When he is expounding the parable in today’s Gospel, Pope Francis vividly challenges us in Fratelli Tutti:

64. Which of these persons do you identify with? This question, blunt as it is, is direct and incisive. Which of these characters do you resemble? We need to acknowledge that we are constantly tempted to ignore others, especially the weak. Let us admit that, for all the progress we have made, we are still “illiterate” when it comes to accompanying, caring for and supporting the most frail and vulnerable members of our developed societies. We have become accustomed to looking the other way, passing by, ignoring situations until they affect us directly.

65. Someone is assaulted on our streets, and many hurry off as if they did not notice. People hit someone with their car and then flee the scene. Their only desire is to avoid problems; it does not matter that, through their fault, another person could die. All these are signs of an approach to life that is spreading in various and subtle ways. What is more, caught up as we are with our own needs, the sight of a person who is suffering disturbs us. It makes us uneasy, since we have no time to waste on other people’s problems. These are symptoms of an unhealthy society. A society that seeks prosperity but turns its back on suffering.

But is this always the case? Do we always identify with those who pass by? Why do we seem to be “good samaritans” some times and not others? Yes, we should avoid seeking to justify ourselves, but we should also recognize that people quite often do come to the aid of someone in distress. There is of course the famous situation of the Bystander Effect, in which bystanders ignore the cries for help of a victim of a violent crime, but perhaps New York City in 1964 was not typical… and besides, subsequent investigation has largely disproven the initial story that gave rise to the idea that so many ignored pleas for help.

So, in many cases, people do in fact seek to come to others’ aid when they are injured. The real challenge this gospel poses is: why do most of us do it some times… and not other times? Why are there cases when we help… and other cases when we pass by on the other side? The reading may give us several hints that will help us understand and overcome our own blindnesses.

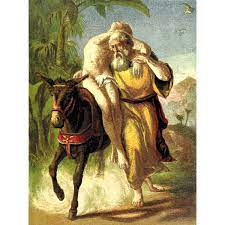

First, the Samaritan is “moved with compassion” at the sight of the robbers’ victim. The phrase, also seen in that other distinctive Lukan parable, the Prodigal Son, marks a clear initial contrast. One sees a person suffering and has varied immediate emotional responses to it. Why do we sometimes feel moved with compassion? What are our other typical initial reactions? The other reactions are likely to focus not so much on the person suffering as on ourselves – whether we react out of fear, out of a sense of being interrupted in our own pursuits, or even out of a sense that the suffering is “their own fault.” If one lives in a large metro area, where street encounters are frequent, I admit my reaction has become one of frustration and bewilderment – why are we as a society so chronically unable to address this problem constructively? Why do our myriad programs seem to miss so many people? This too is not the right reaction. The first reaction should be to the person in front of you suffering.

Second, the story tells us the robbers left him “half-dead” by the side of the road. He was stripped and beaten – in desperate need. It seems fair to recognize that we often make distinctions between people who are in very acute need and others, who may be suffering, but not in such an acute way. The parable, like many of Jesus’ stories, contains stark exaggerations in order to make the point – think of how bad the prodigal son is! So we should recognize that the story isn’t meant to be some kind of calculated casuistry. Nevertheless, we should ask the question: whose acute suffering do I pass by? Whose desperate needs do I ignore? The story is a life-and-death story, and we should ask, what are the true life-and-death situations we ignore?

Finally, the story is awash with identities. Of course, we non-Jewish readers often miss the obvious anti-Temple message of the parable – given that the Samaritans rejected the Jerusalem temple associated with the passers-by! The story is not so much about helping outsiders – it is about supposed religious outsiders helping the suffering, and thereby fulfilling the commandments better, than those focused on correct Temple practice. Jesus gives the “doctor of the law” more than he bargained for here! But the story is clear enough, in prioritizing merciful practice over correct ritual sacrifice – and perhaps more importantly, in focusing on helping those suffering, regardless of various identity claims. What identity claims – especially religious identity claims – may block our response of compassion?

In making these distinctions, I don’t mean to get us off the hook. I just want to recognize that, in most of us, we do in fact help the suffering neighbor… but only sometimes. By recognizing that “sometimes,” we can then pay more attention to what is blocking us from doing it much more of the time.