Twenty-fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time

IS 50:5-9A

PS 116:1-2, 3-4, 5-6, 8-9

JAS 2:14-18

MK 8:27-35

Many of us go to church seeking to be saved. Some seek to be saved from the uncertainties of the world. Some want to be saved from a life that seems hollow or even meaningless. Some go to be saved from loneliness, or from their fear of death. Some go to be saved from a past marked by sin and regret. This impulse is not entirely wrong. To know that we are incomplete without God, to know that we are finite and broken is to know the truth about ourselves. In turning to God and to Jesus Christ we have come to the right place. As the many stories of Jesus forgiving sinners, curing the lame and the mute and the blind, and dining with outcasts attest, this is a God of mercy and compassion. At the same time, there is something else going on in the gospels. Jesus brings love and mercy, but also calls people to conversion. Jesus calls us to act. “Whoever wishes to come after me must deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me. For whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake and that of the gospel will save it.”

This Sunday’s second reading takes up the question of the relationship between our faith and our actions. The relationship between faith and works has been a source of serious controversy among Christians – especially at the time of the Protestant reformations. When thinking about faith and works there is a tendency to make two mistakes. The first (more typical among Catholics) is to think about good works as a way of earning our way into heaven. Many good things can result from intentionally going about doing good works. Theories of moral action and habituation tell us that by trying to grow in virtue and holiness through consciously and repeatedly doing good things we can reshape our character in positive ways. That is to say that by engaging in acts of generosity, or compassion, or courage we can grow to be people who are more generous or compassionate or courageous. We can grow in virtue, but that is not the same thing as earning salvation. There is nothing we can do to merit the gift of God’s love or the grace of salvation.

The second mistake is to claim that works do not matter. Since we’re sinful creatures who can never be perfect, and since there is nothing we can do to save ourselves, some people (more typically Protestant Christians) conclude that works and deeds are irrelevant. Christianity is reduced to a choice of whether to turn to God in faith or to turn away. This approach completely neglects the imperative to take up one’s cross and follow Jesus.

We can see the connection between God’s mercy and the call to act, and also begin to move beyond these dead-end ways of thinking about faith and works by putting all of this into the context of a relationship of love. When we come to God and Christ in our brokenness, what we encounter is mercy and an invitation to relationship. We are called to fall in love with God. Our experience of God’s love, and our growing love for and devotion to God is what should move us ultimately to act. We come to be so grateful for God’s love and so deeply devoted to God that there isn’t anything we wouldn’t do out of that love. We experience something similar when we love other people deeply. If we are lucky, there are people in our lives who we love so much that we would do anything for them – even lay down our own lives if it came to that.

Honestly I think many of us have forgotten about the centrality of love of God for our faith. That insight is missing from the way many Catholics (including me most of the time!) think about what it means to be Catholic. We think of our faith in terms of doctrines or in terms of a code of conduct or a call to social justice. We define ourselves by our refusal to use artificial contraception, or by our opposition to abortion, or by our unfailing commitment to the common good and we forget that all of these things should be expressions of our love and devotion to God, not substitutes for that relationship.

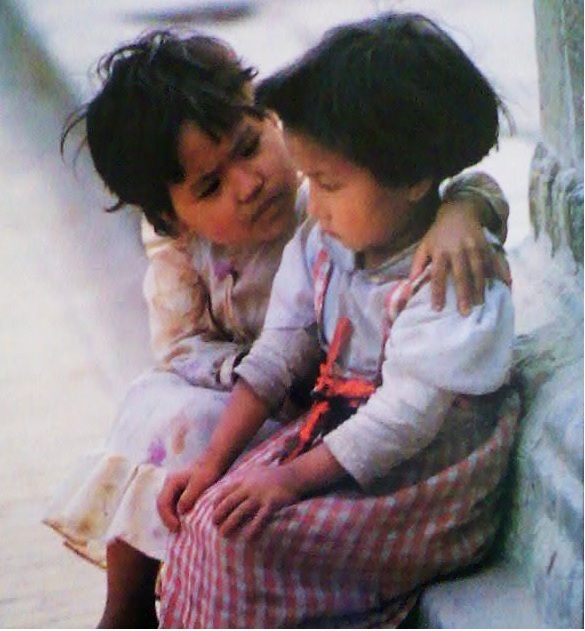

With Pope Francis’s visit to the United States fast approaching the speculation has begun to swirl: what will he say? What policies will he advocate before Congress? What will he say about the refugee crisis at the UN? Will he be “effective” in campaigning for real action on climate change? All of these questions are interesting and important, but if they are all we ask, we are in some ways missing the point. Pope Francis is working hard to call the church and indeed the world to a new attentiveness to the marginalized – to the poor, to the refugee, to the unborn – but he is doing so always in the context of a renewed call to faith. There is a certain superficiality about the lives that many of us lead today. That superficiality is sometimes obvious, in our obsession with technology, celebrity, and wealth for example. But there is a more important dimension of superficiality that we might find in our own hearts even after we have simplified , and advocated for justice, and acted in many other virtuous ways. It is a way of life that neglects God and love. Francis asks us to think about whether the beliefs that cross our lips and the actions in which we engage have a rootedness in a deep love for God. Faith without works is dead, but (at least for Christians) so are works without faith.

Nice post Christopher, great topic!

We might learn more about the relationship between works (ie. love) and faith (ie. belief) by observing how love and belief manifest in the world around us. When we observe what actually happens, what we see is…

1) Beliefs tend to divide us, even within belief systems explicitly about bringing people together.

2) Love tends to unite us, even when our beliefs are entirely different.

Why is this? Why does love unite while beliefs divide?

Perhaps John provides the answer when he says “God is love”. Let’s note carefully the words John chooses. God _is_ Love.

Perhaps love unites not because it comes from a higher source, but because it _is_ the Higher Source as John suggests?

And what are beliefs? Words and ideas in human beings about love and God. Well meaning and sincere most of the time, but from a far inferior source, the mind of man.

The relationship between love and belief is like the relationship between ourselves, and our name. We are real, while our name is merely a symbol. Only God can create us, while all we can create is our name. Love expressed in works is real, beliefs are just talk.

Works seem the most authentic form of faith, for they worship what God actually is, love, instead of just what somebody thinks or says about God, beliefs.