Following is a guest post from Craig A. Ford, Jr., a doctoral candidate and the Margaret O’Brien Flatley Fellow in Theological Ethics at Boston College:

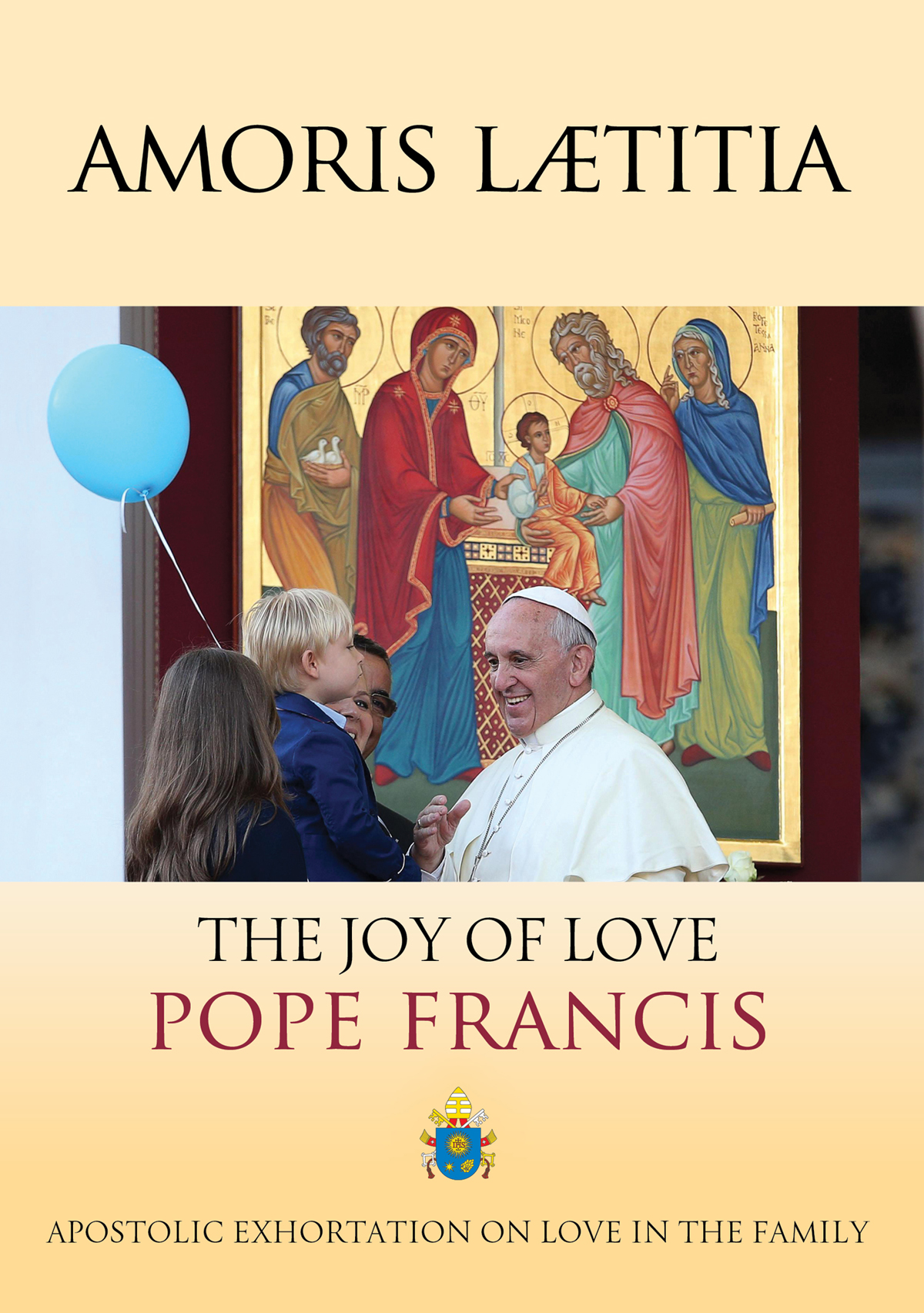

About one month has passed since Pope Francis released his Apostolic Exhortation Amoris Laetitia. As expected, theological commentary has exploded in the same time period. Of course, I make no claim to have read all of the commentary, but I have read quite a bit of it. And, for my part, I’m sad to say how disappointed I am with how many otherwise progressive commentators have engaged the document—and I say this as someone who himself proudly identifies as a progressive.

