written by Kathryn Getek Soltis

originally published February 5, 2015

Job 7:1-4, 6-7 / Psalm 147:1-6 / 1 Corinthians 9:16-19, 22-23 / Mark 1:29-39

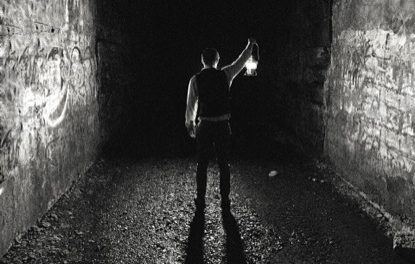

A man detained in a local jail once shared with me something that he feared to reveal to anyone in the facility. His previous HIV positive status had become AIDS. He didn’t even use those words explicitly, but the meaning of what he confided was clear. As the conversation continued, I became more aware of and intentional about making contact with him. Prison volunteers in this facility are instructed to carefully limit contact to handshakes. Touch is a minefield of danger, seduction, and inappropriate boundaries. To be sure, there were many things fueling his fear of how others would treat him. It was not primarily the deprivation of touch since this is a basic fact of life for that environment, HIV/AIDS or not. Yet, in that moment of his revelation, touch became an instinctual strategy for how to communicate some sense of compassion, how to express recognition in the midst of so many layers of alienation.

This is the encounter that first came to mind when reading the Gospel for this coming Sunday. In the passage from the opening chapter of Mark, we find Jesus in the house of Simon and Andrew, tending to Simon’s mother-in-law who is sick with a fever. Jesus goes on to cure many who are ailing or possessed and then sets off for other villages to preach and drive out demons. But the image that stayed with me was back with Simon’s mother-in-law. Jesus “approached, grasped her hand, and helped her up.” This detail of the grasping of her hand is one I have passed over many times before without much thought. Yet, its inclusion is significant. It is not simply the fact that a healing took place, but the manner in which it occurred. So often in the New Testament, Jesus heals through touch (e.g., the man born blind and Jairus’ daughter). While other senses are highlighted in Scripture (all who have ears, listen!), the import of the tactile sense must not be overlooked. Indeed, Thomas may have believed because he had seen, but he also demanded to touch the wounds – and this is exactly what Jesus invited him to do.

Yet, for all its import, we hear very little about our moral responsibilities as Christians vis-à-vis the sense of touch. The abusive, destructive touches which have been perpetrated in the Church and through its complicity certainly give us reason to be suspicious. Touch is not always good. And its meaning is contextually conditioned, especially by culture and gender. Given it various connotations and potentialities, we are understandably skittish when it comes to skin-to-skin contact. Yet, there is a threshold below which we can say unequivocally that lack of touch is bad. For example, as science journalist Emily Anthes explains in a recent book review:

Babies who are deprived of human touch, such as those who spend their early years in understaffed orphanages, display profound abnormalities. Their growth is stunted, and they’re slow to gain cognitive and motor skills. They display repetitive, self-soothing behaviors, such as rocking endlessly back and forth. They are more likely to develop obesity, diabetes and heart disease, or suffer from mental illnesses ranging from depression to psychosis. But the smallest of interventions — as little as 20 minutes of gentle physical contact a day — can help touch-deprived infants avoid the worst outcomes.

Christian ethicist Christina Traina has compellingly argued that there are rights to touch in her essay, “Touch on Trial: Power and the Right to Physical Affection.” Given the empirically established connections that touch has to growth, development, and health (despite variations in cultural, familial, and other contexts), certain moral obligations can and should be attached to each person’s access to touch. Of course, positive rights are a bit tricky; it is not always readily apparent by whom and by what specific means the responsibilities are to be fulfilled. Moreover, the language of rights tends to direct our attention to the minimum obligations that are due to others. To her credit, Traina’s presentation points beyond minimal thresholds, but I am still left to wonder what other language in addition to rights might be necessary for our society to regard touch as an essential means to communicate compassion, healing, and even social recognition.

The research indicating the power of touch is quite stunning. It suggests that touch is integral to human flourishing, healing, and perhaps even solidarity. Below are just a few excerpts from a 2010 article noting recent studies on touch:

A review of research, conducted by Tiffany Field, a leader in the field of touch, found that preterm newborns who received just three 15-minute sessions of touch therapy each day for 5-10 days gained 47 percent more weight than premature infants who’d received standard medical treatment.

In a study by Jim Coan and Richard Davidson, participants laying in an fMRI brain scanner, anticipating a painful blast of white noise, showed heightened brain activity in regions associated with threat and stress. But participants whose romantic partner stroked their arm while they waited didn’t show this reaction at all. Touch had turned off the threat switch.

When psychologist Robert Kurzban had participants play the “prisoner’s dilemma” game, in which they could choose either to cooperate or compete with a partner for a limited amount of money, an experimenter gently touched some of the participants as they were starting to play the game—just a quick pat on the back. But it made a big difference: Those who were touched were much more likely to cooperate and share with their partner.

In a recent study out of [Dacher Keltner’s] lab…, in general, NBA basketball teams whose players touch each other more win more games.

[S]tudies show that touching patients with Alzheimer’s disease can have huge effects on getting them to relax, make emotional connections with others, and reduce their symptoms of depression.

Tiffany Field has found that massage therapy reduces pain in pregnant women and alleviates prenatal depression—in the women and their spouses alike. Research here at UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health has found that getting eye contact and a pat on the back from a doctor may boost survival rates of patients with complex diseases.

A study by French psychologist Nicolas Gueguen has found that when teachers pat students in a friendly way, those students are three times as likely to speak up in class. Another recent study has found that when librarians pat the hand of a student checking out a book, that student says he or she likes the library more—and is more likely to come back.

The solidaristic implications of touch are ones that I find most intriguing. Not only does skin-to-skin contact seem to contribute to an individual’s well-being, but it has the power to forge social bonds and perhaps to incline us more readily to the common good. Immediately after Simon’s mother-in-law is grasped and helped up by Jesus, “the fever left her and she waited on them.” While I have never quite been comfortable with this quick “recovery” to a role of feminine servanthood, these musings on solidarity give me a more charitable read. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that a disposition of service follows the touch.

If we embrace the significance of touch for living in true solidarity, then it has implications for the way we live our lives as men and women of faith. It is not just for the healers among us.

Recently, as she tries to fall asleep, my two-year-old daughter has been asking – in her charmingly pathetic pleading voice – “Mommy, hold my hand.” It is neither scandalous for her to ask nor scandalous for me to fulfill her request. But the need for touch does not decrease with age or level of intimacy nearly as much as my own cultural context suggests by way of its rules of propriety. And so I find myself wondering who this incarcerated man will have to grasp his hand in the days and weeks to come as he faces life with AIDS.