I Kings 3:5, 7—12

Psalm 119

Romans 8:28—30

Matthew 13:44—52

This week’s lectionary readings nicely encapsulate the drama of human desire and the Christian understanding of how that desire might ultimately be fulfilled. St. Augustine once wrote that “all persons want to be happy; and no persons are happy who do not have what they want” (De beata vita 2.10). This way of putting the point expresses what in my view is the default human approach to desire and fulfillment: we find ourselves responding to the deep longings within us by reaching to the world in search of objects or experiences which might satisfy those longings. The dynamic is at work from our first breath, far before we are able to remember, express or deliberate upon these longings. Yet we desire not merely this or that form of satisfaction; we also desire something more, something global in scope: we seek out a stable and enduring state of contentment in which we can finally rest. In other words, we desire more than gratification; we want to be happy. And so begins the quest which characterizes so many of our lives—searching, waiting and working for what will bring our lives to their ultimate fulfillment.

Jesus himself clearly appeals to this dynamic in the Gospel passage for this Sunday, when he compares the kingdom of heaven variously to “a treasure buried in a field” and “a pearl of great price.” In both cases, the point being illustrated is that the kingdom of heaven is precisely that object of desire which exceeds and subordinates all others, that for the sake of which all others should be pursued. The kingdom of heaven is that singular discovery for which one would and should sell everything one has. Jesus sounds almost like a traveling salesman at this point: “come one, come all, behold the pearl of great price! It is worth more than you can possibly imagine! Bring me all you have, and I will sell it to you!” At the very least one must concede that Jesus is employing the notion of comparative worth here, appealing to the calculative dimension of our practical reason.

Yet immediately after these images, Jesus compares the kingdom of heaven to “a net thrown into the sea, which collects fish of every kind.” Some caught in its hold will be met with welcoming approval, while others will be thrown back. “Thus will it be at the end of the age. The angels will go out and separate the wicked from the righteous and throw them into the fiery furnace, where there will be wailing and grinding of teeth.” That’s quite a sharp turn in Jesus’ sales pitch, I’d say! The kingdom of heaven is a discovery of unsurpassable value, but it is also a force which gathers, differentiates and judges. So which is it? Is the kingdom a passive object of desire to be uncovered, or is it the vehicle of some pursuing agent?

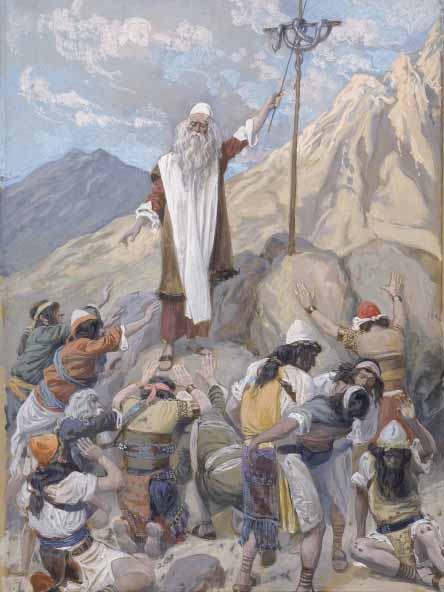

The answer, of course, is both; yet the order in which these two dimensions manifest themselves is of decisive importance. Here is where the first reading for today can shed some light. In this exchange we can see a kind of “holographic reflection” of the entire drama of Israel’s relationship with Yahweh, and indeed humanity’s relationship with its Creator. The most essential quality of this relationship is revealed at the very start: “the Lord appeared to Solomon….” Most of the time, lectionary readings such as these are impoverished by being lifted from their greater context, but in this case the delimitation is revealing. It is God who begins the encounter, who speaks first, who reaches out to reveal himself to a human being. And why? What is it that God wants to accomplish by doing so?

“God said, ‘Ask something of me and I will give it to you.’” The utterance expresses two elemental truths about God’s relationship to us. First, that God has no other motive in creating and interacting with us than irreducible generosity. God creates simply in order to give: to give existence to things outside himself, and ultimately to perfect that existence through the gift of himself. We are not given a clear reason in this passage for why God reaches out to Solomon with this offer, just as we are never given a reason why God has created and redeemed us. If all creation is ultimately pure gift, then it is a gift with no ultimate causal explanation other than love. Secondly, this offer to Solomon reveals that God is not satisfied with offering this unlimited gift; he also desires that the human person choose and request this gift for themselves. Here is where I might defer and simply say, “well, God, you know what’s best. Why don’t you decide?” But no, that’s not how it works. God not only desires to give us the best that can be given, but he wants us to freely request and accept it.

The drama of the scene is that God is offering to give to Solomon what all of us desire: the one thing we seek which we believe will not only gratify us but make us happy. Everything hangs in the balance! And needless to say, Solomon gets it right. But how?

The progression of human qualities reflected in his response is illuminating. First there is grateful acknowledgment of God’s sovereignty: “O Lord, my God, you have made me….” Then there is humble recognition of his own limitation and dependence: “but I am a mere youth, not knowing how to act.” There is also recognition that he is not “in this alone,” but that his fate and well-being is bound up with others, others to whom he is devoted and to whom he remains responsible: “I serve you in the midst of the people who you have chosen….” And then finally, there is the punchline, the request that cuts to the core of what we all most need and desire: “Give your servant, therefore, an understanding heart to judge your people and to distinguish right from wrong.”

Solomon seeks not just wisdom but an understanding heart. He does not ask for some cold, abstract knowledge which will allow him to transcend and escape the world of relationships and responsibilities in which he finds himself. Rather, he pleads for an ability to desire and love in a way that is guided by and ordered to that alone which can ultimately satisfy and perfect the human heart. Solomon asks for the sort of heart that can embrace and delight in the gift which God intends for him and for all those with whom his own life is intertwined.

We hear the song of this “understanding heart” in the Psalmist’s joyful ode to the Law. “The law of your mouth,” he sings, “is to me more precious than thousands of gold and silver pieces… For I love your command more than gold, however fine…. Wonderful are your decrees; therefore I observe them. The revelation of your words shed light, giving understanding to the simple.”

We too often conceive of wisdom as the ability to break away from convention and rule, but the Word of God offers us a portrait of wisdom that is much humbler, much simpler and much more profound: it is not we who find God, but God who finds us. It is not we who discover that “pearl of great price” which we all seek; it is freely given to us. It is not we who decipher a way of arriving at the end toward which our heart’s deepest longings direct us; it is the One who created that heart which calls and leads it down those well-trod paths that have been cleared for it to make its joyful journey home.