To answer a preliminary question: how have we progressives tended to engage our critiques of Amoris Laetitia? In my view, we’ve taken some inclusive ideal, noted how Francis nods towards that, and then we proceed to show how that ideal is not fully realized in Amoris Laetitia. Sometimes Francis is not let off the hook—here is where liberal commentators will make statements like, “X should have been included”—though, at other times, liberal commentators offer or imply various reasons—sometimes called ‘pastoral’, other times called ‘practical’—that explain why their ideal was not realized in the document. Here we are meant to understand that the weight of being the leader of a denomination as ideologically polarized as the Roman Catholic Church necessitates prudential trade-offs that make no one happy. According to this perspective, we should, therefore, be understanding about how change occurs in the Church.

What’s interesting to me is that when liberal commentators have engaged either the issue of homosexuality explicitly, or have engaged issues that have a theological relationship to why “homosexual acts” are deemed impermissible (for example, the issue of contraception, which is linked to magisterial teaching on homosexuality because same-sex sex acts, like sex acts involving contraception, are non-reproductive), their engagement has largely been congruent with this latter category, in which our disappointment with respect to development of doctrine on these issues should be tempered by our understanding of Francis’ goals, or by an understanding of Francis’ style, or by the overall context of Francis’ papacy, which James Carroll, among others, has wisely pointed out is less perturbed by how doctrine is worded and more concerned with how it is deployed.

I acknowledge this point, and would tell this to anyone I met on the street or to any of my students in a classroom. I’d also like to acknowledge something else. This sort of reaction to issues involving queer persons is positively insulting, particularly when it comes from queer persons’ strongest allies: presumably straight, well-meaning, liberal theologians.

For one thing, a haunting resonance occurs between, on the one hand, liberal theologians’ call for queer persons to recognize that, as far as Amoris Laetitia is concerned, issues that concern them are “besides the point” or entail a “superficial reading of the document,” and, on the other, these words of Pope Francis:

There is a failure to realize that only the exclusive and indissoluble union between a man and a woman has a plenary role to play in society as a stable commitment that bears fruit in new life. We need to acknowledge the great variety of family situations that can offer a certain stability, but de facto or same-sex unions, for example, may not simply be equated with marriage. No union that is temporary or closed to the transmission of life can ensure the future of society (AL 52).

The resonance occurs precisely insofar as the significance of queer intimacies, particularly those that embrace a dual-spouse, monogamous form, are dismissed. This happens, though, for different reasons: liberal theologians do it so that they can make a greater point about the theological arc of the progressive future towards which Francis is (hopefully) steering the church, and Francis does it so that he can point back to the mythical gender essentialist theological anthropology of John Paul II like that seen in his Theology of the Body.

There is no dodging this latter point about Francis. To confirm it, all you need to do is look at the more narrative-like first chapter of Amoris Laetitia—the one we liberals aren’t quoting. Francis writes, concerning the relationship between Adam and Eve, and from them to all heterosexual couples,

The very word “to be joined” or “to cleave,” in the original Hebrew, bespeaks a profound harmony, a closeness both physical and interior, to such an extent that the word is used to describe our union with God: ‘My soul clings to you’ (Ps. 63:8). The marital union is thus evoked not only in its sexual and corporal dimension, but also in its voluntary self-giving in love (AL 13).

The tentacles of this heterosexist theological anthropology continue to darken the document’s light at other points as well. While liberal theologians are all too aware of the reality of patriarchy in the construction of gender roles, we have let lines like this pass us by on the arc to the progressive future, “It is true that we cannot separate the masculine and the feminine from God’s work of creation, which is prior to all our decisions and experiences, and where biological elements exist which are impossible to ignore” (AL 286). And even if we should admit, and rightfully so, that the next line in the text is “But it is also true that masculinity and femininity are not rigid categories,” we should bear in mind that Francis explores the fluidity of masculinity and femininity along the rather rudimentary axis of the division of household chores. Whatever advance this is—and I speak here from within and to the context of American Catholicism in 2016— I must confess that I hardly see it as “a radical shift in tone regarding gender and feminism.” Lastly, seated comfortably on the progressive arc of history we liberals have, shockingly, decided not to critique Francis’ deployment of what is used to malign the entire field of gender studies—the term ‘gender ideology’. Instead, we sit by with great hope and expectation while Francis and other bishops continue to shame and marginalize the beautiful existences of trans- and genderqueer persons:

It is one thing to be understanding of human weakness and the complexities of life, and another to accept ideologies that attempt to sunder what are inseparable aspects of reality. Let us not fall into the sin of trying to replace the Creator. We are creatures, and not omnipotent. Creation is prior to us and must be received as a gift (AL 56).

