…at least according to this NPR essay. Quoting David Campbell, Notre Dame poli sci prof:

“Our findings indicate that for many but not all Americans, when they’re faced with this choice between their politics and religion, they hold fast to their politics and switch religion, or more often switch out of their religion,” he says.

And, NPR goes on to note:

A recent Stanford University study found that people are more likely to have hostile feelings toward people of the other party than members of another race.

And:

the percentage of people who said they would disapprove if their children married someone from the other party has spiked from 5 percent to 40 percent.

Wow. Many of us who teach theology have been well aware of the increasingly voluntaristic nature of religion in the past couple decades. What we have perhaps been less aware of is the apparent decrease in the voluntaristic nature of political parties – that it forms so trenchant an identity marker.

Less aware – but maybe not surprised. Many of those aspects of society that people have pointed out in the past couple decades perhaps come to a focal point in political party as identity:

- Increasingly mobile society – in a world where biological family members are split across several time zones, people often speak of their new “urban” families, and it’s become part of the story we tell about ourselves. The sitcom “Friends” might have been a preview of this kind of family, but many novelists from Helen Fielding to Nick Hornby have also noted the “urban family.” Urban families seem to consist largely of peoples’ friends, people with whom they have significant agreement on many ideas, even as these urban families also provide some of the help – the moves, the socializing, the drives to the ER – that close-knit biological families once did. Such coalescing around like-minded people makes belonging to a political party that functions similarly seem natural.

- Increasingly global society – One of the points scholars have made about globalization is a decrease in nation states and in local politics, and a corresponding rise in mega-cities. Thus places like Laos and Mumbai hold increasing importance, even as their respective nation states hold relatively less importance. Our focus is trained on these mega-cities, which means we worry far more about what happens in DC (not the most important of the global cities, but no shabby player, either) than we do in our own localities. (My last local election for mayor is a case in point – only 2000 people turned out for the primary, out of a population of about 145,000, the lowest number on record…. A 10% turnout has been typical in these mid-cycle primaries in the past – so people were highly blindsided by this low, low turnout – especially in a year when there were 3 candidates for mayor and a heavily contested and advertised campaign, to boot) But when our gaze is so concertedly focused on these mega-cities, our sense about what moves and shakes the world changes too. Political parties, tied especially as they are to gazing at Washington – which of course affects our lives, but not to the extent that our single-minded focus suggests – are a natural fit for seeking identity in a global world.

- Increasingly religiously “none” – Surely it occurs to more than one person that it is perhaps also the case that as the religious “nones” are on the rise, a need for political party supplants religion? Indeed, some scholars of religion have long suggested that American politics and patriotism already function as a religion – at least in some of the broadest definitions of religion (definitions like those of Clifford Geertz). A person can have ritual and creed tied together in a political party and its various activities. While “nones” still proclaim a liking for spirituality of the traditionally religious sort, it’s easy to combine vague spiritual feelings and practices with strong political leanings – easier, indeed, to do that, I suspect, than it is to combine strong religious practice with vague political leanings. (That’s part of what I take away from the point that people more easily change their religion to fit their political party’s leanings.)

There are more bullet points I could address, I am sure. But I want to highlight how intensely important it is, in this kind of arena, for there to be people like Matt Malone wanting to proclaim Christ first, even and especially at a magazine called America. I think what it means to focus on Christ above all else is to recognize:

- The family God gives us in the Church – the brothers and sisters with whom we do not share as much in common with as we do with our urban families. Living with this family takes on increasing importance, especially for helping us to learn humility about our own positions and ideologies, and for learning how to love those who are not at all like us. Seeking, in a concerted way, to be that kind of community is a good witness to Christ, I think.

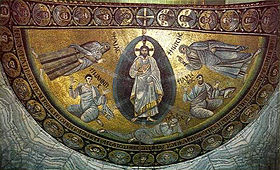

- The Church is both global and local, and nowhere is this made more clear than in our practice of the Eucharist. But this is a global and a local that act to shake up the ways we tend to imagine global and local. Bill Cavanaugh wrote about this brilliantly in his essay “The World in a Wafer.” While there are new things to be said about globalization than he could have said in 1999, I think his main point holds. He writes:

In the organization of space…the Eucharist does not simply tell the story of a united human race, but brings to light barriers where they actually exist. When Paul discovers that the Corinthians are unworthily partaking of the Lord’s Supper because of the humiliation of the poor by the rich, Paul tells them, ‘Indeed there have to be factions among you, for only so will it be clear who among you are genuine’ (1 Cor 11:19). This verse is puzzling unless we consider that the Eucharist can be falsely told as that which unites Christians around the globe while in fact some live off of the hunger of others… In the North American context, many of our Eucharistic celebrations have been colonized by a banal consumerism and global sentimentality. The logic of globalization infects the liturgical life of the Church itself; Christ is betrayed again at every Eucharist. Where the body is not properly discerned, Paul reminds the Corinthians, consumption of the Eucharist can make you sick or kill you (1 Cor 11:30). This might explain the condition of some of our churches.

