Pope Francis’ two recent interviews have propelled the papacy once again into the forefront of the media consciousness. Everyone is talking about Francis, and the revolutionary tone he seems to take in his ever-candid responses to journalists. All the major outlets reported with delighted surprise on the pope’s call for the Church to refocus on extending mercy to the wounded rather than simply promulgating “small-minded rules.” Many others were quick to respond that such a comment did not amount to a disparagement of the work of the pro-life movement, and just as many were quick to elaborate upon Francis’ later remark that proselytism was “solemn nonsense” so as to retain some continuity with the Church’s continued emphasis on “the new evangelization.”

Though all concede that Francis has not given any hint in these interviews that he intends to alter any official Church teaching, the hope (or specter) of such a prospect was strong enough to warrant the qualification in almost every news report. The novel and controversial quality of the interviews has led to more stories over the last few days concerning their translation and composition, as well as their status vis-à-vis Francis’ magisterial authority.

In particular, John Allen’s column yesterday reports not only that Eugenio Scalfari’s La Repubblica interview of October 1st was actually a reconstruction of their conversation composed entirely from memory, but also that it contained at least one factual error regarding the given account of Francis’ election. Nonetheless, Vatican spokesman Frederico Lombardi confirmed the substance of the interview, saying that

the text accurately captured the ‘sense’ of what the pope had said, and that if Francis felt his thought had been ‘gravely misrepresented,’ he would have said so.

Readily admitting that the pope’s responses may not have been verbatim, Lombardi explained that the interview “represents a new genre of papal speech that’s deliberately informal and not concerned with precision.”

Of course, the genre itself is not entirely new. As Andrea Gagliarducci of the Catholic News Agency reports, it has become something of a tradition since John XXIII for popes to give interviews to the press and to appear in varied media settings such as TV, radio and (more recently) the Internet. In fact, it was really Pius XII who began this trend by giving his famous Christmas addresses, which many now regard as indispensable contributions to Catholic social teaching. Pius XII went so far as to dedicate an entire encyclical (Miranda Prorsus) to the proper utilization of “the communication fields” of film, radio and television.

The definitive coming-of-age of the genre, however, came with Pope John Paul II’s two book-length interviews, Crossing the Threshold of Hope in 1995 and Memory and Identity ten years later. Pope Benedict XVI also published a book-length interview entitled Light of the World in 2010. Since they are books, these interviews were doubtless subject to considerably more editing and revision than Francis’ recent interviews. They were also composed largely as correspondence over a much longer period of time. Nevertheless, they preserve the basic dialogue format of an interview: the conversation between two individuals prompting and responding to one another’s words.

We saw a preview of the current media frenzy, however, in the fuss they made over Benedict’s remark about condoms. (One wonders what else may have been edited out.) Yet just as was the case with his Regensburg lecture, there was scant effort by reporters to place Benedict’s words within the larger context of the texts from which they came, let alone the larger context of Magisterial teaching. The dangers attendant upon lack of context likewise threaten Pope Francis’ recent comments, given their abbreviated and informal style, not to mention the apparent lack of editorial scrutiny on the part of the Vatican.

To take the most prominent example, a great deal of ink and bandwidth has already been dedicated to dissecting the deeper meaning of his “who am I to judge?” remark. In fact, I’d say more ink and bandwidth has been spent on that line than on the whole of his first encyclical Lumen Fidei. Yet to be fair, there is something beyond the sensational headline-catching lines in Francis’ recent interviews that is deeply compelling to the contemporary world. William G. Ward may have been content with “a papal Bull every morning with [his] Times at breakfast,” but the current online generation may require a different tack.

Is it necessarily an abdication of the responsibilities of the papal office to employ a vehicle of communicating with the world that is “deliberately informal and not concerned with precision”? OK, granted: a lack of precision in itself is never good, but does it necessarily devalue the status of official Magisterial teaching for the pope to share personal encounters with the world of the sort that preclude full theological explanations? Cannot such encounters co-exist with and perhaps even complement the usual times and places where a pope teaches in a more formal and precise mode?

