When we turn to Jesus as a foundation for doing ethics, we are presented with a significant challenge, a challenge that is really at the heart of Christian ethics. There is a clear tension between Jesus’ moral teachings and his eschatological worldview. The historical Jesus, one argument goes, had an imminent eschatology. He saw the world ending soon and the immediate fulfillment of the reign of God. Albert Schweitzer, the Protestant theologian known for his work on the historical Jesus, argued accordingly that Jesus provides only an “emergency ethic” for the interim between his life and the fulfillment of the kingdom, and as such is irrelevant for us today who live in the future that Jesus did not foresee–a future in which the end didn’t happen.

When we turn to Jesus as a foundation for doing ethics, we are presented with a significant challenge, a challenge that is really at the heart of Christian ethics. There is a clear tension between Jesus’ moral teachings and his eschatological worldview. The historical Jesus, one argument goes, had an imminent eschatology. He saw the world ending soon and the immediate fulfillment of the reign of God. Albert Schweitzer, the Protestant theologian known for his work on the historical Jesus, argued accordingly that Jesus provides only an “emergency ethic” for the interim between his life and the fulfillment of the kingdom, and as such is irrelevant for us today who live in the future that Jesus did not foresee–a future in which the end didn’t happen.

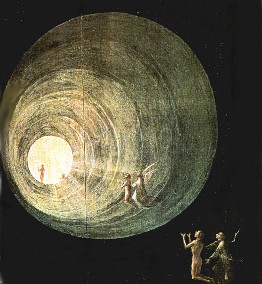

The Catholic counterpart to this view sees the most extreme of Jesus’ teachings, that is the teachings most rooted in his eschatological view that the world was ending soon, as counsels of perfection to be practiced by a chosen few (men and women in religious life, specifically). These counsels of perfection or evangelical counsels are contrasted with universally-binding precepts like the Decalogue that all people are called to follow. Those called to follow the evangelical counsels act as sort of prophetic witnesses reminding us of the coming end of the world, even as the world turns on. In this way, we hold on to both the eschatological urgency in Jesus’ teachings to not care for the things of this world but to seek the same perfection of the Father, but we also recognize the impossibility of putting such an ethic to work in a world where the fulfillment of the kingdom does not seem at all imminent.

On yet another extreme, we might say that the whole of Jesus’ moral teachings are universally-binding for those called to discipleship, and that even the most extreme (“do not resist an evil-doer,” e.g.) are moral precepts for every Christian to follow. This latter position we might call an ethics without eschatology, or, an ethic which requires followers of Christ to share his eschatology, even if it seems absurd to do so 2000 years after the failure of the kingdom to come. Although this position is often associated with pacifist Protestantism, some notable 20th century Catholics like Dorothy Day fit well into this view.

Now, this is a lectionary post which cannot even begin to do justice to the debate over Jesus’ ethics and eschatology but I wanted to mention it before we turn to readings which are eschatological in nature. “Be watchful! Be alert!” Jesus tells us in the Gospel. “You do not know when the time will come.” The fact is, most of us tend to downplay the normativity of Jesus’ ethical demands. We reason through various means that there are exceptions to the demand to not resist the evildoer, to give all that we have to the poor, to be like the lilies in the field that neither sow nor reap. I think this is because we don’t think that much about eschatology. Especially as Catholics who have a tradition (thankfully!) that doesn’t constantly search for scripture for predictions about the end of time, I think we have a tendency to ignore that the end of time will ever come at all.

I honestly like this about the Catholic tradition. There is a tension between realism and idealism. There are the demands of Jesus, but there are also the practical demands of the world, a world that cannot be ignored by a Church that wants to be too idealistic. Yes, Jesus says to not resist the evildoer, but innocent victims also need to be defended against aggression. Yes, Jesus says to give all to the poor and follow him, but my kids still need to eat and have a roof over their head.

During Advent, however, the lectionary calls us to put eschatology at the forefront for a while. We are called to reflect on the end and to restructure our lives and our ethics accordingly. This doesn’t mean that we embrace Jesus’ imminent ethic. After all, Jesus tells us in the Gospel that we don’t know the time. But it means that we begin to more consciously prepare for the end, to live a little more in such a way that the end really was coming. In this way, the liturgical cycle helps habituate us in the virtues necessary to be kingdom people, to, as Paul says in our second reading, keep “firm until the end.”