Isaiah 61:1-2, 10-11

Luke 1:26-50, 53-54

I Thessalonians 5:16-24

John 1:6-8, 19-28

I was a bit of troublemaker in junior high school, a class clown for whom the principal’s office and the detention hall were not all that unfamiliar. Of all my disciplinary interactions with the various school authorities I remember almost nothing, with the exception of one short adage which the guidance counselor had mounted above her desk in one of those old multi-page banners you used to be able to make so easily with the printer paper that was already attached and had the tracking strips on each side. It was one of those omnipresent clichés of childhood mediation: “If nothing changes, then nothing changes.” Strangely enough, though, that phrase has continued to pop into my mind as I have grown older (and hopefully wiser), and has expanded in its complexity and scope of application.

The surface meaning of the phrase, of course, is that one should not expect different results from identical actions and conditions. “If you keep misbehaving in Mr. Kitney’s class, you’re going to continue to get into the same kind of trouble.” The principle could just as easily be applied to society and history, however. The ancients were not entirely naïve or irrational to think that everything in the cosmos, including human history, were caught up in an eternal recurrence of cyclical patterns. Everything that is and will be has been before, and thus it is illusory to imagine there has been or ever will be anything truly “new under the sun.”

Indeed, I think if one lives long enough, the evidence for this view can only grow. I just listened to a fascinating (and funny) story on the NPR program This American Life which sought to gauge interest in time-travel among elderly people. To the interviewer’s surprise, it was not any logistical inconvenience or prudent fear of chronological intervention that made the older men and women scoff at the idea of time travel; it was rather the settled conviction that it ultimately would not make any difference in the end. Human beings will continue to tread the same path they always have, and the dynamic forces that shape history will continue to exert the same influences in the same ways. I myself already feel a twinge of this ennui as I read the newspaper and encounter my fellow community members each day: the world will continue to spin on, one era giving way to the next, with only superficial differences to distinguish them.

I would submit that if there is any central, overriding theme to the lectionary readings of Advent, it is that this view of history and society is mistaken. More pointedly, what the Advent scriptures repeatedly affirm is that the manifestation of what is truly and authentically new (novitas) is not merely an integral part of human history, but rather the deepest meaning of that history. After all, if novitas is merely one more phenomenon or “ingredient” in the cosmos, then it could just as easily be incorporated into the eternal cyclical patterns as anything else. Yet the view of history that emerges from the Bible, and that is on such poignant display during this season, is that time is itself a creature, and that its highest purpose and dignity is to serve as a vehicle for the in-breaking of the divine. This in-breaking is always new, it is always sui generis; yet it comes to its culmination in the person of Jesus Christ.

There is a penultimate novitas, however, in the person of John the Baptist. One can understand (or, in my students’ lexicon, “relate to”) how the central tenets and categories of the Christian faith unfolded from the personal interaction of the apostles with One whom they believed to be both Messiah and Lord (Adonai). What is more difficult to understand, however, is how that belief ever began to take root in the first place. Monty Python’s The Life of Brian seeks to gain comical leverage from the implausibility of such a development: that a normal-looking peasant in a normal town with a normal family and a normal-sounding name could be proclaimed to be divine. Sure, the people were hungry for demagogues (as people always are), but why and how go that next step and declare someone to be God-with-us?

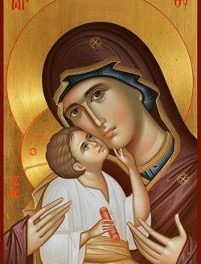

In my own admittedly limited grasp of the Scriptures, it is John the Baptist who serves as the catalyst and turning point for this sort of public recognition. We may presume Our Lady and St. Joseph knew, to a varying extent, the true identity of their son. Yet how could that knowledge ever be translated into any kind of public claim that could be understood and taken seriously? Enter John the Baptist.

The one thing about John the Baptist to which I continue to return is his eccentricity. Even by standards of the time, a time in which such eccentrics had an esteemed place, he stood out. There is very little doubt in my mind that he would be considered mentally ill had he lived today, and indeed many today do in fact see him through that lens. Moreover, his eccentricity was not entirely benign. One could certainly not call it “tame” or “cute.” Yet it was precisely through this eccentricity, this novitas which served to confirm his authority as a prophet, that his “cry in the desert” was able to be heard and received by those who would go on to follow Jesus and receive the Holy Spirit upon His resurrection.

The authorities of the time had a category prepared for him: “Elijiah,” the forerunner and herald of the Messiah. And in Matthew 11, Jesus is depicted as explicitly identifying John with this role. Yet in the gospel for today, the Baptist rejects this title, and simply declares himself to be the one “crying out in the desert, ‘make straight the way of the Lord!’” Like Jesus after him, his “non-answer answer” has a deeper point than evasion: it is a sign that what is being manifested and inaugurated in the midst of that time and place has no pre-existing conceptual category which can accommodate it. What is breaking in upon the scene is truly and ineffably new. What is unfolding has not unfolded before, what emerges is not a part of any greater, repetitive cycle. The divine action and presence among us is God-as-God-has-never-been-known-before, always greater and better than what our minds can imagine or anticipate.

Each Advent, we remember that something new has come and continues to come into the world, and because of this newness, we believe change is possible.