As I mentioned, the genre of the personal interview has been well established in modern times. Their chief value, in my view, is that they give us a clear glimpse of who the pope is as a person. One of the main responsibilities of the vicar of Christ, after all, is to offer a model of personal holiness to the faithful. Given the capacity of modern communications to mediate this witness, why should the pope not offer it in a way that shows him for who he really is as a person?

If John Paul seemed most himself “on stage” before the crowds, and Benedict seemed most himself among his books and papers, this pope seems most himself simply talking to people, one-on-one. In every case, we find the same basic paradigm, one set down for us long ago by St. Paul:

So deeply do we care for you that we are determined to share with you not only the gospel of God but also our own selves, because you have become very dear to us. (I Thessalonians 2:8)

Perhaps the most intriguing and telling part of the La Repubblica interview was the repeated and explicit mention Scalfari made of his embrace with Pope Francis. He mentions it at the beginning, recalling how he asked Francis whether he could embrace him over the phone, and then again at the end, when he says simply “we embrace.” Of what relative value is this embrace compared to the conceptual and rhetorical content of the rest of the interview? Was not the most important part of the pope’s “teaching” in this instance his very willingness to encounter this everyday person—a non-believer—and to engage him in conversation and eventually embrace him as a brother, as one for whom Christ died?

Now let me quickly add: a hug does not bridge or belittle the deep divide between the two figures. A hug does not make the conflict between the two worldviews simply dissolve. If we presume that the holiness of the Holy Father is not something he constantly needs to submit to our validation, does not the embrace reflect the agape that falls like rain on the just and unjust alike? Anyone who sees in this gesture “a separation of God’s holiness and God’s love” obviously does not fully appreciate the holiness that attaches to the very office of the pope. There is a reason, after all, why Scalfari was floored when Francis called him on the phone: he properly recognized the act as one of self-emptying humility.

In this age of instantaneous and perpetual information, theologians often tend to analyze and codify every papal word and policy as though it were either positive divine law in need of organization and implementation or else some secret cipher which we must decode. Yet in Lumen Fidei Francis (via Benedict) writes that “theology is more than simply an effort of human reason to analyze and understand, along the lines of the experimental sciences. God cannot be reduced to an object. He is a subject who makes himself known and perceived in an interpersonal relationship.” Could it be, then, that the Holy Father teaches as much through his own interpersonal relationships as he does through his official pronouncements? Could it be that the economy of divine revelation roots itself first and foremost in the soil of personal interactions rather than ideas or prescriptions?

Writing about the role of faith in the experience of suffering, Pope Francis writes:

Faith is not a light which scatters all our darkness, but a lamp which guides our steps in the night and suffices for the journey. To those who suffer, God does not provide arguments which explain everything; rather, his response is that of an accompanying presence, a history of goodness which touches every story of suffering and opens up a ray of light (Lumen Fidei 57, my emphasis).

One thinks of the bleeding woman in Mark who receives salvation by touching Jesus’ cloak. One thinks of the resurrection appearances in John, when Jesus reveals the central mystery of the faith not through formulas or codes but by coming to his friends in person and breathing on them, showing them his wounds, breaking bread with them, sharing broiled fish with them on the shore. Should we not expect the pope, and all our leaders in the faith, to embody this sort of personal presence and immediate solidarity? Is it not this capacity for authentic encounter that confirms and illuminates the credibility of their teaching?

Speaking of the recent Pope soon to be canonized, Msgr. Lorenzo Albacete once explained:

John Paul II knows that no one reads the encyclicals of a dead Pope. They will die with him. He knows that intellectual arguments don’t persuade, that you have to be given these Pentecostal moments of having been touched by grace. That is why he has taken to the streets, to bear witness to the reality of his faith. His motorcade is a stunning show and he is the drama at the center. It can only last a minute, but you’d think people had ten hours of the most intimate mystical experience. For many people it is that one moment when they say ‘I saw another possibility in life.’ That is why the Pope uses every media toy of our age—CDs, cameras, videos, visits that are beautifully orchestrated.

