonan, Jr. has also written extensively on the development of doctrine, using slavery as a test case. While we have textual evidence that St. Paul accepted slavery, so too did St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas. The first perceptible change occurred when in 1839 Gregory XVI condemned the slave trade; despite this the Holy Office ruled in 1866 that the buying and selling of slaves was not contrary to the natural law as long as slaves were treated in a humane way. Only after the cultures and laws of Europe and America changed through the abolitionists’ agency did Catholic doctrine begin to repudiate slavery as immoral–and in doing so, the popes drew on scripture and tradition to make their case. But as Diana Hayes reminds us, they had also drawn on scripture and tradition to argue in favor of slavery before that. Hayes argues there is a right and wrong answer here:

The interpretation of scripture and tradition by which the church supported [slavery] was a product of the times and the conditions of society during those times. Nonetheless, this interpretation was immoral then and still is today. [74-75]

An ecclesiological problem that remains is that it took the church a long time to realize slavery was incompatible with morality. Why this moral blindness? Where was the Holy Spirit? The methodological problem that remains is this: we continue to draw on the same sources, but we draw different conclusions. How do we determine the “legitimate” argument in the face of these competing narratives? Ultimately, in my view, it was the data of human experience: both “outside” voices in abolitionist culture, and “inside” voices of enslaved peoples, whose narratives spurred the consciences of the people who called themselves Christian. This raises all kinds of ecclesiological and methodological questions for ethics today. Bryan Massingale has tackled some of these head-on in his book, Racial Justice and the Catholic Church, a book I highly recommend even though I can only name some of his conclusions here. Massingale argues that the Catholic Church has not adequately addressed racism, but that we do have the resources in place to do so. He writes:

Faith communities are called to be communities of conscience, that is, places where the truth is spoken about how our culture has both formed and malformed our personal identities to the detriment of our public life together. Situating our ethical strivings for racial justice in a counternarrative–in an alternative set of meaning and value–is an indispensable contribution that a religious faith makes to the goal of achieving a more racially just society. (126).

Solidarity Today: The Praxis of Christianity

In her recent book, Dr. Shawn Copeland writes of the praxis of solidarity:

Solidarity presents a discernable structure with cognitive, affective, constitutive, and communicative dimensions. Through a praxis of solidarity, we not only apprehend and are moved by the suffering of the other, we confront and address its oppressive cause and shoulder the other’s suffering. Orienting ourselves before the cross of the crucified Christ, we not only attempt to realize ourselves as the mystical body, but intersubjectively, linguistically, practically, prayerfully to communicate who we are, and for what and for whom we struggle. Solidarity sets the dynamics of love against the dynamics of domination. (Enfleshing Freedom, 94).

Solidarity requires that Christians accompany suffering people, understanding the depths of their pain and their strategies for resisting it. Solidarity is an invitation to listen, to walk with, to struggle with the suffering person. But it involves risk. You may be moved to tears. You may have to see the world differently. You may recognize your own complicity in the sufferings of others. You may have to think in a new way about what you take for granted. It will make you uncomfortable, at least at first. But stick with it, because this is how you will be saved. It is a process, of course. But one way to enter into the pain of another’s life is to watch films that challenge you. This is one of those films.

I think Harriet Ann Jacobs would express gratitude to director Steve McQueen and screenwriter John Ridley, as well as to all of the actors in this film, who bring to life the misery and evil of chattel slavery for a modern audience. To silence the victims of violence—in our past or in our present—is to do an injustice because it feeds denial and moral blindness. I hear in Jacobs’ own narrative a blessing on the filmmakers who make us wrestle with the reality of slavery and its modern day manifestations:

Why are ye silent, ye free men and women of the north? Why do your tongues falter in maintenance of the right? Would that I had more ability! But my heart is so full, and my pen is so weak! There are noble men and women who plead for us, striving to help those who cannot help themselves. God bless them! God give them the strength and courage to go on! God bless those everywhere who are laboring to advance the cause of humanity! [Kindle location 418]

Sources and Suggestions for Further Reading:

A Troubling in My Soul: Womanist Perspectives on Evil and Suffering, ed. Emilie Townes (Maryknoll: Orbis, 2003).

James H. Cone, from A Black Theology of Liberation, in Wogaman and Strong, eds., Readings in Christian Ethics; see also Cone, God of the Oppressed (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1975)

M. Shawn Copeland, “Wading Through Many Sorrows,” in Feminist Ethics and the Catholic Moral Tradition, eds. Curran, Farley, & McCormick (1996), reprinted in the new reader Womanist Theological Ethics: A Reader, eds. Cannon, Townes, and Sims (2011).

M. Shawn Copeland, Enfleshing Freedom: Body, Race, and Being (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2010).

Diana Hayes, “Reflections on Slavery” in Rome Has Spoken, ed. Fiedler and Rabben (New York: Crossroad, 1998), reprinted in Readings in Moral Theology; see also And Still We Rise: An Introduction to Black Liberation Theology (New York: Paulist, 1996).

Harriet Ann Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (Kindle Edition)

Bryan N. Massingale, Racial Justice and the Catholic Church (Maryknoll: Orbis, 2010).

John T. Noonan, Jr. “Development in Moral Doctrine.” Theological Studies 54 (1993): 662-677; See also, A Church That Can and Cannot Change: The Development of Catholic Moral Theology (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2005).

Film Reviews:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/kia-makarechi/12-years-a-slave_b_4174374.html

http://www.grantland.com/story/_/id/9870721/the-cultural-crater-12-years-slave

Thanks for this excellent post.

The sad reality is that the Catholic Church has been rather complicit in slavery. Popes and religious orders owned slaves, slavery was legal in the papal states, a number of US Bishops owned slaves in 1860 and taught that slavery was OK. Not to mention all those Catholic schools which were once segregated and the sad fact that our first black U.S. priest had to be trained in Rome as no U.S. seminary would have him.

I sometimes wonder what things the Church is wrong about today which will become apparent in future years. I expect that the way we have mistreated our gay and lesbian brothers and sisters will be one of them.

God Bless