Lectionary 34

Ezra 37:12—14 / Psalm 130 / Romans 8:8—11 / John 11:1-45

A colleague of mine once received a student’s paper on the theme of resurrection which began: “I am aware of two chief instances of resurrection: that of Jesus Christ, and that of zombies. Since zombies are not mentioned in the Bible, this paper will deal solely with the resurrection of Jesus Christ.” It was funny, but it was also woefully underinformed. The student clearly did not remember the three accounts in the gospels where Jesus raises an individual from the dead: the raising of Jairus’ daughter in Matthew 9, the raising of the widow’s son in Luke 7, and the raising of Lazarus in John 11, the latter of which serves as the gospel reading for this Sunday. Before we look into the Lazarus story in particular, we should pause to consider these dramatic acts within the context of Jesus’ public ministry, as they were experienced prior to his own resurrection. Knowing the end of the story, it is all too easy for us to read them as foreshadowing, as if Jesus is accomplishing for these people here and now some measure of what he will eventually accomplish for all the world: the destruction of the “final enemy”—death itself (I Cor 15:26). No doubt that is what he is doing, but that way of seeing things lies well in the future. How might the people of that time and place have understood the meaning of these miracles? Happily, John gives us much to work with in pondering this question.

The first detail is that a certain man was ill. It’s easy to pass over, but it’s of enormous significance. That there is illness in the world or that many people are ill at this very moment is not a truth we usually spend much time thinking about, because it is so abstract and so obviously true. It is only when those we know and love become ill that the real meaning of this fact begins to come into focus. “People have cancer” is an extremely blunt and prosaic statement; yet “Mom has cancer” or “my daughter has cancer” are among some of the most penetrating and world-transforming words one can hear. That is why it matters that Jesus knew the man who was ill: it was his friend, Lazarus of Bethany, the brother of Mary and Martha. John here mentions that “Mary was the one who had anointed the Lord with perfumed oil and dried his feet with her hair” (Lk 7:36-50). She was the one who was forgiven because “she loved much.” More specifically, she loved Jesus much, as did her brother. The sisters send for Jesus with the simple message: “Master, the one you love is ill.” St. Thomas Aquinas makes this beautiful remark on this verse in his Commentary on John:

his sisters do not say, ‘Lord, come and heal him,’ but simply mention his sickness, that he is ill. This indicates that it is enough merely to state one’s need to a friend, without adding a request. For a friend, since he wills the good of his friend as his own good, is just as interested in warding off harm from his friends as he is in warding it off from himself. And this is especially true of the one who most truly loves: ‘The Lord preserves all who love him’ (Ps 145:20).

Aquinas also makes the observation this incident definitively puts to rest the dispute in Job over whether God ever permits his faithful to undergo affliction. Because Lazarus truly loves the Lord, he is truly his friend. His illness is therefore proof that Eliphaz was wrong: “if someone has a bodily illness, this is not a sign that the person is not a friend of God.”

What is more, the gospel passage makes clear that Jesus sets out to Judea in the face of danger. His companions point out to Him that He was recently the target of stoning by those living in Judea. Yet He sets out nonetheless for the sake of His friend, because He loves him. And so Thomas remarks, perhaps wryly: “let us go, that we may die with him.” Wryly or not, Thomas is willing to go even at the risk of his own life to honor the love of his Master’s friend. Such is the bond of true friendship.

Why should Jesus bother, though, if Lazarus is already dead? If he’s dead, then isn’t it God’s will that he remain so? As in John 9, when Jesus rebuked his disciple’s question as to whose sin caused a man’s blindness, the easy explanation of illness and death falls out at once in this narrative. John places all his favorite images of the Lord’s presence in the world—life, light, love, logic—directly alongside all their opposites—death, darkness, oblivion, chaos—so as to affirm the vital truth that the two sets need not be imagined as simple contraries in a strictly proportional relation, such that could be taken as the cause of the other. As the Light of Life himself reached out to touch the man’s eyes and overcome his blindness, so He now reaches into the tomb to bring Lazarus back from the realm of death and corruption.

