This post is part of a series. See Dana’s introduction to the series here, and Dana’s own post here. Last week Charlie contributed his post here. I’m humbled by the opportunity to join the conversation.

—–

I believe in God.

I believe in a God beyond gender, beyond naming, a God whose energy holds the moon in orbit and the stars in place… a God who is more “verb” than “noun” … and a God who is as close to me as the air I breathe. I believe in a God beyond human reason, who is nevertheless known through reason. A God beyond human history, who is nevertheless known in human history. A God beyond human language, about whom I continue to speak. I believe in a God who inspires deep compassion, who understands fairness and divine justice through a lens of mercy. A God who invites, and waits, and listens.

I believe that Jesus is the Son of God, that his earthly ministry modeled divine compassion and radical love. That Jesus came to share the good news that relationship with God was possible, and that one could demonstrate love for God best by living a life of love and service.

I believe in the Holy Spirit, present among us to bear witness to suffering, to inspire, to sustain, to challenge, to comfort us in our searching.

I believe in the church, community of saints and sinners. Discipleship of equals. Both product of and shaper of culture.

I believe that our planet is sacred, that human nature is precious though broken, that evil is real but not as strong or as enduring as good.

—–

A wise professor once told me that “all theology is autobiographical.” In the process of writing this, I’ve come to see how so many of my theological commitments are grounded in my experiences. Maybe my experiences will resonate with yours. Maybe not. One thing I do know is that faith is not a static thing set in stone but a dynamic process by which we come to more fully understand who we are, what life is all about, and how God holds and sustains us through the journey.

—–

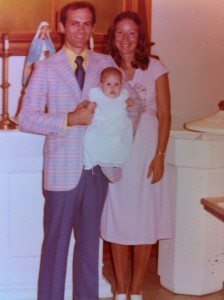

Summer, 1978.I was baptized into the Catholic Church in St. Lawrence Parish, Fairhope, Alabama. I’m that cute baby in the picture. My parents are beaming. On my baptism day, my parents and godparents promised to train me in the Catholic faith. They kept their promise. I grew up in a loving family and learned about the Christian life from some of the best teachers around: my parents, siblings, and friends.

Summer, 1978.I was baptized into the Catholic Church in St. Lawrence Parish, Fairhope, Alabama. I’m that cute baby in the picture. My parents are beaming. On my baptism day, my parents and godparents promised to train me in the Catholic faith. They kept their promise. I grew up in a loving family and learned about the Christian life from some of the best teachers around: my parents, siblings, and friends.

Memory, Second Grade, St. Ignatius Catholic School, Mobile, Alabama: Other moms brought cookies or helped with art projects. My mom, who played guitar and loved folk music and spiritual songs, used to come to my second grade classroom to teach us songs and play along with her guitar. Rise and Shine… And They’ll Know We Are Christians by our Love… His Banner Over Me is Love… Jesus Loves Me… Jesus Loves the Little Children… and silly songs like My Aunt Came Back… When it was time for our class to learn the Ten Commandments Song (“First, I must honor God…”) to sing at our First Communion, my Mom helped us learn it and practice it.

Memory, Fourth Grade, Easter. My siblings and I are dressed in coordinating outfits. I’m the oldest and I just turned old enough to find it embarrassing. My new white shoes are giving me blisters. Church is taking a long time. I want my chocolate Easter bunny. I’m grumpy. But the music is nice today. The choir has practiced their songs, and the songs seem happy, not like the last few weeks. The priest is wearing white and gold. There are trumpets. We never have trumpets. I think to myself, this isn’t so bad. No one will notice if I take my shoes off under the kneeler, and I can wait to eat my chocolate.

Memory, Eighth Grade. Our class is preparing for Confirmation, and we are told to think about how serious this is. Do we really believe it? Are we ready to be adults in the faith? The whole preparation kind of seemed like a series of hoops to jump through. I could trust Kit, so we talked about it, and I asked her, if I am not totally sure that the communion wafer is really Jesus’ body and the wine is Jesus’ blood, does that mean I shouldn’t be confirmed? But wouldn’t it be strange to skip it when everyone else is doing it? And my Mom already bought the dress. Were we supposed to be able to feel the Holy Spirit descend on us like a dove? Was it ok if I didn’t?

Memory, Summer 1993. World Youth Day. I’ve been excited about this trip for a long time. Sure, I’m as excited about crushes on boys, time with friends, and a long road trip as I am about seeing the pope. I’ve been involved in Youth Group at my parish and we travel by bus from Mobile, Alabama, to Denver, Colorado, and back. We see John Paul II in Mile High Stadium. Among the spiritual highlights of the trip was the night we were camping in the middle of a huge field with hundreds of other pilgrims. We met Catholics from all over the world. That night, I saw a shooting star.

