Leviticus 19:1—2, 17—18

Psalm 103

I Corinthians 3:16—23

Matthew 5:38—48

Perhaps the most well-known ethical precept of the Christian faith, besides the so-called “golden rule,” is the twofold command to “love the Lord your God with all you heart, mind, soul and strength and to love your neighbor as yourself.” We hear in the first reading for this Sunday the portion of the Mosaic Law where the second part of this love command originates. The selected passage is careful to include the covenantal context of the mitzvah to “love your neighbor as yourself”: it is but one of the many ways in which Israel is called to “be holy, for I, the LORD, your God, am holy.” To be holy—kodesh—is to be different, separate, “set apart from the nations.” That one should not bear hatred in one’s heart for one’s brother or sister, that one should “take no revenge and cherish no grudge” against any of one’s people, is meant to be the basis for creating a community that stands out from the human status quo. However much we may wish to presume that universal benevolence is the default posture between human beings, this covenantal mandate seems to suggest otherwise. Such benevolence must be the subject of a command. Yet such pessimism is more than balanced by God’s saving plan for humanity, which is to be brought about through Israel. Through Israel, God makes it known that we are not meant to be occasions of sin to one another. The antagonism we bear toward one another—in the home, on the street, in the marketplace—is not part of God’s plan from the beginning. The all-against-all of the “state of nature” is our own doing, our own invention.

To foreswear retaliation and resentment, however quotidian and petty, gives rise to a way of life that is at odds with “the world.” That is why St. Paul exhorts any among his Corinthian audience who fancies himself “wise in this age” to “become a fool, so as to become wise. For the wisdom of this world is foolishness in the eyes of God.” Just as in Leviticus, the ethical pretext for this particular directive is the call to share in the holiness of God. “Do you not know that you are the temple of God,” he writes, “and that the Spirit of God dwells in you? If anyone destroys God’s temple, God will destroy that person; for the temple of God, which you are, is holy.”

Though one could discern in this passage merely a divine threat, I contend that the more theologically consistent reading would yield a simple categorical claim about the nature of existence. If God’s holiness characterizes “the way the world really is” at its core, and if we have been made bearers of the divine image—“temples,” as St. Paul says—so as to steward the world toward conformity with this holiness, then to veer away from this holiness is ultimately to orient oneself to a “non-world,” a realm of self-destructive alienation.

This sort of self-destruction is precisely what God intends to save us from: “He redeems your life from destruction” proclaims Psalm 103, “crowns you with kindness and compassion.” This work of salvation has been underway since the exile from Eden and has made its general meaning clear in the liberation of Israel from Egypt. The concrete blueprint for the way of life associated with this salvation was given in the Law of Moses and has been ultimately brought to perfection through the Paschal mystery and the descent of the Holy Spirit.

St. Paul’s point in the epistle is that those who now live according to the Spirit are very likely going to be regarded as foolish by those considered “wise” in the eyes of the world. Again and again, Paul disparages worldly wisdom in his letters, not so much because it competes with his own message but rather because it presumes a fundamental paradigm of conflict and competition. Wisdom is, in a sense, a “contact sport” in ancient Greek culture: philosophers would contend with one another before an audience with their public standing at stake. (Indeed, the upper echelons of academic discourse operate this way even today.) In the world’s eyes, wisdom is necessarily a scarce commodity, an attribute acquired only at the cost of differentiation from others. Worldly wisdom is thus a “contrastive” good, one whose manifestation always depends upon competition and distinction from inferiors. Put more colloquially, worldly wisdom is built upon “boasting,” upon the comparison of this human being and that human being. But “let no one boast about human beings,” writes St. Paul, for “all belong to you, and you to Christ, and Christ to God.”

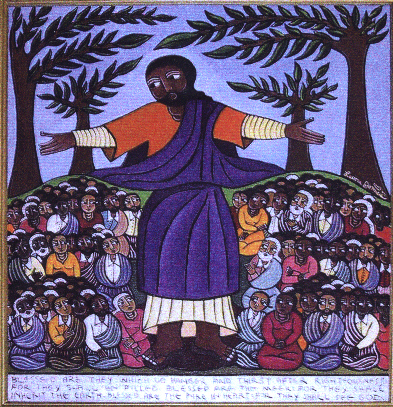

In Christ, Israel’s call to holiness comes to a strikingly paradoxical culmination. The difference, the distinction, the “set-apart-ness” of God’s people now reveals itself to be a unifying principle of all humanity– and indeed of all creation. The distinction between God’s Kingdom and the “world” is determinative for Christians, but at the same time it is also non-competitive: for the establishment of the Kingdom does not come at the expense of the world, but rather for the sake of the world. And so Christ teaches his disciples to distinguish themselves by their commitment to walk under the same sky with all who have been created in the divine image, the same sky through which the sun shines and the rain falls on the just and unjust alike. To “be perfect even as your heavenly Father is perfect” is to be an icon of God’s universal salvific love, to give this love a “face” through distinctive acts of love that go above and beyond the modes of reciprocity that characterize the wisdom of the world. For to regard each and every person as belonging to the people God desires as “His very own” is at the same time to inevitably set oneself apart from—and often place oneself at odds with—the fragmented and conflictive paradigms that rule this fallen world. To be holy in this world is to be weird; there can be no doubt about that. But the weirdness of true holiness is one that does not seek distinction and superiority, but rather solidarity and love.