As a cradle Catholic raised in the post-Vatican II era, I began lectoring alongside my dad at my local parish at the young age of 12. The diocese of Des Moines must have been behind the rest of the U.S. because girls were not yet allowed to be altar servers in the 1980s. I never minded that; I preferred to lector. And when I attended the University of Notre Dame, I became the liturgical commissioner for my dorm, in charge of scheduling presiders and training lectors, and yes, I was now responsible for serving at Mass. I also was privileged to lector at the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, and I credit the rector Fr. Peter Rocca for improving my skill at the ambo – “louder, slower, louder, slower,” were the constant reminders that stuck with me for years to come.

After college, as a young singleton living in southern California, I continued to lector and to be a Eucharistic minister. And when I moved to Ohio to begin graduate school, I made sure to get on the Sunday lector and Eucharistic minister rotations at my new parish, as well as at the University of Dayton chapel for the daily 12:10 Mass.

Then I got married, and one month before our first wedding anniversary, we were joined by a child. Suddenly, I was off the list for these duties that had been such a regular part of my life. I found myself stuck nursing a baby during Mass, listening in agony as the lector mispronounced difficult words and watching as a Eucharistic minister fumbled some hosts. Even worse, my husband was able to continue as a Eucharistic minister and lector, since the baby always wanted me. He tried to get off the schedule so we could share duties in the pew with the fussy newborn…but then five minutes before Mass someone would approach him and ask that he replace a no-show lector, and I was – once again – left alone to fend for myself.

I didn’t know it at the time, but this was to be the new norm for me – thirteen years and six babies of being confined to a pew during Mass. Swaying, shushing, nursing, glaring, hugging, rubbing backs, tying shoes, and of course, frantically escaping to the back of the church during the consecration as a child began screaming.

For years, I had been a clearly contributing member of my church during Mass. Now I did nothing. At least, that’s how it felt.

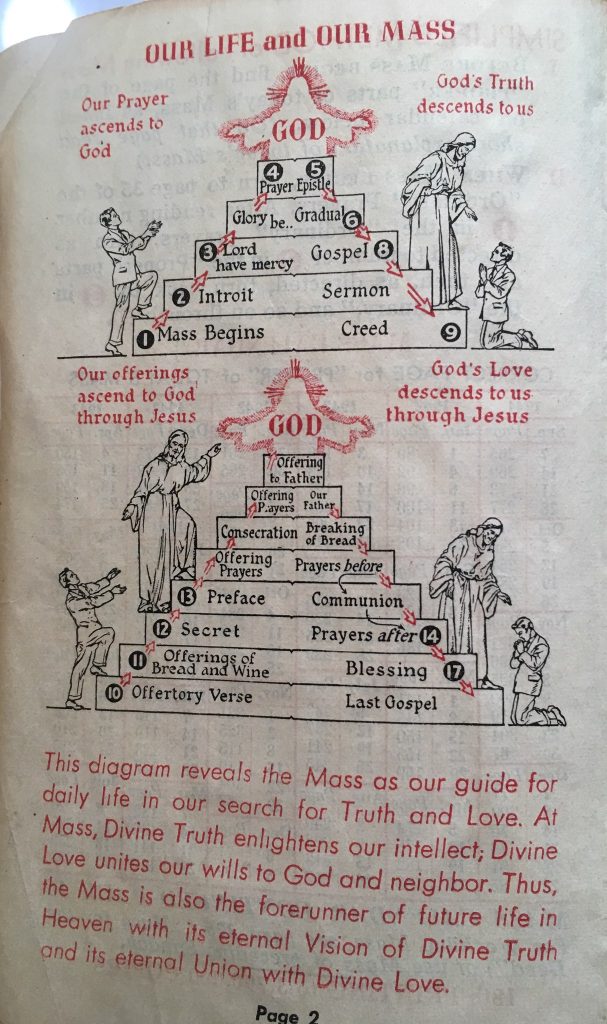

Providentially, though, I had taken a liturgy course while pregnant, and my newfound relegation to the pew caused me to reflect on that course. I had the sudden realization that I was still able to have – in the words of Sacrosanctum Concilium from Vatican II – “fully conscious, and active participation” in the Mass (no. 14). After all, participation in the Mass wasn’t about lectoring, serving, or being a Eucharistic minister. It was about praying!

I’m sorry to say that it took me to motherhood and almost-30 years old to realize that the Mass is about prayer. I guess I missed all the times the priest said, “Let us pray.” I was too busy thinking about what a great lector I was. And that attention to the show on the stage – and my important role in it – actually distracted me from the participation in the Mass to which we are all called. That participation is one of worship, praise, gratitude, and prayer. And, much to my relief, it can be done from any position in the church; one needn’t be in proximity to the altar.

Pia de Solenni’s recent piece in America, “What the debate over deacons gets wrong about Catholic women in leadership,” suggested that our current conception of leadership in the Church is too limited. Laity, both men and women, contribute in many ways to building up the kingdom.

Of course, de Solenni’s deemphasis on female lay leadership in the church might seem hypocritical. After all, as she notes at the outset, she is the “chancellor of one of the largest dioceses in the country and fourth on the organization chart for the Diocese of Orange.” De Solenni is the outlier, the rare female with acknowledgeable and undeniable leadership in the church.

I write, then, to corroborate her words. My work these days is less academic/theological and more in the realm of laundry, dinner, and Legos. I have no prominent leadership role in the Church, and perhaps that’s why I now find her words so convincing. De Solenni states: “While the church certainly needs competent lay women and men in leadership roles, we need exponentially more competent lay women and men living out every aspect of their lives influenced by their faith and an authentic understanding of the dignity of the human person.”

Just as I failed to recognize for years that the real work of the Mass is prayer, we often fail to acknowledge the real work assigned to us as the laity in the world. We care too much about who is in the spotlight. I frequently witness an attitude that rejects the tough work given to us as laity. We prefer to debate about it at theological conferences and argue about it in Twitter spats.

But, on the other hand, I also have the opportunity to see the leadership that de Solenni regards as important. Among my female Catholic friends are doctors, lawyers, professors, social workers, nurses, teachers, accountants, and many more. In the midst of this work, they bear witness to the faith and influence the culture. In any given week, I have the opportunity to gather with women praying the Rosary together and supporting each other in living a Catholic life in a secular world. I can attend Catholic discussion groups of readings on topics important for our families and society. I am able to hear talks given by women with great insight about strengthening prayer life and family life.

They aren’t famous; their names are unknown outside of small circles of friends and acquaintances. Their leadership is not the kind that people celebrate or envy. And yet, they are living the kind of leadership that de Solenni describes. As she says, they “need no title, besides Catholic, to do so.” Moreover, I know the women and men trying to raise their children in the faith in a world that is increasingly hostile to it. They are committed despite the struggles. It is encouraging that Solenni recognizes the value of the influence of parents. In a Church where it is easy to become focused on who’s at the altar and judge accordingly, Solenni’s piece is a great reminder of the important daily work that we are all called to do.