Memory, 1995. My high school religion teacher is explaining that the Catholic Church is the one true church, and salvation is only possible through the church. Our only textbook was the Catechism. I’ve been attending Young Life meetings and Bible studies, and have developed friendships with the leaders, none of whom are Catholic. I think to myself, Are these holy, good people going to hell because they aren’t Catholic? It didn’t make sense to me. Jane was so generous, kind, compassionate, honest, funny. She was authentic. Jane met us at the Young Life office at 6:45 on Thursday mornings so that we could have a girls-only Bible study before school started. She spends her summer vacations with high school students leading Young Life camps. She taught me what it means to have a personal faith in Jesus. And she’s going to hell? Deep inside, a question.

Memory, 1996. There’s a rumor going around my high school campus that my favorite history teacher likes President Clinton and defended a Clinton policy in the other section of the class. I wish I had been there to hear it myself. I’m curious. At this stage in my life, politics and faith are not always easily separated. There is an easy marriage between Catholicism and conservative Republican family values, “Southern” values. I absorb this. I don’t question it. Honestly, I didn’t think that one could be Catholic and Democrat. I grew up in a loving environment, and also an insulated one. The only non-Catholics I knew were Baptists and Presbyterians and Methodists. Non-Christians were totally “other” to me. My experience of reality was filtered through my privilege in a way that I never recognized and certainly never interrogated. But I had great friends, and and we had a lot of fun together in our high school years and after.

Memory, 1997. What’s your major? At first I dreaded the question. I always had an interest in theology, but I grew very tired of people asking me if I wanted to be a priest. Many wondered aloud why a woman would want to study theology. After my first semester, I thought about declaring theology as my major, but trusted advisers from home, including our parish priest, youth ministers, and others I looked to as guides on my faith journey, warned me that the theology department at Notre Dame was liberal, and I was likely to lose my faith if I chose that path. Much better to study philosophy, they said. I ended up at a PLS (Program of Liberal Studies) major with a theology minor, and I do not regret that decision. I loved PLS. But I do think about the warnings I received, and my own fears about going off to college so far from home. The thing is, I did not lose my faith. But my faith was challenged in ways that I hadn’t anticipated. Not only in the classroom, but in little ways through friends and relationships and experiences outside the classroom. I went through different stages. There was a time when I craved certainty and rigidity, and I delighted in explaining official teachings on a range of issues. When I participated in mission trips or service projects, I felt God’s presence. I thought I was doing the right thing, that this service was part of what it mean to be a good Christian. I wanted to help people, and I wanted to learn more about my faith. There was a time when I preferred the social justice projects to prayer groups, when I would rather go to the Center for the Homeless than Mass.

Memory, 1998. There’s a chapel in my college dormitory, and I am one of the liturgical coordinators. I was drawn to Notre Dame for a lot of different reasons. Catholic. Solid academics. Snow in winter. I loved that there was a chapel in every dorm, and I had heard very good things about the campus ministry programs so I knew I could get involved with activities that would nourish my faith. At Cavanaugh Hall we baked our own bread for Eucharist, and residents pitched in as lectors, Eucharistic ministers, and musicians. The Prayers of the Faithful were always personal and meaningful. It was Mass, but it was homey and real. People actually sang. Praying together formed our community in a way that late night studying or partying couldn’t.

Memory, 1999. What will you do after graduation? For a time I dreaded the question. I wrestled with profound insecurities in high school and college. I had a difficult time figuring out what it meant to be a strong, self-reliant leader while also feminine and proud of my Southern heritage. It took being away from home, and with trusted friends from other places, to have the distance and safety of thinking critically about my upbringing; of course, there was a heavy trade-off there. By moving further away, it became more difficult to nurture relationships with family and friends back home. It was expensive to travel on breaks, and I was sorry that I missed many milestone moments in the lives of my younger siblings. When I did come home for breaks, we had all changed, and while I always had a good relationship with family members, we hadn’t seen the small steps of our changes, only the big jumps over time, so it became harder to understand each other. In some ways we grew apart, for a time. My grandfather told me everything would be ok as long as I didn’t fall in love with a Yankee. Paw-Paw, may he rest in peace. I am not sure if Paw Paw ever understood why Notre Dame was such a special place for me, or why it was good for me to move away from Mobile. I wrestled with what was expected of me as a woman. Should I feel guilty for not wanting to marry young and start a family right away? I experienced some culture shock in college, and that unsettled me. But I also think that it initiated deep learning and openness to new ideas as an undergrad. There was a freedom that came with being away from home. A freedom to explore new ideas. And yet I was frequently homesick and was very aware of what a privilege it was to attend an expensive university. Of course, it was the sacrifices of my parents that made my journey possible. My parents have always been patient with me, and they encouraged my graduate studies even if we didn’t know exactly where it would lead me. Family remains important to me, and even though my theological convictions might be different than those of my parents or siblings, we respect each other and want the best for each other. I feel very grateful for their love and support.

