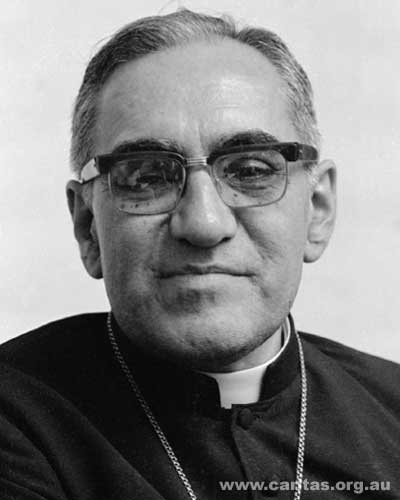

On February 3, Pope Francis claimed Archbishop Oscar Romero a martyr. Oscar Romero was killed while saying mass on March 24, 1980. It has been 35 years since his death and 22 years since the Vatican opened his cause for sainthood. Why is he only now being declared a martyr? The Catholic News Service reported that the delay was because . . .

. . . the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith studied his writings, amid wider debate over whether he had been killed for his faith or for taking political positions against Salvadoran government and against the death squads that were operating in his country. As head of the San Salvadoran Archdiocese from 1977 until his death, his preaching grew increasingly strident in defense of the country’s poor and oppressed.

Most of us who have taught moral theology have, at one time or another, drawn on the example of Archbishop Oscar Romero. His words and witness provide an excellent example of the fundamental assumption in moral theology: if one believes in the gospel, one’s actions in the world should reflect it. Most of moral theology is figuring out how to do this in different cultures and in the face of different challenges.

The hesitation over declaring him a martyr seems strange. Shouldn’t one’s faith lead to being against death squads? If one is not against death squads, isn’t there something wrong with one’s faith? How can one separate the actions that flow from faith from the faith itself?

To be sure, we should heed C. S. Lewis’ call for “mere Christianity”. The gospel should never become an instrumental philosophy to support some cause, whether it is political or economic, personal or professional. It is to God we owe our ultimate love. Yet, it is this love—which is a response to the love God first showed us—that transforms our ways and days. It is Jesus who taught that by our fruits, our love of others, and our treatment of the least of our brothers and sisters that we are known and judged.

This clearly seems the case with Romero. It was his commitment to the incarnation that drove him to care for people’s physical and spiritual needs. He was not seeking political power but an end to a way of acting that stood in opposition to God’s ways. He pursued a world were power and violence did not rule but love did. It is why in his last homily, Romero said,

I would like to make a special appeal to the men of the army, and specifically to the ranks of the National Guard, the police and the military. Brothers, you come from our own people. You are killing your own brother peasants when any human order to kill must be subordinate to the law of God which says, “Thou shalt not kill.” No soldier is obliged to obey an order contrary to the law of God.

The delay in decreeing Archbishop Romero a martyr should not delay us from imitating him. Let us try to practice our faith more consistently in our lives and repent more quickly when we don’t. Let us embody a politics that is not focused on gaining power but one that strives to make our communities more consistent with the law of God. Let us make it easier to live and harder to kill.

It is no easy task. We are to manifest God’s love in our living and in our dying. Our savior said this. Our savior lived this. And the martyrdom of Romero reflects it.