Psalm 72:1-2, 7-8, 10-11, 12-13

Ephesians 3:2-3A, 5-6

Matthew 2:1-12

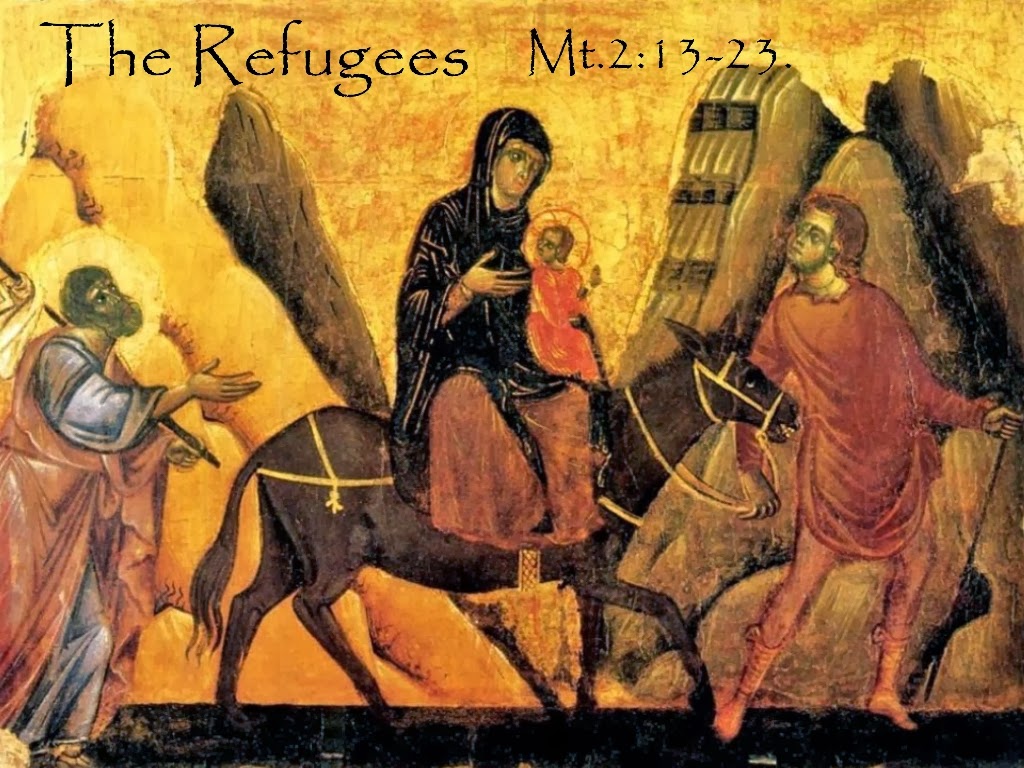

The weeks of Advent this year happened to coincide neatly with some of the most vigorous debating about immigration policy in 2015 in the US, largely due to terror attacks in Paris and San Bernardino. As scores of Syrian refugees sought other lands, and as presidential candidates weighed in on whether to allow or disallow refugees, others posted in their social media images like the following, highlighting the ways the nativity of Jesus features refugees and immigration.

The scriptures we often encounter during Advent and Christmas repeatedly emphasize the dissonance between our proclamation that Jesus is Lord and King, but also the one who is born miles from home in a manger of all places, and who eventually must run, with his family, into exile in Egypt. Some king, with no country and no palace.

Indeed, it is theologically significant that Jesus seeks refuge in Egypt, the land that enslaved his Jewish forebears, the land where the first Passover occurred, the land from which the Jews sought Exodus to the Promised Land. We might even say that without refugee status, Jesus’ own life wouldn’t bear quite the significance that it has.

That story of refuge and exile to Egypt that social media has traded around is a bit hasty, though – just as I think our collective cultural reflections on immigration policy are a bit hasty – for the Flight to Egypt (Matthew 2:13-15) takes place after this Sunday’s gospel- and this Sunday’s gospel is important for setting the context of the Flight – and important for reflecting further on the moral questions we ask in today’s immigrant and refugee crisis.

Sunday’s Gospel tells the familiar story of the Wise Magi, travelling from the East to see Jesus, whom they proclaim as the newborn King of the Jews. Unlike the Luke Christmas account that features a manger scene, shepherds (a lowly profession) and an angel chorus, today’s scripture features Jesus living in a house, Herod’s drive for power, and the latent violence (the slaughter of the innocents) hidden within Herod’s need for power.

Wise people come from everywhere to see him at his home (there aren’t, by the way, only three wise men… the text simply says, “magi”). The Magi traditionally represent different nations; often they are painted as representing different continents. Balthasar represents Africa, Caspar represents Asia, and Melchior represents Europe. Just as today’s Old Testament reading and Psalm have it, all nations come to adore Jesus. The wise people of all nations come bearing gifts and doing Him homage. Thus the Jews become imbued with the glory of the Lord, because Jesus comes as a Jewish baby, who is the light who has come into the world. Epiphany celebrates the many ways God is revealed to us, and here, God is revealed through the Light of Christ that reveals the glory of his nation and people.

It is significant that in this text, Jesus has a home, he has a tradition and culture, and he is not displaced. Here, he is not the one who goes out and encounters us, in all of our different locations and situations (important though that is).

Instead, we come to Him.

We make the response, all of us, to leave our homes. We venture forth and become pilgrims, we become displaced, in order to seek Jesus.

This Epiphany, as we meditate on this particular Gospel account, I think we Christians, especially in the US, might reflect more on the ways Jesus requires us to leave our homes, our places of comfort – and go to places that are uncomfortable, and where we ourselves are displaced. In those places, we shall see Christ.

In addition, if we do not focus enough on the fact that Jesus has a home, a culture, traditions, a family – we do not fully understand the significance of what it means that he also, in the very next verses, becomes a displaced immigrant. He has a home – he will return to a home, but for a time he is in exile. He is not born into a life of exile and endless wandering. He’s got a place – he belongs – just as all humans need a place to belong.

We miss, too, the emphasis that Catholic social teaching has placed on immigration. Being human means needing a place to belong. For example, while social teaching is clear that immigrants are to be welcomed and helped, social teaching also emphasizes the importance of maintaining families and helping people make homes. So often contemporary discussions of policy make it seem that immigrants are perpetually drains on our resources, a kind of permanent unwelcome presence – when in fact, the opposite is true. Regugees and immigrants become important members of our society – and while I think finding a new home when the old must be left behind is difficult -nonetheless many immigrants seek homes, seek places where they do not need to be restless souls.

Immigrants are to be received as persons and helped, together with their families, to become a part of societal life.[644] In this context, the right of reuniting families should be respected and promoted.[645] At the same time, conditions that foster increased work opportunities in people’s place of origin are to be promoted as much as possible.[646](Compendium 298)

So, let us go forth to seek Christ, becoming displaced ourselves as need be in order to follow Him – and seek to make homes for all those displaced souls we encounter