My travels, my relationships with friends from other parts of the country, my experiences studying abroad, and my journey in the history of ideas—through PLS and other courses in liberal arts, as well as my first encounter with the writings of theologians like Karl Rahner and Elizabeth Johnson– profoundly shifted my understanding of Catholicism. I am grateful for the college professors who nurtured my faith while also challenging me to think critically and to speak up more in class. In particular, I am grateful to Rev. Nicholas Ayo, C.S.C., who once told us that “the best chance of getting at the Truth is for everyone to talk.” Some of my biggest “aha” moments in college were in his classes, and he had a gift for using creative analogies to help students understand the material. I still have the notebook where I wrote down my favorite quotes from Fr. Ayo.

———-

My relationship with the Catholic Church has not been an easy one in my adult life. Lately it has felt more like the loud and confusing maze of Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride than the tranquil and happy boat ride of It’s a Small World.

It was at Weston that I had my real feminist awakening, although the seeds had been planted years before, and would be nurtured later at Loyola and USD. Growing up, God was male. Since we called God Father, it was natural to think of God as a male authority figure. But in my early twenties, this seemed wrong to me. Communion wafers weren’t the only part of the liturgy that seemed stale– the prayers, too, seemed limiting. It felt like Mass was the hoop I jumped through to avoid feeling guilty but my real prayers were my time spent with books that gave me permission to question, doubt, challenge. Sometimes it was theology, sometimes poetry.

I was at Weston when the Boston Globe’s investigative reporting uncovered story after story of the sexual abuse of minors by Catholic priests. I felt betrayed by the church. I was sad and angry. The bishops lost a lot of credibility in my mind. I lost trust in authorities. I became more suspicious of and critical of clericalism. At the same time, my faith was nurtured by Jesuit priests and scholastics at Weston, including my teachers, Rev. Jim Keenan, S.J., Rev. Ed Vacek, S.J., and my friends Jean-Baptiste Mazarati, John Thiede, and my community at the lay student housing. Had I been anywhere else while the clerical sex abuse crisis unfolded, I may have left the church for good. But I couldn’t give up on the church when my Weston friends wouldn’t give up on me. Solidarity with victims became primary for me. I was comfortable thinking of the church as a human institution. My God was bigger than my church. And I could approach my faith critically, asking feminist questions like: On what evidence do you base those theological claims? Who benefits from your construction of reality? Whose voices are at the table? Whose voices are missing? As I read more feminist theologians, and more newspapers, I had a growing awareness of the enormity and gravity of suffering in the world. And I feel so small in the face of it. I came to see with deeper clarity the intersecting injustices of race, class, and gender. I came to recognize my privileges with humility and gratitude, and a good deal of discomfort.

Having friends come out challenged me to rethink church teachings on homosexuality and gay marriage. I wanted to trust my church. I understood that church teachings have a presumption of truth. But I did not believe that Jesus was calling me to blind obedience of religious leaders. When I talked with gay friends, I realized that we shared some experiences of pain and confusion in our faith. Of feeling excluded at Mass, though for different reasons of course. I interned for one summer with the Los Angeles Ministry with Lesbian and Gay Catholics, led by Rev. Peter Liuzzi, O. Carm., and Marge Mayer. I really admired how they walked the tightrope of fidelity to church teaching while also welcoming and listening to the voices of lesbian and gay Catholics. We had a booth at the LA Pride Festival with a large banner reading “Welcome Home Gay Catholics!” Father Peter used to say that it gets messy in the middle, but that his job was to navigate that messy middle. I really admired the work they did and continue to do. But I came to see that I was not being called to parish ministry. I believed that my gifts would better serve the church if I worked in the academic side of theology instead of pastoral ministry. But I returned to Weston carrying the stories of the summer with me, thinking that if church leaders had been able to hear the stories I had heard, they might have to reconsider the teaching that a homosexual orientation is “intrinsically disordered.”

