Psalm 93:1-2, 5

Revelation 1:5-8

John 18:33b-37

This Sunday we celebrate the Solemnity of Christ the King, a feast which not only commemorates the ultimate sovereignty of our Lord, God and Savior Jesus Christ but also marks the last Sunday in the liturgical year. It surprises most contemporary Catholics when they learn that this feast is a relatively new addition to the Church calendar, having been instituted less than a century ago by Pope Pius XI alongside the publication of his 1925 encyclical Quas Primas (QP). The feast should especially interest moral theologians in so far as its institution emerges out of what we would classify today as a “social encyclical,” which gives the commemoration a political edge that has clearly been lost over the course of the past eighty years.

The feast of Christ the King was originally designated for the last Sunday in October, the one immediately preceding the feast of All Saints. Pope Pius XI is very clear and explicit about the desired effects he hoped the feast would have with regard to the Church’s relation to the broader society. First, he hoped the feast would emphasize the Church’s proper immunity from State interference (QP 32). He also expressed the hope that nations and their leaders would come to pay due respect to the sovereignty of Christ in the exercise of civil authority (QP 31). And finally, the feast was meant to admonish the faithful to honor Christ as King in their own hearts, minds, souls and bodies (QP 33).

In perfect accord with the overall trajectory of Pius XI’s social thought, the feast of Christ the King was a response to the mounting nationalism and emerging secularism which increasingly characterized the state of European society after the Great War. The story is a long one, and better relayed in other genres and venues, but suffice it to say that this period in history marks the full completion of the centuries-long journey from the Church to the nation-state as the wellspring and epicenter of cultural identity in the West. It is a rather safe claim to make that by 1925, Christ’s kingship is no longer a visible and vital aspect of political life in Europe and America. And so with this feast we see Pope Pius XI reaffirming in the face of the triumph of Enlightenment polities the unwavering claim of Christ’s kingship over all mankind and all creation.

In fact, I think it true to say that most Americans look at this feast either with bewilderment or antipathy. We may feel merely bewildered if we remain under the understandable impression that this feast (like so many others) dates back many centuries to the time when kingship was a omnipresent and potent aspect of political life. Yet once we learn that the feast was instituted well after we declared our own national independence from a king, that bewilderment may very well turn to antipathy. After all, our country was founded upon an explicit act of rebellion against a tyrannical king, and in many ways against the very idea of kingship itself. Even if unlike their French counterparts waiting in the wings, our founding fathers did not identify political kingship with religious authority tout court, it remains true to say that they explicitly rejected any political and social order in which kings were a natural part.

We may not prefer (as did Diderot) to kill our kings with the entrails of priests, but we would still like to see them dead nonetheless. Thus the task of envisioning Christ as “king” is something especially challenging for the American imagination. Yet the quality of this kingship as reflected in the Gospel reading for today is something so utterly different from what we think of when we think of kingship (or any form of political authority for that matter) that we would do well to dwell upon this scene and to allow the notion of sovereignty itself to become strange to us once more.

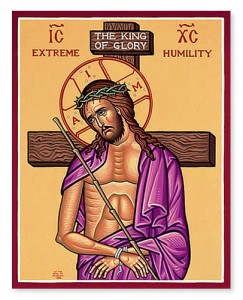

The picture presented to us in this scene from the Gospel of John is one that is widely depicted in Byzantine iconography and specifically related to another title of Christ, namely that of “the Bridegroom.” The icon of Christ the Bridegroom, often displayed during the Holy Friday liturgies, shows Christ robed in red, with his reed scepter in his hand and His crown of thorns upon his head, and often standing within the walls of a stone box representing his waiting sepulcher. The words often inscribed on this icon are simple and to the point: “Extreme Humility.” This icon, like the Gospel account itself, leaves little work for us to connect this moment in Christ’s passion with his claim to ultimate kingship. Here is the moment when the king stands before us in his glory and sovereignty, and it is the same moment when he also appears to us as “the Bridegroom.”

The soldiers place a crown of thorns upon Jesus’ head as an act of mockery and humiliation. Yet it is the only crown which Jesus wears. It is his crown. What a silly and almost blasphemous notion that Jesus, upon ascending into heaven, would exchange this crown for a more “suitable” and sparkly crown of gold and precious jewels. No, if it was fitting that Christ rise with his scars intact, then it is all the more fitting that he wear his crown of thorns as the sign of his eternal kingship. For just as the marks in his hands and side signify not infirmity but love, so also the thorns upon his brow are a mark of his triumph over our sins.

I forget exactly where I came across this idea (perhaps in Julian of Norwich? perhaps in the hymnody?), but I have always been drawn to the image of Jesus crowned with a crown made up of my own sins, which pierce his sacred flesh. The deepest meaning of this image is not that it awakens in me a sense of genuine sorrow for my sins (although it does), but rather that on Jesus’ head those sins become marks of triumph: trophies that commemorate his victory and his sovereignty over our every effort to scorn and mock his love.

This scene before Pontius Pilate bears repeated contemplation. The reign of Caesar has instilled in Pilate, and maybe even relies upon, a sense of the malleability of truth to fit the whims of human desire. Pilate is awed only by Jesus’ own lack of awe before him, and seems concerned primarily with reasserting his power over life or death. “Don’t you realize what I could do to you,” he asks Jesus. “You have no power that does not come from above,” is Jesus’ reply. The irony is obvious, yet profound: the provincial ruler (for that is all any human being can amount to in the end) stands before the King of all, the Bridegroom, crowned with his crown of triumphant love, and wielding his scepter which will smash the gates of hell. What is truth, indeed! What is the true reality of what is going on here? Who is the real judge, and who is the one being judged?

So it is with Pilate, and so it is with every earthly ruler. In their dealings with the last and least among us—the most vulnerable, the ones most susceptible to humiliation and injustice—the provincial authorities in our midst stand before the King and Bridegroom himself. And as with Pilate, this King judges them by their own acts of judgment.

As we commemorate the kingship of Christ, let us remember above all the kind of king we serve: a king “who does not deem equality with God something to be grasped, but who rather emptied himself by taking on the form of a servant.” For this king, sovereignty is ultimately indistinguishable from suffering. For this king, “to serve is to reign.”

Today He who hung the earth upon the waters is hung on the tree,

The King of the angels is decked with a crown of thorns.

He who wraps the heavens in clouds is wrapped in the purple of mockery.

He who freed Adam in the Jordan is slapped on the face.

The Bridegroom of the Church is affixed to the Cross with nails.

The Son of the virgin is pierced by a spear.

We worship Thy passion, O Christ.

We worship Thy passion, O Christ.

We worship Thy passion, O Christ.

Show us also Thy glorious resurrection.

—Fifteenth Antiphon for Great and Holy Friday

Trackbacks/Pingbacks