This Sunday’s readings may be found here at the USCCB’s website.

Lectionary: 107

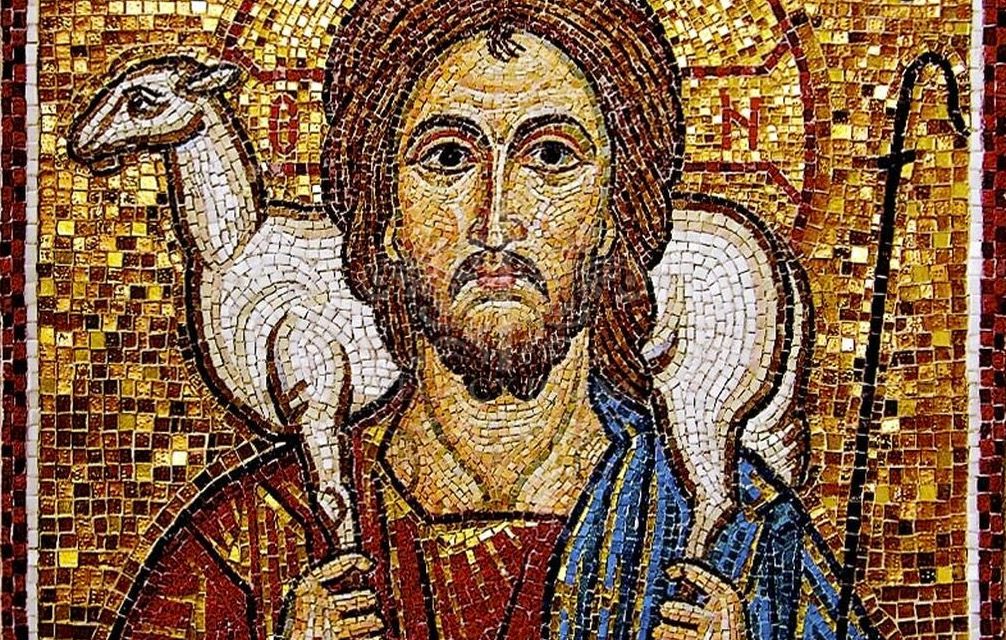

Biblical references to sheep and shepherds number in the hundreds, and appear throughout the entire biblical text. From the primordial stories of Genesis that identify Abel as a “herder of flocks” (4:2), to the culminating vision of Revelation that depicts a slain “lamb” as at once a shepherd, a bridegroom, and a king (7:17; 21:9,22), references to sheep and shepherds appear and reappear at every turn in the Bible. While it is surely the case that the frequency of these references tells us something about the central place of sheep in the culture and economy of ancient Israel, the significance attached to shepherding is much deeper than other similarly appropriated aspects of Israelite life. At its most critical points, the Biblical drama portrays images of shepherds and sheep, and seems to invest much in their mutually dependent relationship.

The relationship between shepherds and sheep is asymmetrical by definition, even if it is true that the shepherd depends for his survival upon the sheep in his care. The sheep depend upon the shepherd in a much more immediate and radical way: without the shepherd, sheep simply don’t know what to do or how to get along. Over millennia, humans have domesticated sheep to the point where shepherds are as essential to their survival as food and water. Indeed, sheep depend upon shepherds in order to find their food and water. Without shepherds to guide them, sheep are quite literally lost- aimless, afraid, and ultimately doomed.

I myself am not a shepherd, although my family currently cares for 23 chickens, 8 ducks, 2 cats, and a dog. The chickens are probably closest to sheep in terms of dependence, but certainly not as high maintenance. My knowledge of sheep and shepherding is limited to the personal testimony of others, as well as written accounts in books. Particularly illuminating is W. Phillip Keller’s 1970 book, reprinted in 2007, called A Shepherd Looks at Psalm 23. Keller was born in Kenya, the child of Christian missionaries, and learned the practice of shepherding there alongside native shepherds who still took care of their flocks in much the same way as the ancient Israelites. While Keller carried a rifle with him in the fields, many of his neighbors still carried traditional knobkerrie clubs, surely much closer to what Psalm 23 had in mind when referring to “thy rod.” Keller offers a plethora of similarly pertinent observations about shepherding, both ancient and modern, in direct reference to the six well-known verses of David’s emblematic prayer. Yet these facts only sharpen the resolution of the central insight which the Psalm makes plain in its opening lines: “The Lord is my shepherd.”