—–

I go back and forth in my prayer life between the apophatic and kataphatic traditions of spirituality. Sometimes I lean towards the apophatic, the way of negation, the encounter with God through silence. I admit that this is my most difficult practice: to slow down all of the conversations in my head long enough to just sit in the presence of God is a real challenge and takes work. There are some times in my life when I long for this kind of prayer, which this is the only kind of prayer I can pray, when words don’t work and images don’t work and I just need to cut through the bullshit and sit with God.

But my more everyday, realistic approach to prayer is the Ignatian mantra of God-in-all-things. I think about the sacramentality of everyday life. God’s call to service as I fold laundry or make dinner. Knowing the God of creation as I savor a sunset or take my daughters for a walk. Remembering the waters of baptism as the girls are in the bathtub.I am most in touch with God, most attuned to the presence of the Holy Spirit, when I am awake enough to be fully in the present, the here-and-now beauty of little moments that have their own transcendence. Lately, I feel closest to God when rocking my infant daughter to sleep. But before having kids, I felt close to God when walking the dog, jamming to a great song, reading a provocative theological text that helped me to wake up to the presence of God.

—–

It helps, sometimes, to take the long view. When viewed in the context of the history of the planet, my religion is relatively recent. When hiking in northern California I saw a tree older than Christianity. Think of the age of the stars and it boggles the mind.

Nevertheless, I grow impatient. I thirst for justice. I have an activist spirit, and grow impatient with the academy sometimes. I wonder if I should have been a social worker, or worked in direct service to the poor through an NGO or charity. But the truth is that I love my job. Accompanying students in their spiritual growth through the college years is a privilege, and theology conferences make me feel like I’m in the “inner circle” of church work, even if we get bogged down in certain ivory-tower sort of discussions sometimes.

Why do I do what I do? Because I still have questions, because theology is more of a journey than a destination. And because it is not a solitary venture but one done in a community of faith where we learn from each other.

As a teacher, I try to honor where students are in their own faith journey. I try to help students understand that they are beloved of God, no matter what. I try to choose texts that inspire them. I ask them what rings true for them and why. I think it is better if I avoid offering simplistic answers to complex questions. I think it is better for me to say I don’t know.

And the truth is, there is a lot I don’t know.

Here is where I stand, in the big tent of the Catholic Christian tradition. It is a tent big enough for both Christopher West and Andrew Sullivan, for John F. Kennedy and Dorothy Day, for Paw Paw and me. Don’t get me wrong. I know why people leave the church. I still struggle with the exclusively male language we use for God at Mass. I wonder how my daughters will come to understand their identity as Christians if this is the way we form their theological imagination in liturgy. But I also think that if you leave the Catholic Church in search of a perfect community of faith, you won’t find one. So while I know that my faith community is not perfect, and I have a list of concerns, still the Catholic Church is my spiritual and religious home. Leigh’s baptism (see picture), was at St. Lawrence Catholic Church in Fairhope, Alabama. Same parish where I was baptized. Now Leigh is three years old, and she loves to dance. We sing all of those songs that my mom sang with us growing up. Last night she wanted me to sing This Little Light of Mine before bedtime. Lately her favorite song is Lord of the Dance. Seems a fitting end for this post. I love the image of God dancing, of Jesus inviting all of us in to a big cosmic dance party. Cue the music:

Here is where I stand, in the big tent of the Catholic Christian tradition. It is a tent big enough for both Christopher West and Andrew Sullivan, for John F. Kennedy and Dorothy Day, for Paw Paw and me. Don’t get me wrong. I know why people leave the church. I still struggle with the exclusively male language we use for God at Mass. I wonder how my daughters will come to understand their identity as Christians if this is the way we form their theological imagination in liturgy. But I also think that if you leave the Catholic Church in search of a perfect community of faith, you won’t find one. So while I know that my faith community is not perfect, and I have a list of concerns, still the Catholic Church is my spiritual and religious home. Leigh’s baptism (see picture), was at St. Lawrence Catholic Church in Fairhope, Alabama. Same parish where I was baptized. Now Leigh is three years old, and she loves to dance. We sing all of those songs that my mom sang with us growing up. Last night she wanted me to sing This Little Light of Mine before bedtime. Lately her favorite song is Lord of the Dance. Seems a fitting end for this post. I love the image of God dancing, of Jesus inviting all of us in to a big cosmic dance party. Cue the music:

I’ll live in you if you’ll live in me

I am the Lord of the dance, said heDance, dance, wherever you may be

I am the lord of the dance, said he

And I’ll lead you all, wherever you may be

And I’ll lead you all in the dance, said he

Emily, thank you for your vulnerability and willingness to share your story with all of us.