All this involves liberal theologians in a remarkably disappointing—though, in my weaker moments, I’ve used the adjective ‘offensive’—complicity with a heterosexist theological anthropology that bears fruit in an equally heterosexist theology of marriage and the family.

What has happened? Have straight, liberal Catholic theologians gotten so used to worshipping with queer persons and their families that their presence at mass is now taken for granted beneath the liberal simpatico that church teaching regarding queer sexuality is bogus? Do straight liberal Catholics know enough queer Catholics who have decided not to abandon the denomination that it’s now okay to say that their concerns are “besides the point” in a document that, actually, directly pertains to them? What sort of display of solidarity is this? The entire point of the preferential option for the poor and vulnerable is to remind all Christians that, among others, the concerns of queer persons are never beside the point.

I do not want to minimize the major interventions of Francis’ document. After all, it is a great moment in our ecclesial life to see a noninfantilizing theology of conscience foregrounded alongside a commendation of working towards integration and communion among the people of God—whether we are divorced and remarried or not. To see these perspectives written “from Rome,” as it were, is worth celebrating.

But it’s important to celebrate it with perspective. Let’s not forget that many liberal heterosexual Catholics have been living a life of conscientious objection from magisterial teaching concerning contraception, premarital sex, and receiving communion after remarrying in partnership with sensible priests in merciful parishes, perhaps even for decades. Though I would not perhaps have put as sharp of a point on it as she does, Mary Hunt is not wrong when she writes, “Certain pastoral decision-making is kicked downstairs to priests and bishops, but that is effectively how things work now. Theology follows practice.”

Once again, my point is to celebrate with perspective and with a sense of solidarity. But so far this has been a party only for heterosexuals, and what is disappointing is that liberal Catholic theologians—who proclaim our consciousness of marginalized peoples as such an asset in our theological writing—have not indicted the core of our Church’s heterosexist theology of marriage in our commentaries on Amoris Laetitia. The Left has allowed, in other words, queer persons and their intimacies to sink farther back into a sort of theological eschaton in order to praise, however measuredly and momentarily, a heterosexist ideal that requires the displacement of queer lives in the first place.

Because of this complicity of the Left, queer persons and their intimacies have become ironic symbols of one of the less popular sayings of Christ about marriage: that in heaven, while there will be love among persons, no one will be married. This complicity has pushed back, that much farther, the institutional celebration of the beauty of queer relationships. After one month of commentary—no matter how beautiful or resilient they are, apparently—queer relationships seem to be beside the point.

I think the central idea of this essay is contained in this statement: “what is disappointing is that liberal Catholic theologians…have not indicted the core of our Church’s heterosexist theology of marriage in our commentaries on Amoris Laetitia.”

It seems there are only two possibilities here: either the Church’s teaching on marriage is a whole cloth invention of her hierarchy, or it is not her plan but God’s plan. That is, either the church has rightly divined God’s mind on the matter, or she has no clue.

The problem with assuming, as the author does, that the church has it all wrong is that it denies some of the fundamental tenets on which she bases her existence…such as this:

If the church’s teaching on marriage is merely heterosexist bigotry she can hardly be said to have authentically interpreted God’s law, has obviously failed her mission, and is not who or what she claims to be.

Wow. This is a perspective I never run into. Amoris Laetitia is “heterosexualist”? This is the equivalent of racist I suppose, but are we supposed to now recognize and condemn “heterosexualism” whereever we see it? And liberals are betraying gays – “queers” – by not objecting that Amoris Laetitia doesn’t even mention homosexuality? That’s harsh. As near as I can tell (haven’t read it) Amoris Laetitia is “besides the point” on homosexuality. This blog entry seems like it was written by a pouty child who wasn’t recognized as special as he or she believes he is. In a world where everyone is above average, every kid gets a trophy, people get mad that a Vatican document doesn’t say everything they want it to say. (BTW, there are a lot more polygamous marriages in the word than same-sex ones, and as far as I know Amoris Laetitia doesn’t mention them, either.)

I find the aggressive use of the term “queer persons” demeaning to our common humanity. Its an attempt to prioritize some persons sexual proclivities above their human nature. It is certainly contrary to Catholic Moral Theology.