Acts 4:32-35

Ps 118:2-4, 13-15, 22-24

1 Jn 5:1-6

Jn 20:19-31

In our first reading from the Acts of the Apostles, we have an image of the ideal church:

The community of believers was of one heart and mind,

and no one claimed that any of his possessions was his own,

but they had everything in common. . .

. . . There was no needy person among them,

for those who owned property or houses would sell them,

bring the proceeds of the sale,

and put them at the feet of the apostles,

and they were distributed to each according to need.

Luke shows us how the infant church has taken seriously the demands of discipleship to “go and do likewise” (Luke 10:37). They are united in love and service. Whatever hierarchy exists does not lead to the marginalization of the poor and weak. The community is marked by peace, cheerful self-sacrifice, and joy.

This passage begs a certain nostalgia from us a Christians today, living in a church marked by strife, gross inequalities between the rich and poor, and a certain wariness and weariness. “Wouldn’t it be great,” we might think, “if we could just recreate the 1st century church?” We have to be careful, however, extrapolating from Luke-Acts any uniform image of the 1st century church. After all, Paul’s letters, which are chronologically earlier, paint a very different image marked by a level of conflict and scandal possibly rivaling what we see today (e.g. 1 Cor. 5:1-13).

This reading is not given to us to make us nostalgic for a better time in Christian history. In all likelihood, there probably never was a better time. The church is an all-too-human institution, marked by all of our all-too-human faults. On this second Sunday of Easter, Divine Mercy Sunday, we are given an image of what the church is called to be and what the church can be, even though she always falls short.

The church is called to be merciful. “The sum total of Christian religion, as regards external works, consists in mercy,” Aquinas tells us (II-II, Q. 30, a. 4, ad. 2). Mercy is the virtue that moves us to feel the distress of a brother or sister and seek to relieve that distress. It is mercy which marks the “Good Samaritan.” The church is called to mercy because she has been shown such great mercy by the one who is Mercy.

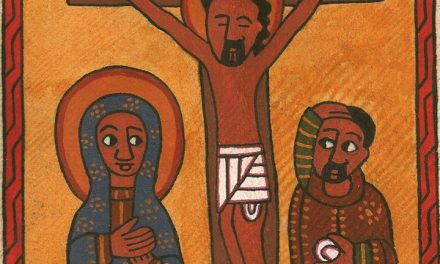

We experienced the mercy of Christ in the Easter vigil in the sacrament of baptism and we continue to experience the mercy of Christ every time we go to mass in the most holy sacrament of the Eucharist. But in a very special way, the mercy of Christ is manifest in the sacrament of penance. Christ knew he was leaving his church in the hands of flawed men who would be the leaders of a flawed church. For this reason, in part, he gave the church the healing sacrament of penance for the ongoing forgiveness of those sins which lead to death:

Jesus said to them again, “Peace be with you.

As the Father has sent me, so I send you.”

And when he had said this, he breathed on them and said to them,

“Receive the Holy Spirit.

Whose sins you forgive are forgiven them,

and whose sins you retain are retained.”

In confession, we encounter Christ who stands lovingly ready to forgive us our faults. And as we experience the mercy of Christ in confession, we in turn are given the grace necessary to be the ones who show mercy, to forgive as we have been forgiven. The sacrament of confession is integral for the Christian moral life not only because of our own moral failures, but also because the grace we receive there helps us to bear the moral failures of our brothers and sisters in Christ.

On Divine Mercy Sunday we are reminded of the great blessing that confession is. Like the Eucharist, it is where we encounter Christ in faith and are sent forth to encounter our neighbor in love. And it is a sacrament of healing for the church as she strives to make Christ manifest in the world through her actions.