Wow Emily, what a beautiful post. Incredible. Your best yet that I have read. One of many things that popped out at me were your words…

“Sometimes I lean towards the apophatic, the way of negation, the encounter with God through silence. I admit that this is my most difficult practice: to slow down all of the conversations in my head long enough to just sit in the presence of God is a real challenge and takes work.”

You’ve opened a door here which deserves an entire forum of it’s own. I do wish I could help make that happen, here or elsewhere. This is the Catholicism I hope to learn more about.

As I experience it, in every moment we face a choice between two realms.

1) There is the symbolic world within our minds, which we rule over as petty gods.

2) And there is the real world, ruled over by the real God.

As you wisely share, it can be difficult indeed to give up our little throne, even for a few moments. And yet when we are able to do so, we discover the real world that God rules over is immeasurably more impressive and fulfilling.

It seems God is quite the polite fellow, and he declines to interrupt us while we are speaking, preferring to wait patiently for us to finish our so many internal remarks before he has his say. He often has to wait quite awhile, given our fascination with ruling over our internal symbolic kingdom.

For excessively energetic thinkers such as myself and those assembled here, theology may eventually come to be seen not as the path to God, but as the primary obstacle which must be overcome for the real inquiry to begin. This is perhaps most likely to happen just at that moment when we feel we’re beginning to master theology, revealing God to be not only patient and polite, but a bit of a practical joker as well.

God is enjoying a laugh at my expense right now, as he knows I’d like nothing more than to think and type about this endlessly fascinating subject every moment for the rest of my life, thus utterly demolishing the very point I so hope to share. The little internal symbolic kingdom I rule over is a foolish one indeed, and a sense of humor my only salvation.

Emily– Really beautiful, intricate, and helpful. I am glad you told this story, and I think it is a really powerful testimony, one that in particular my conservative students do not understand… and should. Thank you for giving me a narrative that can help them see faith in better, more varied forms!

“…if church leaders had been able to hear the stories I had heard, they might have to reconsider the teaching that a homosexual orientation is ‘intrinsically disordered.'”

Actually, the Catholic teaching is that the orientation is objectively disordered. That is a very different thing indeed from being intrinsically disordered.

In rereading this excellent post, I came upon another gem…

“That Jesus came to share the good news that relationship with God was possible, and that one could demonstrate love for God best by living a life of love and service.”

All that ails the Church could be healed if Catholic doctrine was boiled down to this one sentence.

When we finally find our way to welcoming women to lead us, such miracles shall unfold.

Theologians might reflect upon the assertion “thought is inherently divisive”. That is, the fundamental nature of thought is to divide, just as the noun divides one part of reality from the whole.

If this is true, then the construction of ideologies and beliefs, the process of theology, is a fascinating but ultimately doomed effort. Whatever we might make out of an inherently divisive medium will lead to division and conflict. As evidence, no philosophy in history has succeeded in uniting human beings and bringing peace. Every ideology has divided people from one another, both externally and internally.

We need women leaders to help us move Christianity out of our heads, and in to our hearts. And then from our hearts, out in to the world, expressed as love in action, ie. service.

However, this is perhaps too ambitious to be realistic, so…

If the moderators allow, in coming weeks I will offer a specific concrete opportunity to both keep our cherished talking of the talk (yes, I love it too), while converting it in to the walking of the walk as well.

Thank you, Holly, David, and Phil, for your kind praise.

Of course, there is more to my story but I was well beyond the suggested word limit when I hit “publish”– so I will spare you the details of the rest!

Phil, I’m interested in how you propose that we move beyond the natural divisiveness you describe. I appreciated your comment about the challenge of understanding the symbolic/real as distinct realities, but I think I am more optimistic than you. I do think we often have problems with perception, and interpretation of reality. But my answer, similar to my teacher’s, is for more people to talk. If more people get into the conversation, sharing their own perceptions/experiences, limited though they are, then we will have a more complete–though always still incomplete–picture of the faithful’s grasp of the living God. What do you think? In the end, I fear that if we go down the path you describe, we diminish the role of theology for the life of the church.

Paccer, we are both right. My language came from an earlier document, but you see in this quotation that both are used in On the Pastoral Care of Homosexual Persons:

Explicit treatment of the problem was given in this Congregation’s “Declaration on Certain Questions Concerning Sexual Ethics” of December 29, 1975. That document stressed the duty of trying to understand the homosexual condition and noted that culpability for homosexual acts should only be judged with prudence. At the same time the Congregation took note of the distinction commonly drawn between the homosexual condition or tendency and individual homosexual actions. These were described as deprived of their essential and indispensable finality, as being “intrinsically disordered”, and able in no case to be approved of (cf. n. 8, $4).

