“God sent his Son, born of a woman…” (Gal 4:4-7)

“Mary kept all these things, reflecting on them in her heart.” (Lk 2: 16-21)

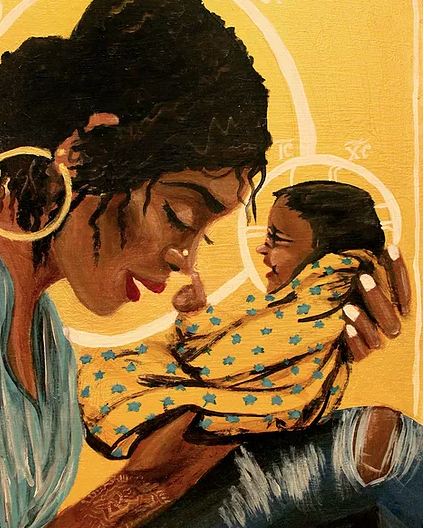

The Solemnity of Mary, the Mother of God, is an opportunity to contemplate the person of Mary. Very little is written of her in our Scriptures. She was a first century Jewish woman with deep faith who co-parented Jesus of Nazareth, whom Christians profess is the Christ, God Incarnate. Thus among her many titles are Theotokos and Mater Dei, “God-Bearer” and “Mother of God.” Many historians will emphasize that the Council of Ephesus in 431, in approving the title Theotokos, was making a Christological claim (in other words, that Mary’s title is really about Jesus). To claim that Mary is the Mother of God means that Jesus really is God. But today’s feast invites us to contemplate the reality of God’s incarnation through female consent, agency, and embodiment. Devotions that honor Mary are often a mixture of popular piety, storytelling influenced by exaggeration and ego, and attempts to lure travelers to destinations where the Virgin appeared or miracles occurred (yes, pilgrimages were sacred journeys that stimulated local economies). Many Marian devotions, embedded as they are in particular historical and geographical contexts, carry with them implicit claims about gender, power, and the natural law. It can be confusing to sort through them, especially if we aim to seek out an image of Mary that is liberating for contemporary people. My students often puzzle over the mystical visions of saints who nurse at the breast of the Mother of God; artistic representations of St. Anne pointing to the genitals of the baby Jesus; the story of St. Catherine of Siena receiving the holy foreskin of the infant Jesus to wear as a wedding ring; and hymns praising Mary as a military champion and defender of the imperial state.[1] I join them, wondering what it all means. What does it mean to be a good mother? What does holiness require? What virtues should I prioritize in my devotions, and what spiritual resources would be the best guide for me?

I find that there are often not easy answers to these questions for me today. And as I have developed a stronger sense of my own dignity as a woman, and the importance of female voices in shaping theology, I’m often overcome with sadness and frustration that Mary’s story has been told by men, and that our liturgical experiences continue to be so male-dominated in Catholicism. For example, when I remember the terror of childbirth and my recovery afterwards, reading Bernard of Clairvaux’s insistence that Mary had gone through childbirth effortlessly, like a star radiating light, with her virginal purity intact, hardly brings comfort. It seems to me that we need more women to tell the story of Mary—women speaking from their pain and grief, joy and love, hopes and sorrows. Two books I highly recommend are Ivone Gebara and Maria Clara Bingemer’s Mary: Mother of God, Mother of the Poor and Elizabeth A. Johnson’s Truly Our Sister: A Theology of Mary in the Communion of Saints.

If I were to name some of the basic reasons why today’s feast is important, I would highlight these two:

(1) Women’s bodies are sacred.

Woman have inherent human dignity and are worthy of respect. All women: Virgins, mothers, single, married and widowed women, lesbians, women in irregular partnerships, women of all ages and social locations. All women should be treated with respect. When Catholics celebrate today, we celebrate how Jesus was “born of woman.” We celebrate the sacred power that women of childbearing age have. But today is also a day to mourn, for we have lost our way. Every day in 2017, according to the WHO, approximately 810 women died from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth. Our tradition speaks of Mary’s consent to bear the Christ child. But sexual violence is pervasive in US culture today. More than 1 in 3 women have experienced sexual violence that includes physical contact. When men are groomed to feel a sense of entitlement to women’s bodies, this creates toxic relationships. Christine Firer Hinze and Sandra Sullivan Dunbar have argued that care work makes possible all other economic activity, and yet we consistently undervalue the people who care for vulnerable others in our economy, workers who are disproportionately women of color. The wage gap is real: women who work full time in the US are paid 82 cents for every dollar paid to men, and for women of color the wage gap is even larger. Today’s feast is an opportunity to remember Mary’s labor: not just the labor of pregnancy and childbirth, but the labor of parenting him through the toddler, teenage, and adult years; the labor of sustaining community in the wake of his death; her leadership and ministry that was so often underrepresented and undervalued in her day. Pope Francis writes in Fratelli Tutti that “the organization of societies worldwide is still far from reflecting clearly that women possess the same dignity and identical rights as men. We say one thing with words, but our decisions and reality tell another story” (23). Today’s feast invites me to recommit to creating laws and structures that fully honor the dignity of all women.

(2) Mary is sister to the marginalized

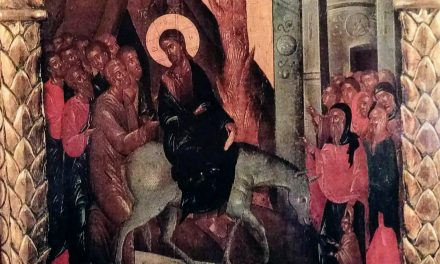

In today’s gospel, Luke’s narrative describes Mary and Joseph caring for the Christ child in a humble dwelling of a manger, for there was no room in the inn. Lowly shepherds learn of the good news. Nativity scenes in our sacred spaces today can remind us of the humility of the Christmas miracle, but the danger of the scene is often not captured in those pious creations. Ivone Gebara, Maria Clara Bingemer, and Elizabeth Johnson retell the story of Miriam of Nazareth in such a way that they highlight the particular relevance of her life for people on the margins today. Johnson writes:

“Giving birth in a homeless situation; fleeing as a refugee with your baby to a strange land to escape being killed by military action; losing a child to unjust execution by the state—our newspapers yield up these icons of suffering even today. Mary is sister to the marginalized women who live unchronicled lives in oppressive situations. It does her no honor to rip her out of her conflictual, dangerous historical circumstances and transmute her into an icon of a peaceful, middle-class life robed in royal blue.”

E. Johnson, June 17-24, 2000. America. page 13.

Today’s feast invites me to ask: How am I sister to the marginalized today? How can Mary’s faith in a God who exalts the lowly and fills the hungry with good things become my own?

In a time of pandemic liturgies, devotional practices at home can provide new opportunities for stretching one’s spiritual imagination. Walking meditations, the rosary, breathing meditations in front of lit candles, lectio divina, examen, singing, and many other forms of prayer can fill our solitude with mindful attention to the work of the Spirit in our daily lives. The National Black Catholic Congress resource page on Marian devotions may be helpful for those seeking new ways of praying today.

Mary, Mother of God, Sister

to the Marginalized, Undoer of Knots, Pray for Us.

[1] See David Chidester, “Mary,” in Christianity: A Global History (New York: Harper One, 2000): 275-292; Bradley P. Nystrom and David P. Nystrom, “Controversies, Councils, and Creeds” in The History of Christianity (New York: McGraw Hill, 2004): 88-96; Elizabeth Johnson, “Mary of Nazareth: Friend of God and Prophet,” America 182:21 (June 2000): 7-13.