Jonah 3:1—5, 10

Psalm 25

I Corinthians 7:29—31

Mark 1:14—20

Ethicists tend to evaluate human lives in terms of purposeful decisions or defining qualities acquired through arduous effort. These factors are more readily analyzable and universalizable than coincidental or idiosyncratic actions, and so it is natural to regard them as the primary reference points in a moral history. Yet in the biblical narrative, there is a much more prominent focus on individual moments as explanatory keys for determining the meaning of individual lives. And often, unsettlingly, these moments appear unique and unrepeatable, and thus they elude ethical abstraction and systemization. The entire history of God’s self-disclosure begins with such a moment, when Abraham hears the call to uproot and wander into territory unknown yet promised. The moments then follow one upon the other in a collage of turning points that seem to defy any single ethical pattern or principle. It is therefore not so surprising to find that individual moments, rather than mottos or virtues, often play a decisive role in the didactic fiction of the ancient Israelites.

Let’s be honest: from start to finish, Jonah is never really an admirable character, at least not from an ethical standpoint. He is spiteful, defiant and stubborn. His extraordinary feat is ultimately colored by the bitterness of hatred. To be fair, there are many good reasons for the people of this time to hate the Assyrians, who were arguably the most formidable and ruthless military force in the ancient near east. Yet Jonah’s smug vindictiveness contrasts sharply with God’s mercy, and with the Assyrians’ own humble repentance.

The reading for today tells us that it took three days to walk through the city of Nineveh. Whether or not that is true, the purpose for telling us that fact is to highlight how quickly the transformation of the city took place. “Jonah… had gone but a single day’s walk announcing, ‘Forty days more and Nineveh shall be destroyed’ when the people of Nineveh believed God” and turned from their evil way. There is no effort to convince the reader that this transformation really happened, or that it was really possible; it is presented as a stipulation in order to interrogate the audience: how would you react? What would you do? Would you respond like Jonah? What sort of qualifications and restrictions do you place upon the mercy of God? How wide does God’s mercy extend in your own imagination?

When connected with the gospel passage for this week, however, the impetus of the story seems to shift from this didactic interrogation to a more reflective portrayal of the difference a single moment can make. Jonah does not act out of a settled disposition toward mercy, and yet his reluctant obedience ultimately makes him an incredibly powerful instrument of mercy. One is left only to conclude that it was not so much the power of Jonah’s witness that brought about this change, but rather the potency of the moment into which he spoke his words. The transformation was not the fruit of Jonah’s heart, but of God’s; it grew out of the people’s own barrenness and hunger. To switch metaphors, it was their own dryness and brittleness that accounts for how such a small spark could have brought about such an enormous conflagration.

The occurrence was the fruit of the moment as much as it was the product of a choice or a characteristic. Here we can ponder once again that all-important ancient category of kairos: the dimension of time that is not simply passive succession, but active convergence upon a decisive moment. Too often our ethical models neglect this category; too often we treat human freedom and action as passing through an inert vacuum of moments and circumstances. If the events in our lives have any meaning, we often think, they must have meaning because of the deliberate choices we have made against that inanimate backdrop. Yet for the biblical imagination, it seems to me, time has an agency all its own.

Hence the kairos of the conversion of Nineveh; hence the kairos of the immediate compliance of the first disciples who left their nets by the seashore to follow the Master. In these decisive moments, there rarely seems to be a reflective weighing of the various factors in play. Many of the actions in such moments seem frankly irresponsible or at the very least imprudent. Yet there they are: the moments where an acceptance, affirmation or response changes everything, for everyone.

Mark clearly suggests that the inexplicable moment in which Simon, Andrew, James and John leave everything to give their lives to an untrained wandering rabbi has something to do with “the Kingdom of God.” That is the equivalent in this gospel scene to Jonah’s proclamation; He says it, and they respond totally and wholeheartedly. Unlike Jonah’s words, however, Jesus’ are very much in the present tense: “the Kingdom of God is at hand.” The command, however, is the same: Repent, and believe.

If we try to take on the biblical imagination’s reverence for the active role that a single, unrepeatable moment can play in the life of an individual or a people, we can perhaps appreciate a truth of human experience that bears directly upon the ethical dimension of the Christian life: namely that these two human acts—repentance and belief—really are the work of a moment. They are often compressed to a point in time so small that they seem to occur outside of time.

C.S. Lewis tells the story of boarding a bus as an agnostic and stepping off it as a believer. What happened in that space of time? When on that bus ride did the balances finally tip? Edith Stein relates the story of picking up a book of St. Theresa of Avila as an agnostic, and putting it down as a believer determined to devote herself wholeheartedly to a life of Christian discipleship. When was it in the midst of those words that she actually performed the act of belief? Isn’t it also the case with us as well, that when a long-held belief changes, it does so in an immeasurable instant that is almost impossible to pinpoint? And isn’t it the case that a vital, even decisive factor behind these sorts of changes is the this-ness of the moment in which they occurred?

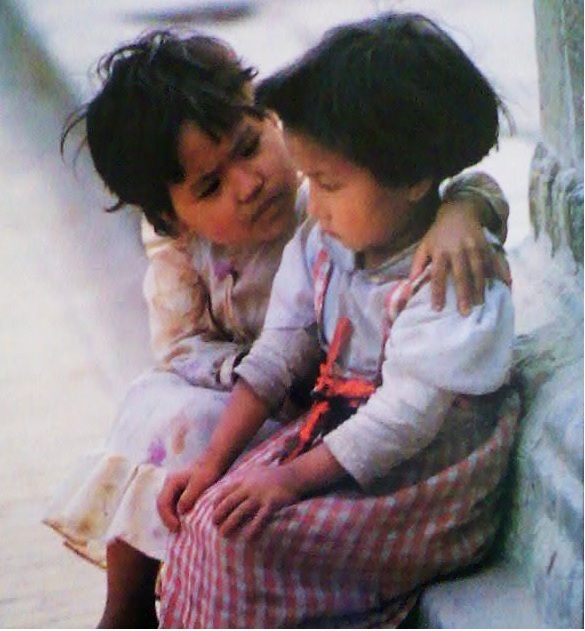

Perhaps the more common experience, however, is the momentary nature of repentance. That repentance is so often described as a “piercing” is no mere artistic convention. Is this not the way we experience it? We pass through an instant and find ourselves open and bleeding in the wake of an apprehension that transforms us, after which we cannot be the same again. And how often is this sort of apprehension the work of a mere word, a mere image?

Moments in time, unrepeatable instants: these are active elements in the drama of salvation. Let us treat them as such. Let us treat every moment—even this very one—as holding the same sort of radical potential. For the Lord of time is always trying to break through time to meet us in unique ways, to draw us out of chronos into kairos, where His kingdom is always at hand.