In the discussion which followed the publication of the Declaration, however, an overly benign interpretation was given to the homosexual condition itself, some going so far as to call it neutral, or even good. Although the particular inclination of the homosexual person is not a sin, it is a more or less strong tendency ordered toward an intrinsic moral evil; and thus the inclination itself must be seen as an objective disorder.

http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_19861001_homosexual-persons_en.html

Emily Reimer-Barry: “…if church leaders had been able to hear the stories I had heard, they might have to reconsider the teaching that a homosexual orientation is ‘intrinsically disordered.'”

paccer (Paul Connors): “Actually, the Catholic teaching is that the orientation is objectively disordered. That is a very different thing indeed from being intrinsically disordered.”

Emily Reimer-Barry: “Paccer, we are both right. [Quotation]”

No. You quoted two paragraphs from On the Pastoral Care of Homosexual Persons. The second paragraph only points out that the inclination is an objective disorder. And the first paragraph only refers back to a prior document, Declaration on Certain Questions Concerning Sexual Ethics, which only says that homosexual acts are intrinsically disordered, not the inclination or orientation. (Also, because the first paragraph you quote only refers back to the text of a prior document, the word ‘These’ at the end of the first paragraph can only refer to “homosexual actions” and not also to the “condition or tendency”, since that is what the relevant parts of that prior document say.)

In case it seems to the perhaps three people left reading these comments that we are engaged in a minor nit-picking exercise, any false conclusion about what is intrinsic to humans will necessarily, step by step, affect all the teaching about who God is, whether He is good, the whole relationship between God and humans, and all actions between humans themselves. Ex falso quodlibet.

Emily, I hope you will abuse the suggested word limit 🙂 again sometime soon, as I enjoyed your comments and look forward to doing so again.

Again, I believe your question regarding moving beyond divisiveness is quite well answered with your own simple words…

“…and that one could demonstrate love for God best by living a life of love and service.”

I agree, and am optimistic that the experience of love and it’s expression in action, the walking of the walk, is sufficient unto itself.

If we can find sufficient faith in love, which is most likely to come by practicing it in action, I believe we’ll find ever less need for the ideologies which inevitably divide us.

I must admit that I’m not that troubled by diminishing the role of theology in the Church, and I honestly believe more talk will lead mostly to more division. I spent months building a free publishing network for Catholics, only to dismantle it upon that quite inconvenient realization. One lives, one learns.

How about we replace the passion for theology with a practical discussion of how to raise more money for Catholic Charities? Such a shift of focus would seem to be in line with your wise words quoted above.

However, honestly observing my own addiction to the glorious talking of the talk, talk, talk, I have to realistically recognize that the inherently divisive experience of ideology will be with us for some time to come. Given that, my hope now is to put the talking of the talk to work feeding the hungry etc.

So, in absurd summary, theology is bad, and I hope you’ll be sharing more soon. 🙂

Emily, you said…

“Paccer, we are both right.”

Apologies, but neither of you are right.

Homosexuality is not a “problem” that needs to be analyzed, solved or judged.

Sadly, Church documents on this particular subject are of no value whatsoever. Oh well, nobody’s perfect.

Homosexuals wish to fall in love, get married, and raise children for exactly the same reasons we do.

We are locked in battle with the gay community in the hopes of preventing them from doing the very thing we’ve been endlessly preaching to be the ideal.

That’s what’s disordered.

Not them.

Us.

Paccer, I see your point. I was imprecise in my post, and should have said that church leaders might have to reconsider the teaching that homosexual actions are intrinsically disordered, as well as the teaching that a homosexual orientation is objectively disordered. You say it is not a nit-picking exercise. I will let other readers come to their own conclusions about that. But my underlying point (after all, this was a minor point in my post) is that church teaching on homosexuality remains painful for many Catholics, including gay and lesbian Catholics, their parents, and their friends. Phil’s comment, and turning of the tables on what is considered “disordered” is a sentiment I hear often among both my students and friends. OLPCHP is right that an overly benign interpretation of the homosexual orientation has become widely accepted, some Catholics saying even that the orientation itself is good or neutral. I think this debate continues, and as the church continues to seek truth together, the voices of lesbian and gay Catholics need to be at the center of the conversation.

Emily, it is because I agree so strongly with your point “that one could demonstrate love for God best by living a life of love and service” that I replied to the homosexuality issue. I believe the two things are directly related.

Imho, the homosexuality issue is a real world God given test of whether we are willing to elevate love above ideology.

