In his address to the U.S. Congress in September, 2015, Pope Francis pointed to four great Americans who “shaped fundamental values which will endure forever in the spirit of the American people”: Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Jr., Dorothy Day, and Thomas Merton. Although for Americans it was not surprising that King would be identified as a great American whose memory should be honored, it was nevertheless startling for the head of the Catholic Church to put forward a Baptist minister as a model of virtue.

Speaking of King, Pope Francis praised him for daring to dream, and goes on to say, “I am happy that America continues to be, for many, a land of ‘dreams.’ Dreams which lead to action, to participation, to commitment. Dreams which awaken what is deepest and truest in the life of a people.”

Clearly, for both King and Francis, dreaming is not escapism , something that distracts us from real life, but as Francis points out, a call to action, participation, and commitment. In theological terms, dreaming provides us a vision of the Kingdom of God that draws us onward toward its fullness but which we also embody here and now.

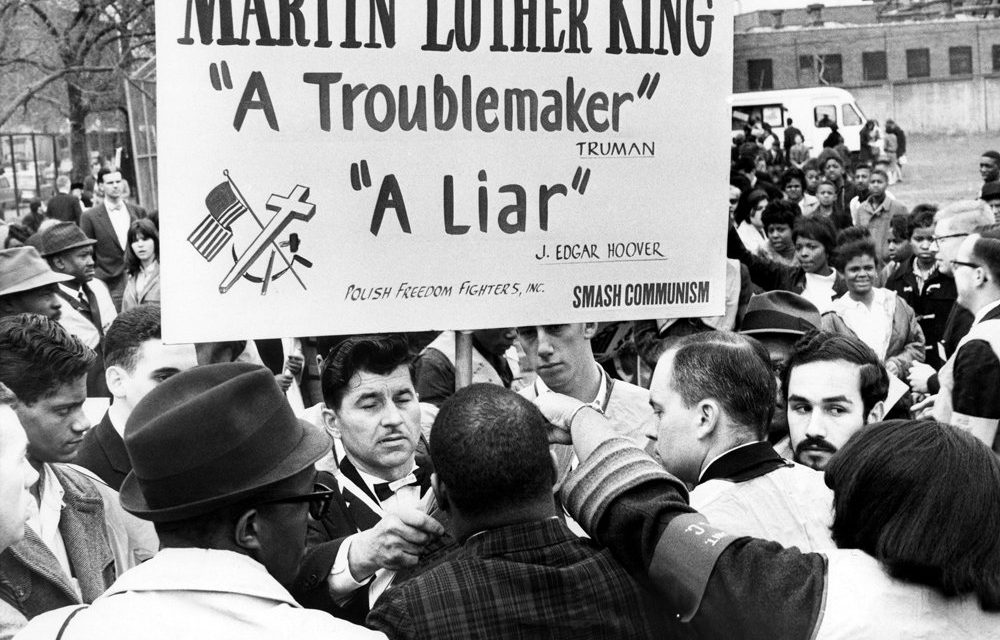

On a day like yesterday when we commemorate King, however, it may be easy for some to forget that his dreaming was necessary because the reality of racism and discrimination was so entrenched. Although he is often thought of as a figure of unity, a “uniter” and not a “divider,” King was in fact a divisive figure in his own time and was reviled by many.

The Gallup organization has helpfully published its own surveys of popular opinion on King during the 1960s. In 1963 and 1964, nearly equal numbers of people had an unfavorable view of him as favorable, and by 1965 those with unfavorable views outnumbered the favorables. In all three years, the number of people with highly unfavorable views of King was greater than those with highly favorable views. By 1966 public opinion had turned decisively against King, with 63 percent of the public having an unfavorable view of him and only 33 holding a favorable view. What happened to turn public opinion against him at that time? This is when King began to more explicitly link the struggle for the civil rights of African-Americans to the issues of poverty and the war in Vietnam.

The other remarkable fact revealed by Gallup is public opinion of King at the time the article was published. In 2011, 94 percent of the public had a favorable view of King while only 1 percent had a highly unfavorable view. After his death, King has become a figure who unites Americans. But the unfortunate fact is this hides from view how divisive he was in his own lifetime.

This notion of King as a unifying figure is sometimes thrown in the faces of activists today, such as supporters of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, who are in contrast seen as divisive. Public polling showing a worsening in “race relations” is seen as evidence that these supposedly divisive activists aggressively seeking racial justice are making the situation worse.

Here we see a phenomenon identified by Jesus, who condemns the scribes and Pharisees for building tombs and monuments to the prophets killed by their ancestors, while putting to death the prophet in their midst (Mt. 23:29-31). Division is not necessarily a sign that things are getting worse; it may be a sign that justice is being done. After all, a workers’ strike is certainly a worsening in labor relations, but it may be the way workers achieve a fairer wage. Jesus himself says, “Do not think that I have come to bring peace upon the earth. I have come to bring not peace but the sword” (Mt. 10:34).

Catholic teaching has at times contributed to this preference for unity over conflict. For example, Pope Francis himself, in the same address, called on Americans to “move forward together, as one, in a renewed spirit of fraternity and solidarity, cooperating generously for the common good.” However, he is also acutely aware that all of the individuals he identified, and in particular Lincoln and King, were engaged in struggles that pitted one American against another, even if the ultimate goal was peace and reconciliation.

That is why it is significant that three of the four Americans identified by Pope Francis—King, Day, and Merton—were outspoken advocates for nonviolence. Even when the times call for struggle, nonviolence is an expression of the hope that the enemy is not defeated or destroyed, but rather reconciled. Martin Luther King’s nonviolence is sometimes used to support the myth of King as a unifier. But as the example of King and other civil rights activists, as well as others like Gandhi in India, illustrates, nonviolence attracts the hostility of others just as violence does. The difference is that nonviolence is a form of struggle in which the goal is the conversion of the enemy.

So as we commemorate the memory of Martin Luther King, Jr., let us, with Francis, remember him as a dreamer who taught us to dream. Pope Francis, in his address, points us toward the dreams of immigrants and refugees and the dream of a world without the death penalty. We cannot imagine, however, that turning dreams into reality will happen without a struggle. King also taught us that sometimes this requires us to be divisive, to suffer persecution for the sake of justice, even to the point of giving one’s life.