Joshua 5:9a, 10-12

Psalm 34:2-3, 4-5, 6-7

2 Corinthians 5:17-21

Luke 15:1-3, 11-32

This week’s readings seem to focus on the theme of eating, and particularly the act of shared eating.

The first reading serves as a good point of reference for what follows. The Lord withdraws his provision of manna for the people, who are now able to eat “of the yield of the land of Canaan.” Through this act the Lord tells Joshua that He is removing “the reproach of Egypt” from the people. It is a point to start again, to begin a new life in a new land. The old ways of living from morning to morning are gone, and the Lord’s purposes for the people can now expand and progress into a new stage. Yet it is significant that this transition is accompanied by the celebration of the Passover, the act by which the community recalls and enters into its proper identity as a liberated people.

The Psalm extends the figure of eating through its response: “taste and see that the Lord is good.” For the Israelites wandering their way to the promised land, this tasting was quite literal: in their eating of the manna and their ultimate enjoyment of the produce of the land. But notice that the Psalm verses chosen to go with the response mention nothing about food. The good at issue is rather the psalmist’s relationship to the Lord: the praise, delight, and vindication that comes from the Lord’s saving deeds. What is significant here is that this experience is transitive and communicable. It is not simply for me, but rather a constitutive part of the gladness that comes from God’s steadfast love is that others see it and partake in it as well. Like a good meal, it can only be fully enjoyed when shared: when my tasting and your tasting converge in a mutually acknowledged experience.

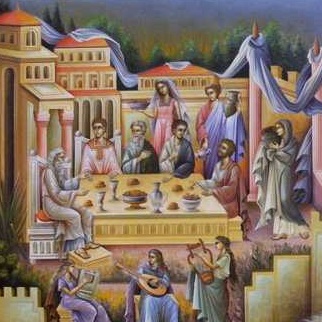

Then of course comes the “main course” in the lectionary readings: Luke’s brilliant rendering of the parable of the Prodigal Son, or as some call it “The Parable of the Two Sons” or even “The Parable of the Merciful Father.” Yet it could perhaps also be called “The Parable of the Mercy Feast” since the culminating scene, and arguably the central focal point proposed to Luke’s audience is the feast held by the father in honor of the return of his son. It is the Jubilee Year of Mercy, a year-long “Mercy Feast” as it were, so perhaps it would be fitting to consider the parable under this title.

Many an exegete and preacher has broken down this parable far better than I ever could. For an excellent theological analysis of the comparative portrayal of the two sons, read (or listen) to Rev. Tim Keller’s interpretation of the text. The one point he hammers home again and again is that by the end of the story, the elder son is in far worse shape than the younger son. It is not simply that he finds himself in a sulky mood and is having trouble adjusting to the sort of welcome offered to his younger sibling; the true tragedy is that his refusal to enter into the feast reveals that he never really knew his father in the first place. What that also means is that he never truly knows himself, in so far as his deepest identity is formed and found in the unconditional love his father has for him.

The younger son is more obviously scornful of his father’s love and so also oblivious to his true self, but in the moment when he finds himself “in a distant country” starving to death, he “comes to his senses” or more literally “comes to himself.” He remembers his father, and so remembers who he himself is. Knowing how the story ends, I have found it fruitful to contemplate at this point how this act of recollection, occurring in such extreme and dire circumstances, is precipitated by the father’s constant remembrance of his lost son. We know the father grieved for his son. We know the father missed him, and longed for his return. How many days did he look off into the distance and wonder where he was, and how he was doing?

The father remembered him. He longed for him. We know that to be true by the way the father responded to the son’s return, and by the small but telling detail that the father did not sell off or otherwise dispose of the younger son’s robe and signet ring. “While he was still a long way off, his father caught sight of him, and was filled with compassion.” How long is a “long way off” though? Could we extend this distance all the way back to the “distant country,” to that moment when—who knows how—the younger son finally remembers who he is? No doubt the abject poverty and starvation played a role, but as anyone knows who’s been around long enough, that by itself isn’t always sufficient. We remember who we are only as we are remembered by others; we come to ourselves only as others come out to meet us.

“While he was still a long way off, his father caught sight of him, and was filled with compassion.” Here is the central statement of what the gospel proclaims to us, and to the world: “God demonstrates his own love for us in this: while we were still sinners, Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8). And what is the outgrowth of this love, this compassion, this encounter? Surely it is the feast at the end. The father embraces his son, greets him with the caress of mercy, but then prepares him for the celebration that is to follow.

The father seems to forget the grave offense committed by his younger son, who by demanding the inheritance conveyed beyond any doubt that he wished his father dead. And that is the (quite understandable) grievance of the older son, who reminds the father of what the younger son did, telling it like it is: “he swallowed up your property with prostitutes!” What an interesting reversal: the father who did not forget his younger son now forgets to be angry. Yet in remembering the offense—holding on to it, as it were—the older son forgets who his father really is, and so who he himself is. He forgets that he is the one who is “always with the father” and who shares in the father’s bounty completely.

The older son obeys the father, but he does not love what the father loves. He does not remember what the father remembers. And so he cannot enter into the feast of mercy which is the ultimate expression of what and who the father is.

If heaven is a feast, then it is a feast of mercy like the one in this week’s gospel parable. The father prepares it for all, and even beseeches the disgruntled self-righteous among us to enter in. But its theme is always the same: merciful love… and memory eternal.