A recent letter to the editor in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette criticized the recent protests among fast-food workers about minimum wage. The author tells how she started out at a fast-food job and then, realizing it did not pay enough, went to community college part time, paid for it herself, got a better job, earned a bachelors degree, got an even better job, and now, while not rich, makes a decent living. Why, she asks, don’t these people work hard to improve their situation instead of just being lazy and complaining about it?

I hear this complaint often in Appalachia. It does not come from the wealthy in the community, though. It comes from the middle to lower class. It comes out of the culture I grew up in and where I now reside. It comes out of a place where poverty is rampant. While the nation’s unemployment rate dipped to 7%, this area’s unemployment is still almost 8%. The complaint comes out of a history of almost a hundred years of exploitation, first by the timber industry and then the coal mining industry. It comes out of a region that is poor but should not be. It is racially and religiously diverse, with a rich heritage of music and story telling. It values hard work and self-sufficiency, about care for family and faith in the Bible.

I have come to think that the Appalachian complaint about the poor being “lazy” isn’t actually about this at all. Why in an impoverished area would they complain about the poor? If they are not poor themselves, any Appalachian knows someone who was or is poor. My students voice this concern about laziness even when so many of their parents worked for minimum wage and experienced periods of unemployment or drop in income. Moreover, one finds great sympathy for the poor in this area. The efforts of these communities to feed the poor are just one outstanding example.

I also don’t think this complaint about laziness is a dismissal of the social structures that give rise to and trap people in poverty. People in this area know well that there are factors beyond their control that effect their ability to earn a decent wage and make a decent living, no matter how hard they work. Whether it was the timber industry in the late 1800’s or coal mining in the early 1900’s or the natural gas industry now, residents know that there are large corporation who control the work force in the area and care little or nothing about the workers. As the classic song, “Sixteen Tons”, goes,

You load sixteen tons, what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt!

Saint Peter don’t you call me ’cause I can’t go,

I owe my soul to the company store.

Finally, I don’t think the complaint is advocating a path to wealth, a “if you work hard, you will get rich” platitude. Wealth and the rich are perhaps more scorned than the “lazy” poor. Those in the upper class in this area are typically thought of as the ones (or descendants of the ones) who exploited laborers and now live a spoiled life off of these spoils. Moreover, the typical Appalachian does not desire a lot of money, make a lot of money, climb the corporate latter, or pursue success at the cost of faith or family. Appalachians are not interested in that kind of wealth.

I think the criticism is ultimately about human dignity. Stripped of economic success, in an environment where business is more powerful than you and politicians protect business and not you, how do you hold on to your dignity? You do it through character, by working hard and doing what is right, even if you are not rewarded for it.

It is why the complaint about the “lazy” poor is always accompanied by a story of how that person or that person’s relative was poor and, yet, kept working and kept going. This seems to be the point of the story. It poses a choice: are you after rewards? Or do you do what is right? In Appalachia, there are no rewards, so the only real answer, the only answer that preserves your dignity, is “hard” work.

It is why one of the verses of “Sixteen Tons” goes,

I was born one mornin’ when the sun didn’t shine

I picked up my shovel and I walked to the mine

I loaded sixteen tons of number nine coal

And the straw boss said “Well, a-bless my soul”

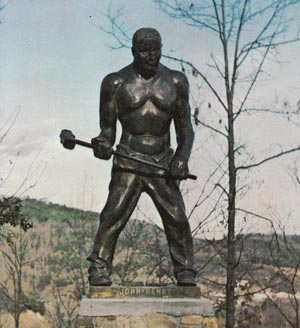

It is why the most famous legend from Appalachia is John Henry. It is the story of how John Henry raced a steam engine hammer to dig a tunnel. He won but died after his victory. The victory does not bring financial reward but rather proof of the value of the human spirit, a value that ultimately wins out over machines as well as the rich who have no respect for working or workers. In one variation of this tale, right after John Henry dies, his wife picks up his hammers and keeps on going. This ending, it seems, is the Appalachian spirit: the dignity of the person cannot be stopped, no matter the adversity.

It is why, I think, the people of Appalachia tend to have a strong faith in the messiah that did God’s will, even though it lead him to his death.

As a life long Appalachian myself I am not as optimistic about the deeper meaning of the laziness complaint. When I hear this kind of thing (which is very often) I take it to be more of a ‘crabs in a bucket’ situation. Poverty and lack of opportunity creates a kind of spitefulness and a need to define oneself as better than one’s very similar neighbors as if it’s a zero sum game. And when your neighbor strives for some kind of betterment keep your superiority by pulling him back down or explaining his achievement away. If fast food workers achieve a raise it will be through a ton of hard work and bravery, but but for those who make just a couple dollars more in slightly more prestigious working class jobs that explanation won’t do. It will be because they were lazy and greedy and the government and bleeding heart liberals and foolish city people gave them an unfair advantage.

Jason,

Thank you for this post. I want to make a couple of points beginning with a Song recommendation — have you heard Christy Moore’s Ordinary Man? He is an irish folk singer and the song (written by someone else during Thatcher years) is quite powerful…a key line “I’ll never forget how you stripped me of my dignity and pride.” The song is about closing factories, rising unemployment coupled with rising inequality under Thatcher.

I found your post very helpful – because I agree the invocation of the “lazy poor” is more complicated problem to address. I want to propose 2 things to consider that aren’t addressed in your post. First, I think Karol Woytla’s writings on participation and alienation – which look at protests could add to the complexity here. Often part of the problem is the inability to reject or claim the system must change — “following the rules” means accepting the rules as framework. Sometimes that cannot happen – the rules are unjust. But this has always been controversial for many – enter LETTER FROM A BIRMINGHAM JAIL.

Second, I think the problem of “deep faith” must be examined for issues relating to “deserving/undeserving poor” (understood through a particular vision of “hard work” and “following the rules” coupled with not getting “ahead of yourself”) along with problematic views of suffering and the cross which work against impetus for protest, social movements and change. Doing God’s will meant the cross…but it did not mean capitulating to unjust structures — this is where WHY the cross vs. simply accepting it is important.

Anyway, so glad you posted this and just some points to think about – and look up the song, its beautiful.