Readings: Ex 16:2-4, 12-15; Ps 78:3-4, 23-24, 25, 54; Eph 4:17, 20-24; Jn 6:24-35

I’ve spent this first week of classes preparing my students for an in-depth study of the Gospel of Luke, and this week in particular is the one I’ve dubbed my “anti-Marcionism” week. By which I mean, I want my students to understand the unity of the two Testaments, to understand that these gospel narratives only make sense with the full history of Israel behind them. I am making it my mission, even in this introductory course, to combat the common perceptions of the Old Testament as irrelevant accounts of an angry God that has been superseded by the God of mercy and love in the New Testament.

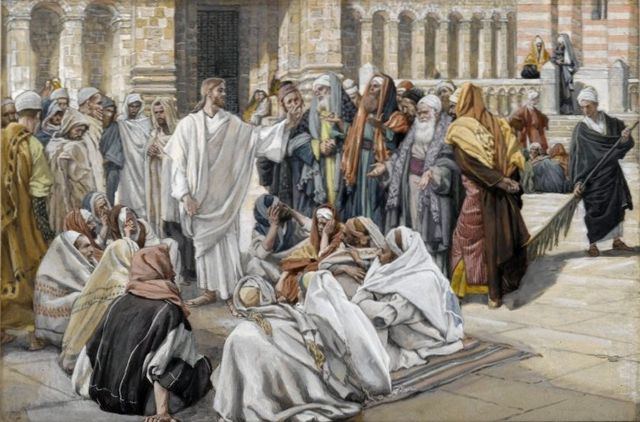

And then these readings came across my writing schedule, and I found myself a bit stumped. All too often in preaching, this week’s gospel is taken in a supersessionist, if not outright anti-semitic direction. This text is one of the reasons the term “Pharisaical” gets used as a derogatory term in moral theology — an entirely unjust picture, as the heart of the Pharisee’s project of interpretation was an approach to their scripture and tradition that was living, dynamic, and inclusive, rather than restrictive and legalistic. Part of what set the Pharisees apart from the priestly class, the Sadducees, was that they saw the authority to engage and interpret scripture as open to all, not the priests alone. Taken by itself, this gospel text makes them seem narrow-minded and exclusionary, when quite the opposite was true.

At the same time, there is no doubt that Jesus’s harsh words resonate in this moment in the Church’s life: “This people honors me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me.” These are words that many in the Church want to speak to the many bishops and priests that have been implemented in sexual abuse crisis and cover-up: men who by all appearances cared about the law of the Church, and yet failed to fulfill it. And when Jesus gathers the crowd to say:

Hear me, all of you, and understand.

Nothing that enters one from outside can defile that person;

but the things that come out from within are what defile.

“From within people, from their hearts,

come evil thoughts, unchastity, theft, murder,

adultery, greed, malice, deceit,

licentiousness, envy, blasphemy, arrogance, folly.

All these evils come from within and they defile.

Do we not want to shout — yes, yes to this! These evils have come from within and they have defiled our church.

It may be helpful, then, to remember that Mark wrote this Gospel in close proximity to the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem, a trauma that not only reshaped Jewish identity, but also shaped Christian identity. It was the destruction of the temple that eventually forced the small Jewish sect known as “Christians,” increasingly populated by gentiles, to define themselves as something distinct from Second Temple Judaism. Mark writes to a Christian audience that was still unsure of its identity in the wake of trauma. And here we sit, in the midst of another traumatic moment, many of us questioning our identity: as Catholics specifically, or maybe as Christians more generally.

It may be that we actually have a great deal to learn from the Pharisees, and the way they opened up tradition and interpretation (and in that sense, a form of leadership) to a wider, more lay audience. In fact, it is good for us to remember that Jesus is not condemning the Pharisees: in fact, by engaging them in argument, he participates in their project. Jesus was very much engaged in the rabbinical debates of his time, and when he pronounces a judgement, that judgment is informed and shaped by the debates that preceded him.

Perhaps, as we wrestle with the identity of the church today, we may contemplate the possibilities that deeper involvement of laypersons could offer. Our insular leadership has drastically failed us – in this moment, we ought to read Jesus’s words of chastisement not as directed at some distant “other” (the Pharisees), but rather at the heart of our own community, our own Church, today.