Cavanaugh goes on to give an altogether different example, that of Archbishop Oscar Romero. When one of his priests, Fr. Rutilio Grande, was gunned down, Romero proclaimed that on the next Sunday there would be only one mass celebrated in the whole diocese. “All the faithful, rich and poor, would be forced into a single space around the celebration of the Eucharist.” And in doing so, Romero collapsed the boundaries between rich and poor, but he also brought together the global and the local as a way of telling a different story than the one the Salvadorean government wanted to tell. Surely we, too, in our Eucharist, can also witness Christ’s story and not the one that is on current display in our culture.

- Finally, regarding the “nones” – much has been said about the nones as a rising force in American religion and what can be done about it. I have immense sympathy for the nones. Why bother belonging to a church when it often seems to function like a social club? Spirituality can, indeed be gotten in more wholesome ways than in a parish – especially when spirituality is about the relative calm and clarity of finding God in nature or in loving people without having to worry about the “rules” – over against dealing with the bitter bickering and cronyism that shows up in churches. And in the context of political parties, belonging to a party seems to have far more traction in contemporary culture than belonging to a church! But in relation to the point I make above – it strikes me that regardless of whether we “win back” the nones (anxiety about this seems to show up in every conversation about the nones, but I think that’s kind of beside the point of what Christians are about) – we’re far better off living with conviction about Jesus than we are trying to kowtow to whatever we think other people might want from us. (Because we’re likely to be wrong about what other people want – especially if we’re trying to “win” them back….) I’d rather be political about Jesus, in other words – and let the Republican, Democrat and whatever-else chips fall where they may.

Jana: Thank you for saying so well what desperately needs to be said. And thanks for returning my attention to Bill Cavanaugh’s essay. It’s worth noting that the word translated in 1 Cor 11:19 as “factions” or “divisions” is, in the original, “haireseis,” i.e. a heresy, from the root, “to choose,” as opposed to behaving and believing according to the whole: “kata holon,” as in “catholic.” What could be just a pedantic exercise in etymology deepens Bill’s point, I think, in that factionalism within the church almost always means choosing and absolutizing part of a truth. The sin of factionalism is not how badly and how often factions get things wrong, but how little of the totality of truth factions are willing to settle for. It’s simply impossible to compress the vastness of the gospel into even the entirety of those narrow spectrums defined by the poles of liberal and conservative, socialist and capitalist, or radical progressive and reactionary, much less in one camp.

As for the “nones,” one way to look at the history of Catholicism in the United States is through the lens of 1 and 2 Samuel and 1 and 2 Kings. Catholic immigrants wanted desperately to be like the other “nations” in that they wanted to be accepted as truly American. It took many long decades, but we’ve gotten our wish, and the absolutized partial truths over which our factions now fight wittingly or unwittingly envision Holy Mother State as the guarantor of Christian morality in abortion, gay marriage, welfare, and immigration. Dante, in Inferno, uses the word contrapasso to describe how the punishment for mortal sin is the sin itself, that God, in the end, gives those who will NOT accept God’s will what they want. Forgive the Augustinian spin on my reading of Dante, but getting the order of one’s loves wrong leads to intrinsically disordered loves, which leads to disordered persons, lives, communities, nations, and churches. That God can make good come from such chaos, I have no doubt. That our children can see that from our behavior is highly questionable.

These are just some quick thoughts in response to your wonderful piece. If anything here is helpful, feel free to use them. If not, you do well to ignore them.

Brian

Thanks Brian – I pretty much agree with what you’ve said, including the Augustinian spin on Dante! I don’t think we can narrate the nones in quite the context you’ve named here, though – since “nones” are not just about Catholics. But I still think the “Holy Mother State” piece is part of it, regardless of which part of the kingdom people hail from.

Jana: You are, of course, right that the “nones” can’t be narrated as a “Catholics in the US” phenomenon. I suppose I was narrating one version of the rise of once-Catholic nones in this country. Whether one sees the Church as primarily besieged, corrupt, accommodated, or decadent — and I suppose it’s all, though not only, these — it’s plain that many of our children find little that is compelling in the way our lives our shaped as a church. As you suggest, “winning back the nones” to a club that’s both fractious and boring is beside the point. We are called to live as a gathered Body into the mystery of Christ. What follows was never in our control anyway.

A final anecdote: A priest spoke to our parish about liturgy some years ago and pointed out that some Catholics — lay and ordained — perhaps wishing to make the “church experience” more welcoming, mistake themselves as hosts and not guests. The priest went on to say, “Christ is the host. You are one of the guests. If you ever start thinking of yourself as the host at liturgy, look around at all the other people and remember that if you were really the host, you wouldn’t have invited half of them.”