The gay community, a traditional victim group, is asking the dominant culture to provide tangible evidence that a pattern of oppression that’s been underway for centuries is finally really over.

Catholic ideology suggests we decline this request, Catholic love suggests we grant it.

Long suffering innocent victims are reaching out to us, and telling us what will ease their pain. How will we reply? Is our reply about us and our needs, or is our reply about them and their needs?

I see lots of well meaning Catholics searching for some kind of compromise middle ground. I don’t believe such a place exists in regards to this issue.

We say yes to this request, or we say no. We choose love, or we choose ideology.

It’s a simple, if not easy, choice that should tell us a lot about what our theology really is.

We say yes to this request, or we say no. We choose love, or we choose ideology.

Phil, What if homosexual acts are sinful? Then your ‘love’ helps foster another’s potential damnation and it cannot be a reflection of God’s love. Simplistic formulations lead to simplistic answers

Bruce, in all the well funded raging controversy on this topic, we’ve yet to see even a single specific individual person sue their state for damages caused by gay marriage, let alone win their case in court.

On the other hand, we have a well documented and widely agreed upon history of unjust oppression of many millions of peaceful innocent gay people going back centuries.

Are you sure you wish to start a discussion about sin?

Phil, you aren’t being challenged to defend what you are apparently ready to to defend. You are being challenged on your argument that “all you need is love” and no theology or even thinking. Bruce is pressing the point that this seems unlikely to be true. Different understandings of what counts as good for another must be hashed out because one can agree that what one has for another is actually love. It would be helpful to have an answer to the challenge Bruce made to your “all you need is love” position.

So we return now to digging in the gold mine of Emily’s article, uncovering the next gem…

She said, “I believe in … a God who is as close to me as the air I breathe. I believe in a God beyond human reason, who is nevertheless known through reason.”

To me, this passage raises the question of whether “God” and “me” are really two different things, or whether the separation implied by the use of two different words is more an illusion created by the inherently divisive nature of thought.

While philosophy/theology invests a great deal of investigation in to the content of thought, with a focus upon comparing this idea to that idea, perhaps a more productive inquiry would move up a level to a closer examination of what all ideas are made of, thought itself.

As example, imagine that we are wearing pink tinted sunglasses. Everywhere we go, whatever we observe, it appears to be some shade of pink.

If we don’t understand the properties of these glasses and the distortions they introduce in to our observation, we could spend centuries pointlessly debating which shade of pink is the best.

What if thought is inherently divisive, and so everywhere we look we perceive a separation between “me” and “everything else”, an experience which generates a profound sense of isolation leading to pain and fear, and all the other psychological maladies which so afflict us?

What if this separation is not real, but an illusion introduced by the limitations of thought, the equipment we are using to make our observation?

Emily tells us God is as close to her as the air she breathes. What if “God”, “Emily” and “air” are only separate things in the conceptual realm, but not in the real world?

If this is true, then it would seem to follow that any attempt to heal the apparent separation through the use of thought, reason, ideology etc is likely to fuel the illusion of separation instead of remedy it.

Is an inherently divisive medium the best tool for seeking reunion with God?

Charles, because of the format of this software it seems I have to place what must be a lengthy reply to you here in the broader column. I hope that’s ok. If not, please advise.

I don’t read Bruce’s comment as you do, but ok, I’m happy to accept and respond to your interpretation of his remarks, an interpretation which I agree opens many interesting cans of worms. I would enjoy nothing more than to explore such issues at length.

As a place to start, perhaps we can agree that the best minds among us have been searching for centuries for an ideology that would unite humanity and bring peace.

My argument is that they have not succeeded.

As evidence, I offer as just one example Christianity, a very sincere and powerful ideology explicitly about peace, which after 2,000 years is still in a state of perpetual conflict with itself.

The same can be said of other ideologies and philosophies, all which seem to inevitably divide people against one another, both within and without the ideology.

I argue that this failure to find a unifying ideology of peace can not be explained by a lack of effort or ability by those involved in the inquiry, given the extraordinary talents involved in what is arguably the most significant undertaking in human history.

I argue that if the problem was with the content of ideology, we would have found the correct ideological content by now, and we would currently be experiencing the unity and peace we seek.

This line of reasoning leads me to shift the inquiry up a level from the content of ideologies, to a closer examination of what all ideologies share, what they are all made of, thought.

If the problem is found at this level, in the properties of thought itself, the search for the perfect ideology which brings unity and peace may be doomed to eternal failure.

I can not prove this to be true of course, I’m just offering it as a hopefully productive premise to be investigated and challenged etc.

