On Mondays throughout the year, New Wine New Wineskins, a fellowship of early-career moral theologians, shares posts from members. This week, Antônio Lemos shares from his dissertation research on the ethics of migration and property. For more information about the upcoming 2024 NWNW annual conference, held this July at the University of Notre Dame, and how to submit a proposal, see the Call for Papers here. And, as always, check back each Monday for more content from New Wine New Wineskins!

The origin, limits, and function of private property is a key theme in Catholic social teaching. The Second Vatican Council goes back to the fathers of the Church when dealing with the issue of private property and justice, as we can see in Gaudium et Spes n. 69. The key principle to understand the Christian approach to wealth is the universal destination of earth’s goods. By this principle, the Church believes that God created the world for the flourishing of all human beings. Private property should serve this original principle.

This last year, as part of my dissertation research on the right to migrate, I’ve been examining the theological foundations of this principle in the Church fathers. I read them in their historical and textual context with the view to identify underlying principles and apply them to our present reality, especially the doctrine of the Church on migration ethics. Some of the questions that I tried to address are: what is the origin of private property? Is private property a result of God’s will or a human convention? Is there a good function of property? Are there limits to it? Are there responsibilities towards the poor and the community in general in regard to one’s property?

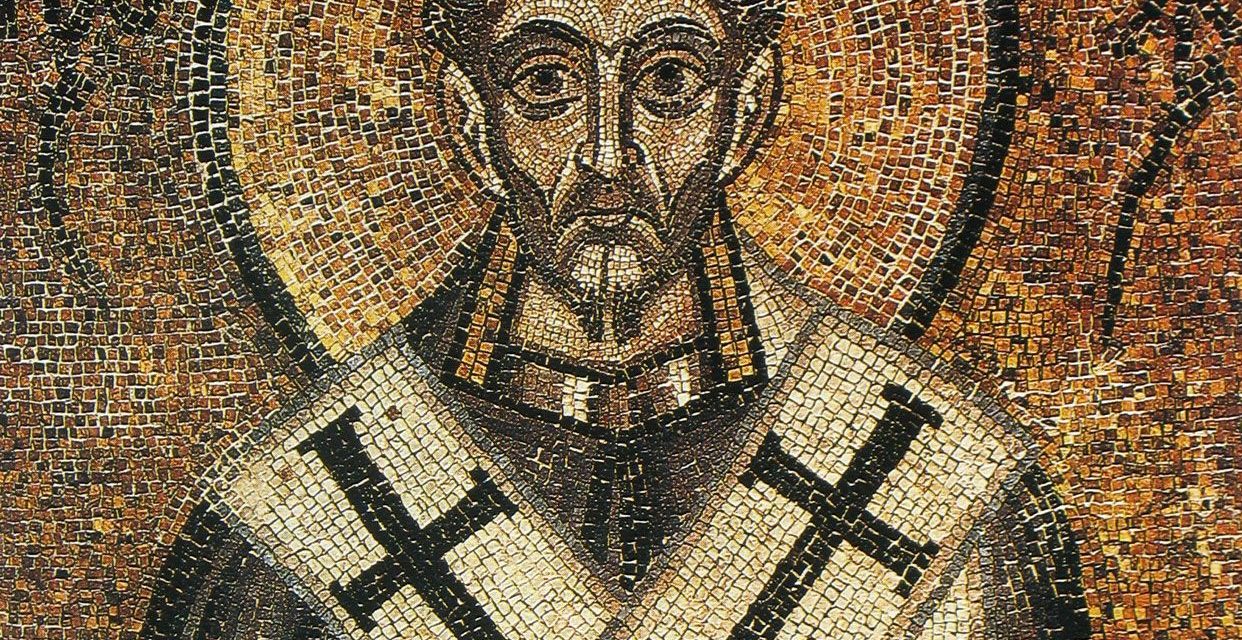

One of the church fathers who has more insightful writings on these questions is St. John Chrysostom (347-407), patriarch of Constantinople. I was surprised by the radicality of his teachings. Here you have a summary of some of my findings that are located in his homilies on the First Letter to the Corinthians and the First Letter to Timothy. We can imagine him preaching about such things in front of an audience of wealthy Christians of the imperial court.

Chrysostom posits that originally, the earth and its resources were intended for common use. Inequality and poverty, according to him, are consequences of evil, and wealth becomes morally acceptable only when used for the common good. Moreover, he emphasizes the idea that everything ultimately belongs to God, and as brothers and sisters of the same lineage, individuals should share their resources equitably. True ownership, he argues, arises when possessions are used to benefit the needy, creating a paradoxical relationship between ownership and altruism. Furthermore, he boldly asserts that God entrusts the wealth of the poor to the wealthy for administration, irrespective of how the wealthy acquired their resources.

One of the most radical ideas from Chrysostom is his take on the ethical responsibilities associated with wealth. He compares the rich to road robbers if they fail to use their resources to help others, and considers neglecting the poor as a form of homicide. Importantly, he distinguishes between wealth itself and the misuse of goods, asserting that wealth, when utilized for the common good, is not inherently evil.

Another challenging teaching by Chrysostom is his concept of ownership. Again he argues that whatever the rich possess, whether inherited or earned through work, ultimately belongs to the Lord and is meant to be shared with the poor. Referring to Mal 3:10 and Eccl 4:1, he contends that the surplus of the rich should not be spent on superfluous things but should be directed towards those in need. He emphasizes that individuals are mere custodians of possessions, not true owners, as everything passes to others upon death.

Finally, the notion of the common good permeates Chrysostom’s teachings. He asserts that everyone contributes to the common good through their work, highlighting the interconnectedness of human existence. Moreover, he finds merit in poverty, suggesting that it can lead one to spiritual elevation and ultimately to heaven.

In conclusion, St. John Chrysostom’s theological reflections on wealth and poverty provide a compelling and challenging framework for understanding the ethical dimensions of private property and the use of material goods. His radical emphasis on the common good, equitable distribution, and the moral responsibility of the wealthy offers valuable insights that resonate with the principles of Catholic social teaching, especially solidarity and the universal destinations of earth’s goods. He does not condemn the possession of wealth, but its misuse.

As contemporary discussions on wealth inequality and social justice continue, Chrysostom’s teachings remain a relevant source of ethical guidance for individuals and societies alike.

Antônio Lemos is a Ph.D. Candidate in Moral Theology at the University of Notre Dame.