Throughout Keller’s book, he presents a strong case for the standard assumption that the author of this Psalm must have had considerable experience caring for sheep. Just to be sure we know, perhaps, the text identifies itself as “a psalm of David.” Like Moses before him, David was a shepherd. David knows what it is like to take on this thankless responsibility of caring for sheep: alone for weeks or months on end, exposed to the elements, a magnet for predators. From this position, or perhaps reflecting back upon it, David expresses in various ways a single idea: “I too have a shepherd” or more accurately “I too need a shepherd.” Above all then, the psalm is an expression of dependence, a confession of individual need and a declaration of confidence in another’s provident care. The relationship that creates and defines the shepherd is one of dependence and provident care, and in this psalm it is the shepherd himself who recognizes and affirms his own subordinate place in such a relationship.

This week’s first two readings, from Jeremiah and Ephesians respectively, drive home the point that such relationships are not merely a matter of affection and concern, but also obligation and justice. At the end of his ninth sermon, Jeremiah delivers a warning to the kings of Judah:

Woe to the shepherds

who mislead and scatter the flock of my pasture,

says the LORD.

Therefore, thus says the LORD, the God of Israel,

against the shepherds who shepherd my people:

You have scattered my sheep and driven them away.

You have not cared for them,

but I will take care to punish your evil deeds.

Through the prophet, the Lord cries out against the kings because they have abdicated and abused their leadership obligations. They were called to lead the people as a shepherd leads his flock, but they have driven the sheep away and failed to care for them. The Lord declares that he himself will act as the people’s shepherd, gathering what is left of them by means of “a righteous shoot of David” that He will appoint as their new leader. The people will bestow upon this appointed shepherd the name “the LORD, our justice.” Notice, they will not call him “the Lord, our kind and affectionate caretaker”; the reestablishment of right relationship between the king and his people is a matter of the Lord’s justice. In other words, the shepherd-model of leadership is not just an ideal that will help the people to see God’s own particular mode of sovereignty; it is a requirement of the order of justice. When a shepherd does not recognize his own need for a shepherd, it is not just a suboptimal state of affairs; it is an abomination that cries out for God’s justice.

The dependence and care constitutive of a shepherd’s relationship to sheep is therefore more than a handy metaphor. It tells us something about the order of creation. Authority is part of God’s order for the world, but only if it embodies the dedication and self-sacrifice of the shepherd. And as St. Paul makes clear in his letter to the Ephesians, the ultimate end of such authority is peace. Yet the peace of the Good Shepherd is not merely the restraint of opposing forces or the balancing of tensions, but union. The true Shepherd lays down His life for the sheep in order that they might be united to Him and in Him. As the final vision of the “lamb shepherd” in Revelation suggests, the asymmetrical dependence of authority is ultimately meant to give way to self-emptying identification and mutual communion. True biblical leadership is therefore first and foremost a “shepherding” of this kind.

In this week’s gospel, we see Jesus clearly trying to get away from “the flock,” directing the apostles to come away with him to “a deserted place.” All parents (shepherds of families) can identify with Jesus here; sometimes you just need a moment away to regroup. But the crowds follow Jesus, and await him expectantly when He arrives at his retreat. Mark then says that

When he disembarked and saw the vast crowd,

his heart was moved with pity for them,

for they were like sheep without a shepherd;

and he began to teach them many things.

What was it exactly that moved Jesus’ heart with pity here? What was it about shepherdless sheep that is so pitiful? The experience of shepherding is again apt. Keller’s own recollections reiterate the point that sheep need not merely the protection and provisions that shepherds provide, but the presence of the shepherd himself. Sheep are skittish creatures; they cannot eat, drink, or lie down unless they feel completely secure. Even conflicts within the flock put them on edge, and effectively paralyze them. So it is with us: it is not enough that the Lord dole out our necessities to us; we need His presence. We need Him. Likewise, it is not enough for us to exercise our own authority from a distance; above all, those who rely upon us need the nourishment of our presence in order to perceive the direction and purpose of our care. For as the biblical model of the shepherd teaches us, the ultimate end of authority is not survival but communion. And this communion is ultimately a matter of justice, since it is the heart of God’s intended order for creation. The true king of the world is the One who emptied Himself and gave His life for all. Our true shepherd is the Lamb.