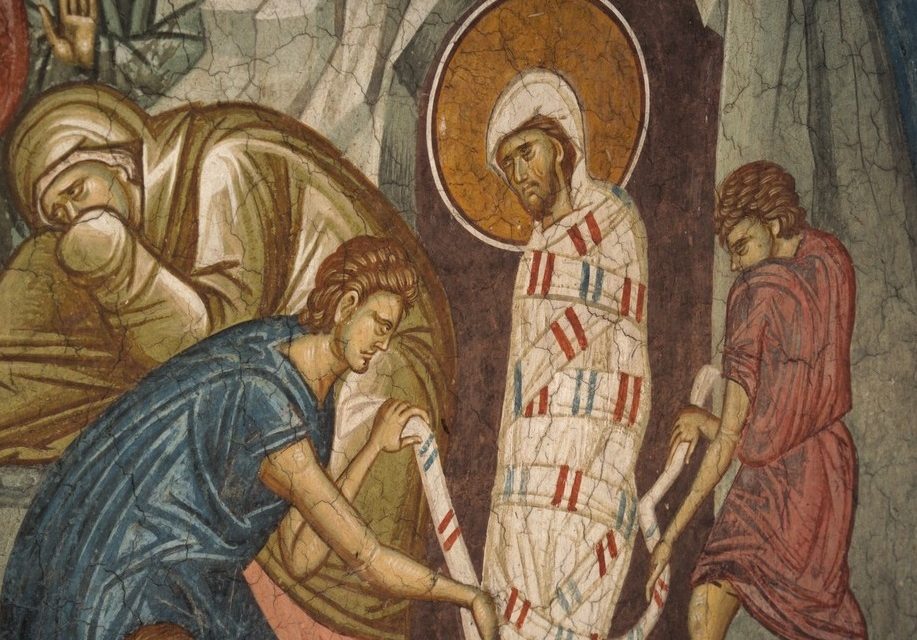

But why exactly would Jesus do it? Why would he bother to revivify a corpse that had already begun to decay? Hadn’t the time for dramatic action passed? Jairus’ daughter and the widow’s son were only very newly dead. Lazarus had been in the tomb four days, and as his onlookers pointed out, there would likely be a stench by now. It was Jesus’ own decision to delay, and Mary was apparently not happy about it: “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died,” she said. “But even now I know that whatever you ask of God, God will give you.” To which Jesus simply responds, “Your brother will rise.”

We do not know how Mary might have been feeling about this assurance, but we do know that she understood it eschatologically. “I know he will rise at the resurrection on the last day,” she says. Might she have felt as so many of us have when people remark how our dead loved one “is in a better place” or “don’t worry; you will see her/him again one day?” So often this type of abstracted consolation serves a way to avoid the possibility of entering into another’s grief. To it Jesus emphatically answers in the present tense: “I am the resurrection.” The incarnate Lord is not interested in pie-in-the-sky platitudes because He embodies in Himself, at that very moment, the fullness of all the promises of God, including the promise given in Ezra (our first reading) to “open your graves and raise you up from them, and bring you back to the land of Israel” (Ez 37:12).

Jesus enters this scene in order to give life to his friend, and to restore him once more to those who were grieving his absence. He could have done it from far away, as soon as he received the message from Bethany. He could have done it right away, as soon as he arrived there. Yet he waits, so as to speak with those who are there and enter fully into their experience of death. For the real bitterness of death is always one’s experience of the death of another, both because those we love are now gone and also because we see clearly at such moments where our own life-stories will end. And Jesus does not shy away from this experience. He allows himself to be “troubled,” “perturbed” by it. And he weeps. He feels it; he enters into it fully.

Jesus then prays to the Father, and gives life to the dead by commanding Lazarus to “come out.” The Father and the Son are there, but where is the Spirit? It is easy to overlook the role of the Spirit in this story, but the other lectionary readings will not let us, which is good because in a sense the Spirit is the key to understanding the meaning of the whole event. In the first reading the Lord declares through the prophet Ezra: “I will put my spirit in you that you may live, and I will settle you upon your land; thus you shall know that I am the Lord.” In the second reading, St. Paul explains that we can please God only if we are “in the spirit,” meaning only if the Spirit of God dwells in us. Paul then concludes that “if the Spirit of the one who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, the one who raised Christ from the dead will give life to your mortal bodies also, through his Spirit dwelling in you.” The key to life beyond the grave therefore has nothing to do with the qualities of our flesh, but is rather a matter of what spirit is in us. For if the Spirit of Christ is in us, then Christ himself is in us, and so we can partake in the resurrection that He alone can accomplish.

Because in the end, you see, the enemy was never really death, but rather the meaninglessness and isolation of our own existence without God, the eternal Good. Death remains the purest and clearest expression of this futility, of this contradiction within ourselves, and so we fear it, and let it rule us. But the good news is that Jesus Christ reaches directly into this futility with his own hand and contradicts this contradiction with his own mouth. “Come out!” he says. Appearing to us in a body like ours, He offers us His own flesh and blood that we might bear His Spirit within us and so be raised up like Lazarus on the Last Day. He submits himself to death “so that through death,” as the Apostle says, “he might destroy the one who has the power of death, that is, the devil, and free those who all their lives were held in slavery by the fear of death” (Heb 2:14-15). It is from this bondage above all that Jesus liberates us. And so what emerges from the burial cloths as they are removed from Lazarus is not merely a functioning human organism, but an entirely new creation: one no longer fatally bound by the fear of death, but rather a friend of God bearing within himself the very spirit of Christ, who possesses a hope full of immortality that can never be destroyed.