Two apparently unrelated things have been on my mind this week. One, of course, is the resignation of Pope Benedict XVI and the subsequent media war we’ve all come to expect. Taking a look at the comboxes and FB feeds this week, it seems that many take this as an opportunity to remind us of Pope Benedict’s sins (real or presumed), and even to wonder if this isn’t a conspiracy, that somehow Pope Benedict’s resignation is actually a signal of some secret and more heinous crime that he will commit in the future (!). Many won’t miss him at all, seeing him as yet another archaic representative of a hierarchy that needs to disband. The pope’s resignation is a harbinger of dawn, a possibility of change, since resignation itself changes the focus of the papal office. Others have taken the “other side” – they WILL miss him and they especially will miss the kind of security that a pope-until-death brings to the office.

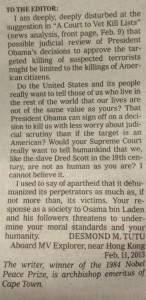

The other “thing” is the photo that has been shared numerous times on Facebook as well as over at NPR, of Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s letter to the editor in the New York Times (shared by Sree Sreenivasan).

The archbishop expresses astonishment that we Americans would even think of limiting judicial review of possible drone strikes to killings of presumed American terrorists (but that other presumed terrorists wouldn’t/couldn’t get the same kind of judicial review).

“Do the United States and its people really want to tell the rest of the world that our lives are not the same value as yours?” he asks.

America appears on one side, while the rest of the world appears on the other side. The loophole allows us to pretend that we have humility about our own sense of rightness. That the President might be wrong about a suspected American terrorist doesn’t appear to carry over to the possibility of being wrong about suspected other terrorists. It makes us two-faced: we appear to care about second chances, loopholes and the ability to change for ourselves, but obviously every one else (especially those who disagree with me) can’t possibly receive those same chances, because they’re going kill and maim me (so the presumption seems to go, whether you’re the pope or a suspected non-American terrorist).

Two apparently disparate things – but both highlight our need for a false sense of security, especially a sense of security in our own rightness (or need to be right).

To vilify a pope so much that the world suddenly seems righted when he resigns – or to love a pope so much that the world suddenly seems scary when he resigns – is to put too much stake in the world as we see it, and especially in our own views of what is right and wrong with the world. Ditto for loving Americans so much that “the other” who is not American can be conveniently killed on the slightest suspicion of terrorism, not receiving the same benefit of the doubt that we’d give to one of our own.

The Lenten season of repentance focuses especially on humility – and the important lesson of humility is that it especially frees us to see ourselves as not having the whole picture of things. It also therefore frees us to see others as nuanced – to see, for example, that the Pope is both someone who misspoke (with very bad effect) at Regensberg, thus hindering Christian-Muslim relations, but also someone who has done amazing work toward environmental causes. It enables us to see non-Americans as people worthy of the same chances we have, even though they may appear scarily terroristic.

The interlocutor I most often use in my academic writing is Saint Augustine of Hippo, who famously wrote about The Two Cities – the Earthly City and the Heavenly City. But these weren’t two separate, dichotomous places – these were bound up together and you didn’t know the one from the other. Augustine uses other images to discuss this intermixing – fishes caught up together in a net, good and bad together; the Gospel image of the sheep and the goats (who won’t be separated until the end of time).

I think Augustine’s exactly right here. That’s not only because good and evil are intermixed in our world – but also because part of seeing ourselves rightly is being able to see our own intermixedness. If we are to recognize another’s ability to be both sheep and goat, it begins by recognizing that our own humanity, too, is both sheep and goat.

We can’t get away from that, this side of heaven. But what we can do is recognize that fact of ourselves – and in recognizing that, recognize that we are prone to perpetuating an evil (that of assuming the worst of others and their viewpoints, and the very best of our own) that we don’t want to see.

To recognize this point is to simultaneously realize that the whole world, ourselves included, is in need of great love and forgiveness. And isn’t that, really, the message we want to give?