If it should be true that philosophy is an endless merry-go-round to where we already are, then what?

Emily has referenced two powerful alternatives to ideology in her post above, which is why I’m so interested in what she has to say.

1) She has suggested “one could demonstrate love for God best by living a life of love and service.”

1) She has also spoke of the act of listening to God.

Both service and listening are acts of surrender. Neither are about us. And so I believe both approaches might be fairly described by the expression “die to be reborn”.

In contrast, we might observe that ideology usually comes in the form of “my ideology”. My position, my beliefs, my argument, my ideology, my rhetorical triumph and so on.

My triumphant argument 🙂 is that because ideology is made of the inherently divisive medium of thought, it tends to feed the illusion of a separate “me” which I see to be the fundamental human problem which brought us to religion in the first place.

I’m not against thought or theology. I’m for following both through to their logical conclusion, which appears to me to be a deeper understanding of the limits thought and theology.

If I had even the slightest talent for conciseness, I might have suggested instead that we replace Catholic theology with a practical discussion of how to raise more money for Catholic Charities and similar service projects.

When I’m not here with you, this is what I’m working on, creating a mechanism for converting the talking of the talk in to the walking of the walk. With your permission, more on that in coming weeks…

As you can see, I have hardly escaped my own personal addiction to thought, so please share your response, as I am most sincerely interested in what you might wish to say.

PS: In rereading my post, I see there’s no reason to take seriously any commentator who can’t count to two. 🙂

Phil,

The somewhat obtuse point of my earlier post was that love demands action. Ideology is not an action but a system of ideas. My rough translation of your formulation is something like “We choose action or we choose ideas”. My question is smaller: What action? Doesn’t that action (genuine love) depend on what is best for the other? And what is best for the other may not be what they are requesting. One simple formulation like the Our Father, states it depends on the Father’s “…will be(ing) done on earth as it is in heaven…” Not human will but God’s will. His will (His love, His peace) is something which all humanity finds difficult to discern and perhaps even more difficult to implement, as your later post suggests. I mentioned sin because it opposes God’s love, so if a behavior is sinful, by definition, we know that it cannot be genuine love. I think determining the morality of a behavior helps us to understand whether our actions are truly loving or not. And I have not found my innate proclivities or feelings to be a reliable judge of sinful behaviors. I find it much more difficult.

Bruce, thank you, I understand your perspective much better now. My last reading of your remarks was likely too hasty.

In reply, I would suggest the following, offered in the context of the example we’ve both referenced.

Our gay friends and neighbors appear to be pretty intelligent, as is evidenced by the fact that they are currently trouncing the Church, no dummy itself, in the court of public opinion.

I suggest our gay neighbors are qualified to read the Bible and come to their own understandings, just as we do. If they should conclude homosexual acts are a sin, they are free to choose a life of celibacy, as some have already done.

Imagine if you will that some other group had a religious belief that Catholics should not marry each other, and they were seeking to use the force of law to impose this upon us. Would we consider that love?

Do unto others, as we would have them do unto us. Civilization requires that we not demand rights for ourselves that we are not willing to extend to our neighbors as well.

Phil, your analogy about Catholics marrying is not apt. Religion is not the battleground in the gay marriage debate though it certainly informs some peoples opinions. A more appropriate analogy might be disallowing men and women from marrying one person of the opposite sex. And frankly it wouldnt really matter if a law disallowed heterosexual marriage because men and women have the inherent ability to come together, procreate children and become a family. Gays cannot do this without the outside force of government allowing adoption, and/or the help of a third party through surrogacy.

However, I think your response still begs the question. What actions should I, Bruce, take if I believe that homosexual sex is sinful? I submit that your Do unto others, is really just a recipe to do nothing and is the opposite of love if I truly believe their homosexual behavior is sinful. Further, because humans are social, no ones actions, even in the privacy of their own home, only impact themselves. Even our private actions affect our subsequent behaviors and speech which impacts those we meet. So it is not only unfair to the homosexuals but the rest of humanity to do nothing. Also, public opinion is not a reliable guide to appropriate behavior; one example would be the forced internment of Americans of Japanese descent during WWII.

The question of gay marriage requires much more thought than many have expended.

Charles, now that I have responded at length to your entirely reasonable and quite relevant challenge to my remarks, I’m hoping we might hear your reply as well.

What might you add to my post above which begins with “Charles, because of the format of this software…”?

I was sincere in stating I’d be interested in learning how a person of your advanced training might regard such reflections on the nature of ideology and thought etc… That’s why I’m here.

Thanks!