Pope Benedict XVI, upon his arrival in Mexico [English links from Vatican transcript] on Friday,said that his goal in this apostolic visit was to encourage Mexican Catholics to “revitalize their faith” so that they may “act as a leaven in society, contributing to a respectful and peaceful coexistence based on the incomparable dignity of every human being, created by God, which no one has the right to forget or disregard.”

After reading these powerful words, I expected that Pope Benedict’s public addresses over his three-day visit would focus on the Catholic Church’s social ethics and how this tradition of the Church could helpfully contribute to political discernment on what ails Mexico and what can be done. Perhaps his private conversation with President Calderon did invoke this tradition of the Church, but the rest of the pope’s public addresses focused on personal faith to the neglect of social responsibility, human rights discourse, or any mention of the role of the institutional Church in combatting violence.

The theme of “hope” was apparent in all public addresses. In his welcome remarks, the pope explained:

As a pilgrim of hope, I speak to them in the words of Saint Paul: “But we would not have you ignorant, brethren, concerning those who are asleep, that you may not grieve as others do who have no hope” (1 Th. 4:13). Confidence in God offers the certainty of meeting him, of receiving his grace; the believer’s hope is based on this. And, aware of this, we strive to transform the present structures and events which are less than satisfactory and seem immovable or insurmountable, while also helping those who do not see meaning or a future in life. Yes, hope changes the practical existence of each man and woman in a real way. Hope points to “a new heaven and a new earth” (Rev. 21:1), that is already making visible some of its reflections. Moreover, when it takes root in a people, when it is shared, it shines as light that dispels the darkness which blinds and takes hold of us. This country and the entire continent are called to live their hope in God as a profound conviction, transforming it into an attitude of the heart and a practical commitment to walk together in the building of a better world. As I said in Rome, “continue progressing untiringly in the building of a society founded upon the development of the good, the triumph of love and the spread of justice.”

Together with faith and hope, the believer in Christ – indeed the whole Church – lives and practises charity as an essential element of mission. In its primary meaning, charity “is first of all the simple response to immediate needs and specific situations” (Deus Caritas Est, 31), as we help those who suffer from hunger, lack shelter, or are in need in some way in their life. Nobody is excluded on account of their origin or belief from this mission of the Church, which does not compete with other private or public initiatives. In fact, the Church willingly works with those who pursue the same ends. Nor does she have any aim other than doing good in an unselfish and respectful way to those in need, who often lack signs of authentic love.

Here, the pope explains that when a believer has hope in God, he or she is empowered to build a better world. And Christians should work to build a better world, a more just and loving world. Hope leads to charity, and we are called to do our part to alleviate suffering. The mission of the Church includes this aim of alleviating suffering in the world and working to transform the unjust structures of the world. That’s the extent of the pope’s exhortation rooted in social ethics on this visit.

Yesterday, in a meeting with young people at the Plaza de la Paz (Guanajuato, Mexico), the pope acknowledged the suffering of vulnerable children:

You have a very special place in the Pope’s heart. And in these moments, I would like all the children of Mexico to know this, especially those who have to bear the burden of suffering, abandonment, violence, or hunger, which in recent months, because of drought, has made itself strongly felt in some regions.

His focus was on personal prayer and individual discipleship animated by joy:

If we allow the love of Christ to change our heart, then we can change the world… So I invite you to pray continually, even in your homes; in this way, you will experience the happiness of speaking about God with your families. Pray for everyone, and also for me. I will pray for all of you, so that Mexico may be a place in which everyone can live in serenity and harmony.

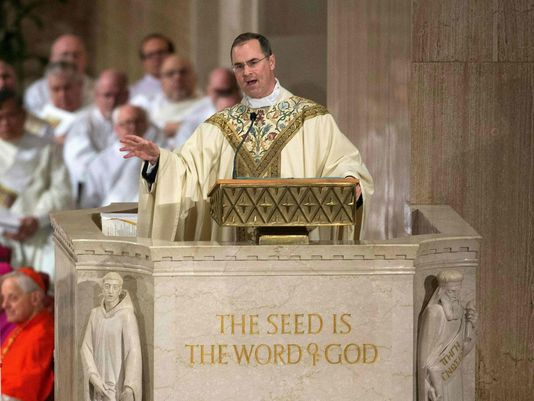

In his homily today (Expo Bicentenario Park, Leon, Mexico), expressed the need for believers to place trust in God:

