Today’s announcement from the White House perhaps offers a compromise in the complexities of church/state relations. I am sure that there will continue to be responses to this new move in the days to come, but initially it seems that the shift allows for more of a range of religious freedom than the previous mandate, and many people will likely see it as a welcome compromise. (Edited to say: I see I spoke too soon – looks like there remain numerous questions about religious liberty and so on. Which makes a more thorough THEOLOGICAL discussion about women’s health all the more important.)

So I want to turn back to the other question raised in this debate, a crucial question that never quite made it to open air, but which needs much more thought and scrutiny: women’s health. I’m concerned, especially about the dichotomy that has operated throughout:

Government = respects women enough to let them make their own choices, gives them ABC to help them choose

Bishops = trying to dictate women’s reproductive choices make women unfree

I’m concerned about this dichotomy because it operates too closely on the idea that women always have a “choice” about reproduction, in ways that guilt women and ultimately harm all of society.

Of course, planning and/or spacing children helps women. Whether by using ABC or NFP – clearly does reduce unintended pregnancies and that could be good for all sorts of reasons. (For the purposes of this discussion, I am not calling into question the scientific nature of NFP; there are plenty of medical researchers who have published findings on NFP and its efficacy in reputable peer-reviewed journals. Whether there is disagreement about those findings or not, I don’t know – but I leave that question more to debate among science researchers and others with greater access to those details. I would here rather take the studies charitably and at face-value: that NFP works, and that the studies the Obama Administration relied on for its mandate are also true.)

Regarding the importance of spacing children, I don’t think that the government, and the church and its bishops, are in disagreement. Catholic teaching supports worrying about and caring for women’s physical and mental health, as well as children’s health. And indeed, both the church and the government have spent money working toward helping women be able to plan pregnancies better. For the church, this money has been spent in the form of developing more accurate and easier-to-use forms of natural family planning (in comparison with traditional medical research that has developed more accurate and easier-to-use forms of artificial birth control) – for example, see nfp.marquette.edu for an NFP method making use of a fertility monitor, and which its developers tout as user-friendly.

Where one of the most likely disagreements, at the heart, is Humanae Vitae‘s emphasis on abstinence as a way to space pregnancies. From the point of view of secular society: abstinence is hard, and, really, unrealistic. The hypotheticals often given are not-so-hypothetical: women in abusive households where they can’t depend on the fact that men might abstain; women who simply don’t want to abstain because they like having sex; women who don’t like focusing on having sex exactly at the point in the month when they least feel like having sex (because while the most fertile periods make many women feel hornier, the less fertile periods make women feel exactly the opposite); women who don’t like having to postpone loving their partners. In addition to all this, NFP trainers sometimes make women (and men) feel like every single sex act must be this absolutely mind-blowing awesome experience, but real sex isn’t like that, not all the time. A “choice” for NFP doesn’t always look like a wholly free individual choice, and that seems a large problem, especially in a secular culture that focuses heavily on individual choice.

Those are real issues and real problems, and they are quite worth thinking through.

I worry about all of us women, though, if and when we reject those methods for being unrealistic and idealistic, or for cutting off “choice”, if we don’t also examine some of the effects of contraception as a whole, too.

For example, I think about hook up culture on the college campuses where I’ve lived and worked. I won’t try to make a case of causation here (which I think never works when it comes to discussions of human behavior anyway), but I think it’s pretty difficult not to see at least a strong correlation between the ways women and men interact with each other on Friday and Saturday nights, and their access to contraception. I particularly worry about women and women’s choices.

Here’s why I wonder whether it is the case that people are able to be fully themselves in a hook up/easy sex culture. What I see when I’m visiting a restaurant on a weekend that happens to be next to a bar, are women that are dressed up, high heels, make up, little dresses – presumably to impress, and hook up with, men who are, well, not that well dressed. It makes me think that maybe women especially, are expected to put out their bodies. But even more than that, researchers (like Donna Freitas’ book Sex and the Soul) looking into college hook up culture have found that when they ask women questions about hook up culture, the answers are often that the women are seeking relationships of intimacy, but sex is the only way they see to have that intimacy. One person Freitas interviewed said, “If you have a pattern of doing certain things, then that kind of becomes noticed. Everyone is like, Oh she is a slut. She hooked up with that guy, that guy, that guy.” And that becomes its own self-fulfilling prophecy, because then people expect her always to do that. Men, on the other hand, have said that they feel pressure to be “players” – and that they therefore feel like they can’t develop intimate relationships one on one, because of the pressure to always be exploring new and different bodies. So – it all makes me wonder, does hooking up, free sexual relationships, give people the kind of intimacy they deserve?

