In recent days, the dire situation at the southern land border of the United States has been omnipresent in the news. Much of this is driven by politicians’ craven estimation that there are votes to be gained by drumming up nativist tendencies, particularly if it distracts attention from otherwise popular policies enacted by their opponents. Regardless of the rationale, there is little disputing that the influx of migrants, especially unaccompanied children, at the U.S.-Mexico border has overwhelmed the system and demands attention.

But then again, is there such consensus?

The story of the week seems to be the Biden administration’s semantic contortions to avoid using the term “crisis” to describe the situation. Apparently, they fear that calling it a crisis will leave them vulnerable to further political attacks, and so they are clearly dead set on steering clear of the word at all costs. The result, which would be comical if not so tragic, is that the conversation now focuses less on the actual issue—human beings in dire need of assistance and little infrastructural support to guarantee that assistance in a just and expedient way—and more on the scoring of political points.

Here, I think, the Biden administration could benefit from the president’s own faith tradition. The truth of the matter is that there is every reason to call the current situation at the border a crisis—provided that we are also ready to say that the crisis is not a new development, but merely a reflection of a long-overdue reckoning with a truth that we have collectively tried so hard to ignore.

This declaration requires a challenging shift in our moral awareness, one that is just as difficult people living in the United States to accept as it is necessary for Catholics to embrace. It requires expanding our notion of who deserves our attention, so that we are ready to include more than just our “fellow Americans.” It requires accepting, in the words of St. John Paul II, that “we are all really responsible for all” (Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, no. 38) in just the way that we have heretofore been unwilling to do.

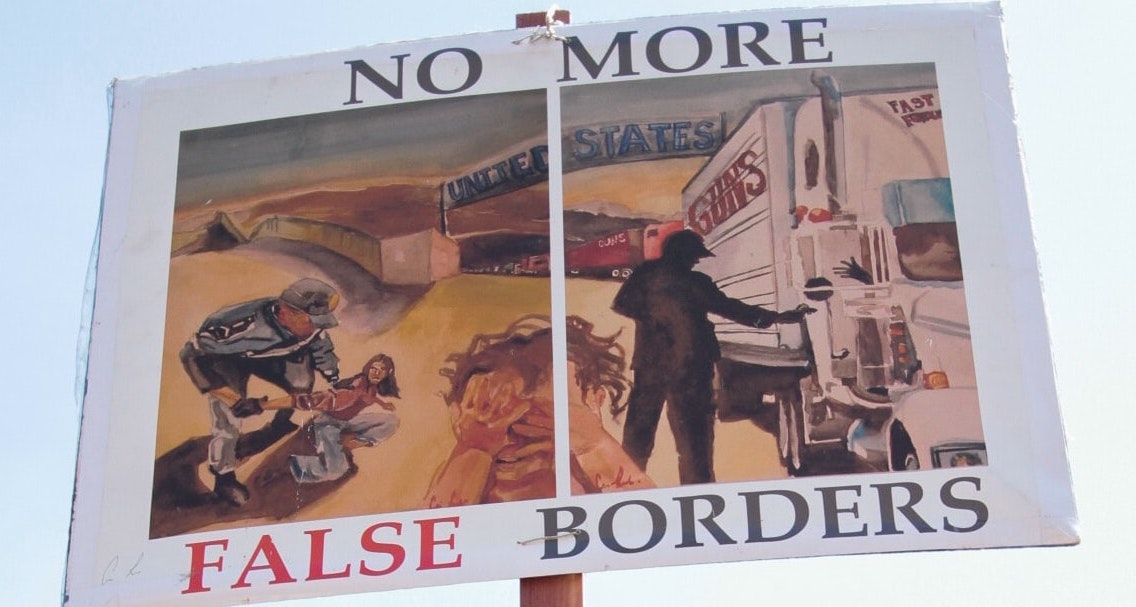

At the moment, the current media narrative suggests that there was no crisis at our border until a few short weeks ago. This shared fiction was made possible by our willingness to believe that everything was perfect at our border as long as we never had to see the suffering and hardship of Central American migrants directly. When everyone had to “remain in Mexico,” we were able to pretend that there was no suffering—to say nothing of humanitarian crisis—at our southwest border, because we never had to confront it.

We told ourselves this story and we believed it, because it was far easier than addressing the reality that as a direct result of our unwillingness to see the suffering of our fellow human beings, their suffering amplified. From disease, to sexual assault, to kidnappings and beyond, the migrants who fled heart wrenching conditions in their home countries in search of safety and security found neither and instead suffered more because we assumed that as long as they were only on our doorstep and not actually in our house, then their struggles could not possibly be our problem.

This narrative is not simply built on a lie. This narrative is a lie.

The lie is that we can deny suffering simply by willfully choosing not to see it. This assumption not only flies in the face of traditional Catholic moral categories like Thomas Aquinas’s distinctions between vincible and invincible ignorance, it also reflects our national inability to do precisely what Pope Francis has insisted we must: that is, see ourselves “not simply as a country but also as part of the larger human family.” Countries that fail to embrace “this gratuitousness,” Francis asserts, “err in thinking they can develop on their own, heedless of the ruin of others, that by closing their doors to others they will be better protected” (Fratelli Tutti, no. 141).

A more direct indictment of our preferred prevarication would be hard to imagine.

As Catholics, we have an obligation to end this lie and to speak out against the error in our popular narrative that suggests there is a newly emerging crisis at our border. We must instead adopt the moral clarity that comes from what Johann Baptist Metz described as the “mysticism of open eyes.” As he explained,

“A mysticism of open eyes…is a mysticism that especially makes visible all invisible and inconvenient suffering, and—convenient or not—pays attention to it and takes responsibility for it, for the sake of a God who is a friend to human beings.”

(Passion for God, 163)

My colleague Ryan Duns, SJ, likes to stress to the students in our team-taught introductory theology class that this mysticism of open eyes is incumbent on all Christians, because it is the message at the heart of the Cross: God refuses to ignore any kind of human suffering, but instead has chosen to experience it from the inside, despite the inconvenience. If we truly believe in Christ crucified, then we must do the same.

With the benefit of this graced perspective, we can more clearly see the truth of the crisis at our southern land border. We can see that the crisis did not appear in the last few weeks as a result of some new administration policies, which is what some politicians want us to believe (because that narrative boosts their political fortunes). Rather, we can admit that those policies simply created the conditions that made a once-hidden truth plain for all to see.

If we are truly committed to the mysticism of open eyes, though, we will not stop at this recognition. We will instead push further to acknowledge the fact that the suffering that has long been at our nation’s doorstep is intimately linked to the actions we, as a nation, have taken out of our own “narrow and violent nationalism” (Fratelli Tutti, no. 86)–actions that have often made conditions so untenable in foreign lands that people have had no choice but to flee in search of new opportunities in new places. (For detailed analyses of the ways the United States’ pursuit of its economic self-interests have harmed our neighbors to the south and prompted some of the migration we are now recognizing in the “current” crisis, see Kristin Heyer’s Kinship Across Border: A Christian Ethic of Immigration.)

None of this will be easy to acknowledge, but all of it will be essential if we are ever going to move beyond political posturing and toward a real response to this crisis of our own making. Inspired by Christ’s example, let’s embrace the mysticism of open eyes and, as Catholics, lead the way to a new, more honest form of civic discourse.