A pure heart, a new heart, is one which recognizes that, of itself, it is impotent and places itself in God’s hands so as to continue hoping in his promises…The history of Israel relates some great events and battles, but when faced with its more authentic existence, its decisive destiny, its salvation, it places its hope not in its own efforts, but in God who can create a new heart, not insensitive or proud. This should remind each one of us and our peoples that, when addressing the deeper dimension of personal and community life, human strategies will not suffice to save us. We must have recourse to the One who alone can give life in its fullness, because he is the essence of life and its author; he has made us sharers in the same through his Son Jesus Christ.

It is a curious emphasis– that “human strategies will not suffice to save us.” That we hope not in our own efforts but in God’s. Some might wonder if the focus on God’s agency and our humility serves to adequately confront the real terrors that threaten Mexico: from dehumanizing poverty to the violence of the drug cartels, to the corruption in politics and policing. The pope seems to acknowledge these struggles by referring, later in his homily, to “distressing situations of human suffering” as he invites those in attendance to recover a sense of “joy” in Christian discipleship. He concluded by asking for the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary, inviting her to protect “her Mexican and Latin American children, that Christ may reign in their lives and help them boldly to promote peace, harmony, justice, and solidarity.”

As I reflect on the pope’s words, I think back to my conversations with Tijuana residents over the last few years. I wonder how they are reacting to this papal visit. Do they hear this call to prayer as empowering, confirming that God is on their side in this complex struggle? That they should continue to have hope in God’s providence? Or do they say, “Your Holiness, we’ve been praying! What else can you suggest?”

I think that to evaluate Pope Benedict’s statements in Mexico, you have to consider the context of church-state relations in Mexico.

The Mexican Revolution of 1917 was extremely anti-clerical. Mexico’s constitution forbade Catholic schools and religious orders, made the state the owner of all church property, and denied the church any legal status. It also stated, in Article 130, Section 9: “Neither in public nor private assembly, nor in acts of worship or religious propaganda shall the ministers of the religions ever have the right to criticize the basic laws of the country, of the authorities in particular or of the government in general; they shall have neither an active nor passive vote, nor the right to associate for political purposes.”

These restrictions led to the Cristero Rebellion beginning in 1926. In the 1940s, church and state came to truce in which these laws would stay on the books, but would simply be ignored, with the exception of Article 130, Section 9. It was a sort of bargain, that if the church became openly critical of the government, then the government would bring the full force of the law against the church.

In the 1980s, the church became more openly critical of the government (perhaps thinking that given the church’s active role elsewhere in Latin America, the state would not dare fight back). In 1992 the government lifted all the legal restrictions on the church.

However, there still remained the long tradition of anti-clericalism and lack of church involvement in political issues. Also, another thing to consider is that the two leftist parties, the PRI and PDR are still largely anti-clerical, while the conservative party, PAN (the party of President Calderon), is openly Catholic. Given that context, public political statements by the church can give the appearance of partisan support.

So I think Pope Benedict is trying to navigate that complicated history. Perhaps he does not want to put the Mexican bishops in an awkward political situation. I am not saying he is right or wrong, just that the context matters.

Thanks, Matt. You make excellent points here about the context and history in Mexico. I know that some were already saying that the timing of this visit was being perceived as a boost to Calderon because they are in the final stretches of campaigning in the presidential election. I’m sure that there was a great deal of thought given to these factors, and there are probably lots of other issues I don’t know about. 80% of Mexicans identified as Catholic in the 2010 census (even though less than half attend church weekly). So some observers were also talking about this as a way for the pope to bring his message of the New Evangelization to a country with deep Catholic roots.

Emily, that is a good point that the context also involves the election.

Also, John Allen points out that in his comments on the plane ride to Mexico, Benedict does seem to be advocating a more public role for Catholic faith, particularly on matters of social justice: http://ncronline.org/blogs/ncr-today/pope-gives-new-twist-pro-life-rhetoric