That kind of culture (which is, I think, a bit of a microcosm for how we often talk about and understand sex in conversations beyond the university) couldn’t exist without the fact that women have options “controlling” their bodies so that sex really does seem unattached from any other kind of commitment, including commitments toward intimacy, compassion toward others that doesn’t objectify them, and so on. (I’m not sure, in conversation with my own students, how much of an option many of these college girls feel they have in terms of having sex, but that’s probably for another blog post.)

But beyond that question of the ways in which contraception perhaps encourages – or at least permits – objectification of women’s bodies, let’s talk more about the “controlling our bodies” bit. To what extent do we have control? And if the rhetoric is “Birth Control is as Pretty Darned Close to Perfection as You Can Get”, can women be faulted for wondering why the #&%^& pill didn’t work if there’s an “unintended pregnancy”?

The Guttmacher Institute (secular, non-politically-aligned) discusses the incidence of unplanned pregnancies in relation to contraceptive use. Only five percent of consistent, correct users of birth control have unintended pregnancies. That’s a pretty good number, though we must remember: that 5% means that 5 women out of every one hundred get pregnant in the course of a year. The other thing is, only 2/3 of women are consistent correct users. The 20% of women who use contraception, but incorrectly or inconsistently, account for 43% of unintended pregnancies. It would be interesting to break down those numbers further: why is there incorrect or inconsistent use. Other groups have done such studies to see why women stop using particular contraceptive methods (including NFP here, though I know many will protest its being mentioned as a contraceptive) and the reasons range from “not convenient” to “didn’t feel good” and so on.

My point in raising all this is that while we do have some modicum of control over bodies and sex in relation to birth control (NFP included), there’s a limit. When the rhetoric about the pill and other forms of artificial birth control is so strongly aimed at “Take me and never fear about pregnancy” – even when 5% of perfect users still get pregnant over a year’s time – we seem in pretty high danger of lying to ourselves. And we ignore that limit to what birth control can do and give women guilt trips about getting pregnant: “Oh, why didn’t you be more careful?”

So the blame, culturally, is still largely on women, and women’s bodies and women’s need to control and regulate themselves. Of course, this, too, is against women. And, of course, access to abortion (together with the rest) means that the unwanted pregnancy is either aborted or that child is the woman’s choice. That puts the pressure on her and takes it off of her “village” (whether by “village” we mean family/friends or government support). The pressure is pushed toward women.

In other words, now that we’ve had several decades and couple generations of using birth control, I’m not sure but that in many ways we aren’t still back where we were to begin with, before birth control came full swing into use: women’s bodies sometimes have children. That continues to create all sorts of tensions, changes in relationships, concerns about work and women’s labor and women’s health and so on.

The questions and the problems don’t disappear simply because contraception exists. The problems have shifted, and maybe intensified, especially for the ones who find themselves on the wrong end of a statistic.

So are we all guilty of perpetuating idealism in one form or another? Artificial birth control has an ideal narrative about sex as an open choice for all, without the attendant problems previous generations had. Natural family planning has an ideal narrative about abstinence, which relies on an ideal of an egalitarian relationship between men and women who can choose, together, not to have sex.

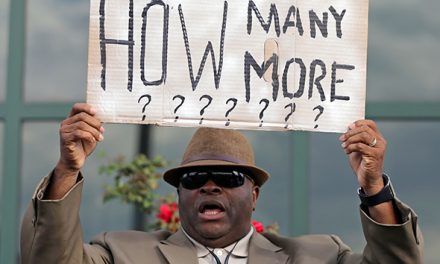

In the interest of “free choice”, discussing these two narratives and their importance for women’s health is imperative. The operating dichotomy does not work – and I think women’s health deserves deeper reflection than the dichotomy permits.

I am sorry I created a policy about non-one-line responses. Because all I really want to write here is “Amen.” So… amen.