November 20, 2011 ~ Solemnity of Our Lord Jesus Christ the King

Ez 34:11-12, 15-17; Ps 23: 1-2, 2-3, 5-6; 1 Cor 15:20-26, 28; Mt 25:31-46

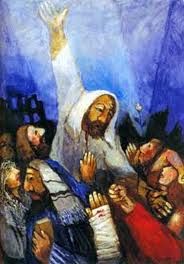

Established in 1925 by Pope Pius XI, the Feast of Christ the King was a response to the growing secularism of the day. It was a feast to remind men and women of the integral relevance of Christ, not only for their private lives but also for political life and public affairs. When the feast was later designated for the last Sunday of the liturgical year, there was some concern that the celebration of Christ’s kingship could be misunderstood. Indeed, it may appear that what we celebrate this Sunday is a triumphant victory lap for the greatest of all sovereigns. However, the point is that to call Christ “king” is to upend our creaturely notions of power, authority, and empire.

The scriptural motifs of reversal and surprise emerge easily from this week’s readings. In the first reading, Ezekial gives us the image of God as shepherd, hardly the profession of royalty. Yet, as readers of Scripture, we cannot help but find it fitting. Indeed, after inspecting all of Jesse’s apparently eligible sons, Samuel anointed David who had been out tending the sheep (1 Samuel 16:1-13). God as shepherd rules with a profound personal care for each one, especially the suffering and forsaken: “I myself will pasture my sheep; I myself will give them rest, says the Lord GOD. The lost I will seek out, the strayed I will bring back…” (Ez 34:11-12)

In the Gospel reading from Matthew, the surprise is to discover that it was Christ who was hungry, thirsty, naked, and in prison when the least of our brothers and sisters were being served. The one who “will sit upon his glorious throne” (Mt 25:31), is at the same time the one who is present to the overlooked and unremarkable. All are surprised (both those who show mercy and those who do not) when the Lord reveals this unseemly solidarity with the outcast and marginalized. And yet, what should we have expected from the one who took up our fleshy humanity?

Despite apparently sufficient opportunities to comprehend that God and God’s reign defy the human model of kingship, we continue to be dumbstruck. Perhaps we need to keep ushering in these reminders of the radical departure our God makes from the creaturely patterns of power and authority. Toward this end, I recommend a verse from the second reading: “The last enemy to be destroyed is death.” (1 Cor: 15:26)

At first glance, this seems to be an unexceptional gesture toward the juxtaposition of life and death that we hear at the beginning of the second reading: “For just as in Adam all die, so too in Christ shall all be brought to life” (1 Cor 15:22). Yet, the identification of death as enemy follows on a proclamation of the kingdom and gives us reason to pause at the radical newness of that kingdom. For what sort of empire has ever had death as an enemy? Without mortal fear, can there be any true coercion, any force, any leverage? Death is what makes earthly authority possible. Death is a friend, a tool, of human kingdoms. It is why we preserve them with war and strengthen them through torture. Death persuades us to willing submission and the conspiracy of silence. This death is the enemy of the kingship of Christ and a scandal to God’s reign.

This Sunday we are welcomed into a surprising vision of the tender sovereignty of our God where the most insignificant and undesirable are transformed into the precious and indispensable. It is a vision that ought not merely animate our prayers and eschatological hopes but should daily shape our participation in this world and the powers and authorities that have become friends of death.

In establishing the feast of Christ the King, Pope Pius XI entreated the faithful to “look for the peace of Christ in the Kingdom of Christ.” God’s reign is not of this world but it is for this world. We are called not only to “look” for that peace but to cultivate it, especially in the midst of human authority and empire.