In the days leading up to the papal conclave which just concluded, I became a bit dismayed by the intense, wall to wall media coverage of the event because of two of the forces driving this coverage. The first is our celebrity- and “reality”-obsessed media culture. Recent popes have certainly been treated like celebrities, if of an unusual sort, and I couldn’t help but get the feeling that the viewing audience was awaiting a puff of white smoke the way it anticipates who will receive a rose from the Bachelor. Second, the media coverage was partly driven by the excessive focus on the papacy by some Catholics concerned with doctrinal orthodoxy and reverent worship. Of course, the pope plays a crucial role as the universal pastor of the church and as the head of the vast administrative apparatus of the Catholic Church, but it is easy to overestimate the influence the pope has over the actual practice of Catholics. Apart from a few changes to the liturgical text at Sunday worship, I have a hard time thinking of any ways the practice of my faith has changed as a result of the eight years of Benedict XVI’s papacy. The daily practice of Catholic faith has much more to do with our local parishes and communities. While I certainly believed the election of a new pope was momentous, I couldn’t help but feel the whole production was overblown.

I have to admit, however, that as the chances of a conclusive vote increased, and especially when the white smoke began billowing out of the chimney, I caught a bit of conclave fever. After we learned that Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio had been elected and taken the name of Francis, and we all scrambled to catch up on who this man was, I realized that we may have been watching a more pivotal moment than I had thought.

Everyone paying any attention knows that the cardinals were largely agreed that two issues crucial for the new pope to tackle are reform of the Curia and the New Evangelization. The Catholic faith has over time grown less relevant to people’s personal lives and less influential in society, and the corruption and instinct for self-preservation within some precincts of the Curia has not only contributed to this problem, but also tied the hands of those with the most authority to do anything about it. Some have argued that the church could become more relevant by changing apparently outmoded teachings, especially in the area of sexuality, while others have claimed that the solution is for the church to more forcefully and consistently present its teachings. By electing Bergoglio, however, I believe that the cardinals took a daring and hopeful gamble: that the problem is not so much with the teachings themselves, but with how the teaching authority is being exercised.

We need to think more clearly about the distinction between authority on morality and moral authority. In the context of the Catholic Church, authority on morality refers to the magisterium’s authority to teach on matters of morals. Moral authority, on the other hand, refers to the credibility that comes from practicing what one preaches. By making this distinction, I am in no way suggesting that the authority of the bishops to teach on morality is dependent on their moral character, as if their teaching could be disregarded as a result of their moral failures. What I am suggesting is that if we are going to talk about the exercise of authority as teaching, then we must put as much emphasis on the persons being taught as we do on what is being taught and by whom. The Second Vatican Council’s Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, Dei Verbum, asserts that divine revelation is first of all an encounter with God Himself, most completely fulfilled in Jesus Christ (##1-4). If the bishops intend to teach faith, “by which man commits his whole self freely to God” (#5, quoting from the First Vatican Council’s Dogmatic Constitution on the Catholic Faith), then the bishops must teach in a way that touches the whole self: mind, will, and body. The believer must not only be able to accept the teaching as true, but judge it to be good and visibly see it in action.

The Gospel of Matthew provides some insight into this exercise of teaching authority. After Jesus preaches the Sermon on the Mount, the gospel reports that “the crowds were astonished at his teaching, for he taught them as one having authority, and not as their scribes” (7:29). This passage seems to set up a dichotomy between the authority on morality of the scribes and Pharisees, and the moral authority of Jesus. Yet much later, after Jesus has arrived in Jerusalem, he says, “The scribes and the Pharisees have taken their seat on the chair of Moses. Therefore, do and observe all things whatsoever they tell you, but do not follow their example. For they preach but they do not practice” (23:2-3). Jesus thus recognizes the scribes’ and Pharisees’ authority to teach on morality. What then accounts for the crowd’s perception that Jesus had an authority lacking in the scribes and Pharisees? It cannot be merely “charisma”; Jesus provides the key with his accusation that the Pharisees do not practice what they preach. As Dei Verbum states, Christ revealed God through “deeds and words having an inner unity” (#2) similar to the unity of deeds and words we recognize as moral integrity.

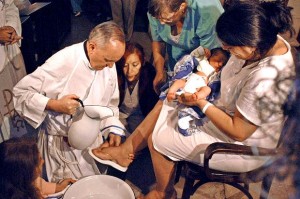

Since Bergoglio’s election, the stories of his pastoral practice have instantly endeared him to the public. He rode to work on the bus. He gave up the archbishop’s palace for an apartment and cooked his own food. He washed the feet of AIDS patients at a hospice. People were instinctively drawn to his humility, reflected in his choice to name himself after the most humble saint, Francis of Assisi. Bergoglio clearly exercised his episcopal authority as archbishop with true moral authority.

