At a recent conference, someone commented that one task of today’s theologian is to review Vatican II and the implementations and other changes made in the years following this council. Among these changes was one that resulted in a drastic decline of penitential culture in the United States. This was precipitated by an apostolic constitution of Blessed Paul VI, who wrote Paenitemini with the hope that local bishops would be able to renew the practices of penance in their respective locales. An updating of such practices, it was hoped, would bring penances more directly related to (and appropriate for) the situation of the faithful in particular places, rather than prescribing (as canon law did) a one-size-fits-all obligatory penance.

In the United States, the National Conference of Catholic Bishops wrote a letter establishing new guidelines for penance, which were implemented in Advent of 1966. Among the required penance that was altered for the faithful was the practice of Ember Days. Due to this change in 1966, most post-Vatican II Catholics are altogether unfamiliar with Ember Days. This time of year, however, people will occasionally mention the practice, and there are a few who still choose to observe Ember Days.

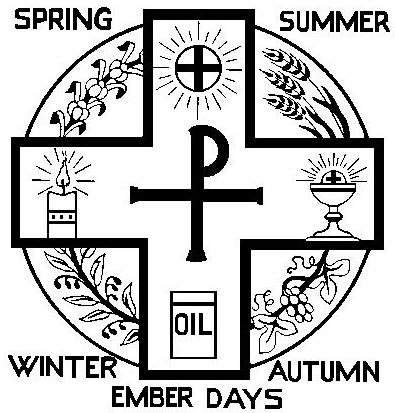

Ember Days represent a classic re-appropriating of the pagan culture, as they were a way to sanctify the pagan rituals associated with the seasonal changes related to planting, harvesting, and vintage. The western Church expanded these rites from three to four times a year and made them special days to thank God for gifts of nature, pray to make use of them in moderation, and to help the needy who lacked such resources. A further development was to offer prayers with those preparing for ordination to the priesthood.

The practice of Ember Days consisted of fast and abstinence from meat on one Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday at each of these four times of the year: after the Exaltation of the Holy Cross (fall), after the Feast of St. Lucy (winter), after Ash Wednesday (spring), and after Pentecost (summer). Liturgically, the associated prayers had a penitential tone, and ordinations of priests generally occurred at the completion of Ember Days.

In the wake of Vatican II, Ember Days were easily dismissed in the United States, perhaps for two reasons. First, the Church was no longer enmeshed in an agrarian society. Many of the faithful had little or no experience of planting, harvest, or vintage; they were largely disconnected from their food and the work that went into getting it to their table. Secondly, with a Vatican II theology noting the “universal call to holiness” and using the phrase “the People of God,” it may have seemed unnecessary or counter-intuitive to offer special prayers for those about to be ordained to the priesthood.

Interestingly, we now face a situation where we can acknowledge two crises with respect to the Church in the United States. On the one hand, many of us are concerned with environmental issues, and on the other hand, we have been dismayed about the scandal among clergy and their leadership. Now might be a good time for theologians to reconsider this removal of Ember Days from the liturgical calendar and to consider voluntarily observing these days.

The fall Ember Days are this Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday, and, since observation is not obligatory, we might consider doing one (or more) of these acts: 1. abstaining from meat on these days, 2. not eating between meals on these days (or practicing a “Catholic fast,” with one full meal and two smaller meals), 3. attending daily Mass on these days, 4. offering extra prayers for bishops, priests, seminarians, and deacons, 5. almsgiving to assist those who are hungry and lack food, e.g. donating to a parish food pantry, 6. choosing another act of penance for our misuse of God’s gifts.