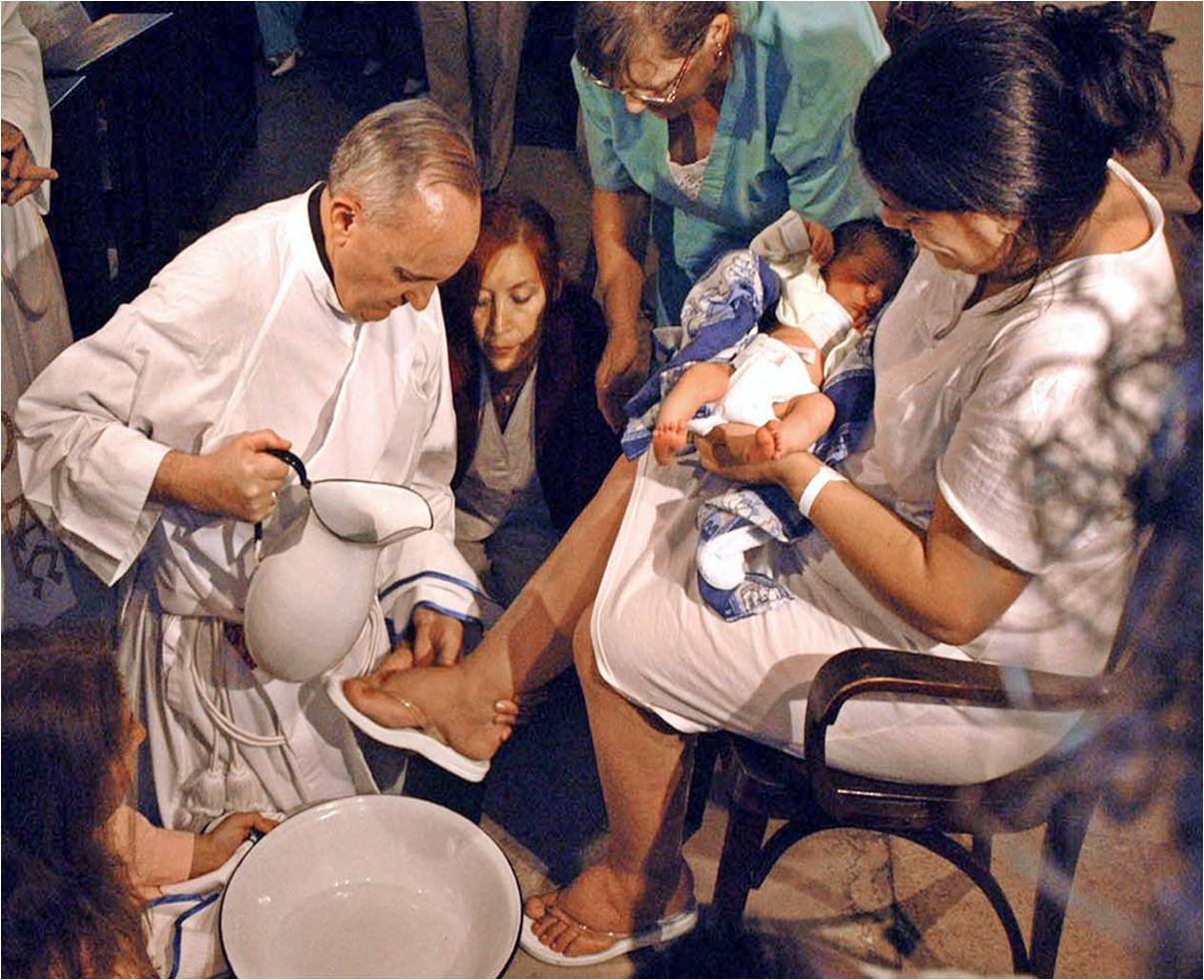

Could we not just as easily apply the same analysis to what we have seen from Pope Francis to this point, replacing the image of the motorcade with the one-to-one interactions for which he is already so well known? Elsewhere Albacete speaks his meaning more directly:

Before being someone with a job to do, [the pope] is the one sent to us to hear, see, and touch, whose physical presence is what links us to Christ. He is the custodian of the Incarnation.

If, as John Paul II himself once wrote, “the kingdom of God is not a concept, a doctrine, or a program,… [but] before all else a person with the face and name of Jesus of Nazareth” then it should not alarm us to discover our pontiff giving witness to that Kingdom in new and surprising ways, the first and foremost of which is his presence.