Since Bergoglio’s election, the stories of his pastoral practice have instantly endeared him to the public. He rode to work on the bus. He gave up the archbishop’s palace for an apartment and cooked his own food. He washed the feet of AIDS patients at a hospice. People were instinctively drawn to his humility, reflected in his choice to name himself after the most humble saint, Francis of Assisi. Bergoglio clearly exercised his episcopal authority as archbishop with true moral authority.

Earlier this week in one of my undergraduate classes, we wrapped up a unit on teaching authority in the church by looking at the sexual abuse crisis in the Catholic Church in Ireland, revealed in the Ryan and Murphy Reports in 2009. Here we find a very different vision of episcopal authority. Marie Collins, a victim of abuse, writes of her experience trying to get to the bottom of things:

My anger and disillusionment grew over the next months. Numerous attempts to get assurance from the Church that this admitted abuser was not in a parish and would never again be in a ministry in contact with children met with equivocation. The archbishop found my queries “difficult questions.” How could an archbishop of my Church, knowing a man was a paedophile, find it difficult to decide if he should be in a position of trust with young children? The Church always found it so easy to have a moral certainty in how I should live my life – what was morally right or wrong was black and white, no grey areas allowed. Did this only apply to little people like me but not to those in higher places?

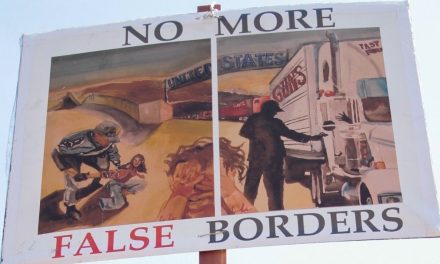

Eugene O’Brien writes that here we have the conflation of two distinct “modes of knowledge”: “It is as if because the message of the Church is ethical and moral, then ipso facto their behaviour must also be seen as ethical and moral and any abuse is just an aberration which can be glossed over by the Church’s overall message.” In other words, authority on morality is confounded with moral authority. Collins’s account foreshadows the outcome of such a conflation: “The men in leadership, surrounded as they are by like-minded people and living in a world of canon law and arcane tradition, have completely lost touch with the origins of the Church and with the people who – they constantly tell us – are the Church.” Although there are certainly other causes, a major cause of why we need a New Evangelization in the first place is that the church’s authorities have lost touch with the people they serve.

Of course, the covering up of pedophile priests is an extreme case, but it is symptomatic of a larger pattern of clericalism, which, as archbishop, Bergoglio denounced in his own clergy. Pope Francis offers the possibility of a radical change in pastoral leadership. Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI were themselves personally holy, but given the state of leadership in the church today, it cannot be said that they insisted on moral authority as a necessary component of episcopal authority.

The cardinals are taking a gamble that Francis’s pastoral approach can be a more effective way of evangelization than the assertions of authority of the past. In another of my classes, I asked my students which of the five models of the church outlined by Avery Dulles they find the most appealing. Overwhelmingly, both Catholic  and non-Catholic students are drawn to the Servant model, which envisions the church as sharing the concerns of the world and serving others. One of my colleagues, who has researched the sexual values of students at Catholic institutions, including our own, believes that Catholic teaching on sexuality can appeal to students if it is expressed in terms of dignity, respect, and justice. Bergoglio seems to have taken a pastoral approach consistent with these insights, focusing on the church “accompanying” the people it serves.

and non-Catholic students are drawn to the Servant model, which envisions the church as sharing the concerns of the world and serving others. One of my colleagues, who has researched the sexual values of students at Catholic institutions, including our own, believes that Catholic teaching on sexuality can appeal to students if it is expressed in terms of dignity, respect, and justice. Bergoglio seems to have taken a pastoral approach consistent with these insights, focusing on the church “accompanying” the people it serves.

I say that this pastoral approach is a gamble for two reasons. First, proposing the faith through the unity of deeds and words calls forth a response from the person, but that response can be negative. The clericalist approach by its nature seeks to control, whereas moral authority lets go of the need to control, opening the door to rejection. Second, by electing Francis, the cardinals have posed a challenge to themselves and the broader church to adopt a new pastoral attitude. Will Francis’s humility translate into weakness as a leader, unable to hold his Curia to the same moral standard to which he holds himself? And, as I mentioned, the pope has little direct influence over the daily practice of Catholicism. Any broader transformation of the church will depend on whether or not Catholics are willing to look to Francis as a model for their own faith.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks