In The Screwtape Letters, Uncle Screwtape advises his tempter-demon nephew Wormwood that,

The real trouble about the set your patient is living in is that it is merely Christian. They all have individual interests, of course, but the bond remains mere Christianity. What we want, if men become Christians at all, is to keep them in the state of mind I call “Christianity And.” . . . . If they must be Christian, let them at least be Christians with a difference. Substitute for the faith itself some fashion with a Christian coloring. (Letter 25)

Screwtape wants people to turn their faith into something divisive, something that sets them and their beliefs off from others. The fallout from Pope’s Francis recent interview makes it seem that Pope Francis is doing just this. Slate magazine, for example, claimed he was “a flaming liberal”. I agree with so many others who insist that this is not what Francis is doing (a point effectively made by Charlie Camosy, Mark Shea, and many others.)

What is the Pope doing? Francis seems to be addressing not a left-right problem but an inside-outside one. Our church is afflicted by groups—and they can be from the right, middle, or left—that use one aspect of the gospel as a shibboleth to distinguish the inner circle from the outer, the righteous from sinners, and the justified from the damned. Pope Francis seems concerned with bridging these divisions (the pope is supposed to be the pontifex maximus, the ultimate bridge-builder, after all) by focusing on the faith behind all of them.

But the proclamation of the saving love of God comes before moral and religious imperatives. Today sometimes it seems that the opposite order is prevailing. . . . The message of the Gospel, therefore, is not to be reduced to some aspects that, although relevant, on their own do not show the heart of the message of Jesus Christ.

And again . . .

This is pure Gospel. God is greater than sin. The structural and organizational reforms are secondary—that is, they come afterward. The first reform must be the attitude. The ministers of the Gospel must be people who can warm the hearts of the people, who walk through the dark night with them, who know how to dialogue and to descend themselves into their people’s night, into the darkness, but without getting lost.

For Francis, this “saving love of God” and “pure Gospel” is what binds us all in communion with one another and together with God.

Belonging to a people has a strong theological value. In the history of salvation, God has saved a people. There is no full identity without belonging to a people. No one is saved alone, as an isolated individual, but God attracts us looking at the complex web of relationships that take place in the human community. God enters into this dynamic, this participation in the web of human relationships.

This is Pope Francis’ mere Christianity: it is a focus on God’s love and the way this love unites us with each other. It runs through his interview but also through his first encyclical. In Lumen Fidei, he writes that “Christian faith is thus faith in a perfect love, in its decisive power, in its ability to transform the world and to unfold its history” (§ 15), and it is this “perfect love” that binds us together.

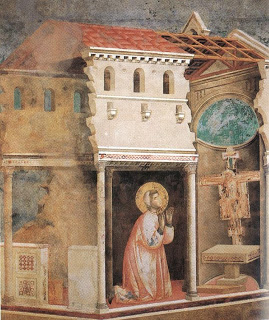

The transmission of the faith not only brings light to men and women in every place; it travels through time, passing from one generation to another. Because faith is born of an encounter which takes place in history and lights up our journey through time, it must be passed on in every age. It is through an unbroken chain of witnesses that we come to see the face of Jesus. (§ 38)

I am not claiming that this situation is something new nor that Pope Francis is doing something unique. He seems to be addressing a problem the Church has faced from its beginning and is responding in a way that the Church has frequently responded. Jesus told his disciples the parable of the tax-collector and Pharisee (Luke 18:9-14) to warn them about using religion to justify one’s self. To the church at Corinth that was mired in divisions based on status, wealth, and spiritual gifts, St. Paul reminded them that they are all parts of one body that should be united by love (1 Corinthians 12:12–13). St. Irenaeus responded to the Gnostics, who insisted that only they were saved because only they had the special knowledge, by insisting on the catholicity of salvation.

Pope Francis’ “mere” Christianity should challenge us. We should neither cheer nor bemoan the perception that one side is favored over another (as Rebecca Sharbaugh indicated in her reflection on the pope’s interview). We should hear the “pure gospel” about the “perfect love” and “saving love” of God as a demand placed upon our labors. We should see other people and their work just as we see our work and ourselves: as genuine attempts to do God’s will. Let us hope we can become a little like the set Wormwood warned against: “have individual interests, of course, but the bond remains mere Christianity.”

This post is the second in a series of posts reflecting on the interview “A Big Heart Open to God” with Pope Francis published in America Magazine and simultaneously in 15 other Jesuit Magazines around the world.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks