The lectionary readings for Ash Wednesday can be found here.

Joel 2:12-18; Psalm 51: 3-6, 12-13, 14, 17; 2 Cor 5:20-6:2; Mt 6: 1-6, 16-18

Lent is a season of mercy. In today’s first reading, the prophet Joel reminds listeners that God is “gracious and merciful,” “slow to anger, rich in kindness, and relenting in punishment.” We, God’s people, are invited to return to right relationship with God. The Psalmist petitions God for mercy and forgiveness, after acknowledging one’s sin and seeking “a clean heart” and “the joy of your salvation.” The second letter to the Corinthians focuses on the reconciliation Christ initiated. And in Matthew’s gospel, we see Jesus condemning hypocrites who pray to be seen praying. Better are those who pray “in secret” and do not change their outward appearance while fasting. As we begin the season of Lent and reflect on these readings for Ash Wednesday, some themes emerge from the discipline of Christian Ethics with regard to sin-talk. These can help shape our Lenten practices as we consider the most appropriate spiritual goals for our journey to Easter.

Sin as Rupture of Relationship

An early biblical understanding of sin, as we see in today’s readings, is a weakening of one’s relationship with God and with the community. Historian Joseph Martos explains that an early understanding of sin in the Christian theological tradition was “a break in the relationship of love and trust between members of the community, and as a violation of the covenant relationship between the community and God.” Later, it was unfortunate that sin came to be collapsed with “violation of an ecclesiastical law,” which further clericalism and legalism in Christian spiritual practices (Doors to the Sacred, 278). Spiritan Fr. Richard M. Gula elaborates: “When taken to the extreme, sin became a transgression of a legal code rather than a failure to respond to God. To speak of sin in legal terms is to miss the important aspect of sin as a religious, relational reality which expresses our refusal to respond appropriately to God’s love and mercy. Sin, simply put, is refusing to live out the gift of divine love” (Reason Informed by Faith, 92).

How, then, can I return to communion with God during this journey of Lent? This is an intensely personal question and requires your reflection and prayer (and, for some, the wise counsel of a spiritual director or spiritual companion). There is no “one size fits all” prayer practice.

A couple of weeks ago someone on Twitter made the claim that if you don’t pray the rosary every day, you aren’t “on the team.” Nonsense. I remember being told in high school how important it was to receive communion every day, and going to Mass every day during Lent became a strange kind of competition for kids in youth group. But here’s the thing. But prayer shouldn’t turn you into a jerk. I regret participating in the holiness olympics. That’s not what Lent is all about.

I’m a little older now, and hopefully more mature. I hear God inviting me to silence this Lent. More meditation, more mindfulness, more quiet. It will still take effort– saying “no” to this and that, turning off the devices that distract me, etc. Maybe for you the call is to connection–a faith sharing group, book club, or service project. Maybe it is a call to communion with God in the natural world– dedicated time for a hike, gardening, or sitting and listening to the birds. The point is that your Lenten journey can be as unique as you are, as you respond to God’s invitation to “return with your whole heart.”

Structures of Sin

Christian theology also has a lot to say about how we are formed within social worlds that constrain our moral imagination, socialize us to accept consumerism and a thirst for power, and prevent us from working together in love. In the first chapter of Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis spends a lot of time talking about “certain trends in our world that hinder the development of universal fraternity,” (10) including “myopic, extremist, resentful, and aggressive nationalism” (11), patterns of “a throwaway world” (19), “racism” (20), sexism (23), slavery and trafficking (24), war, terrorist attacks, racial and religious persecution (25), abuse of migrants and the worldwide tragedy of covid-19 (37, 32).

Today’s Psalm invites us to repeat “we have sinned.” Not only have I sinned, but we have sinned. I experience unearned privilege as a white person in a racist culture. I benefit from a tenure structure that exacerbates the marginalization of temporary adjunct workers. I participate in an economy of exclusion. I am complicit in the suffering of the vulnerable as I purchase fruit, buy clothing, let the faucet run. I am formed in a community that shapes me towards both good and evil. As the Catechism says, “structures of sin are the expression and effect of personal sins; they lead their victims to do evil in their turn” and “in an analogous sense, they constitute a social sin” (1869). There is so much injustice in our world that we lament. Our collective outcry for these structures of sin can be powerful ways of naming injustice and shaping our perceptions so that we can more fruitfully engage and transform social structures.

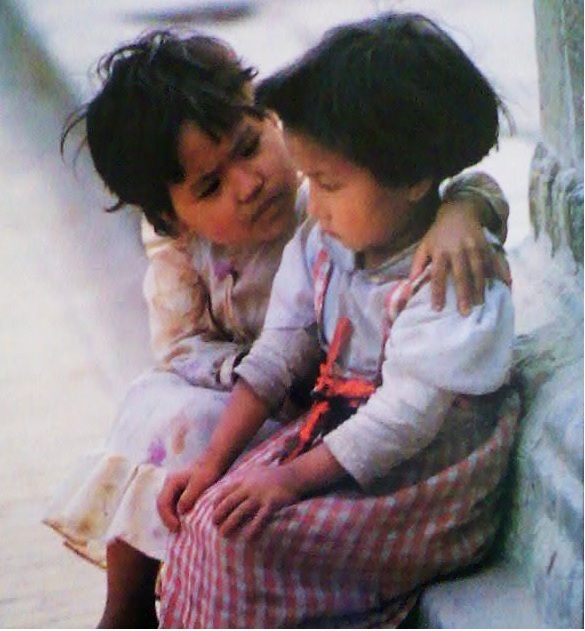

In the second chapter of Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis invites the reader to reflect on the parable of the Good Samaritan, reminding us that “indifference” to the suffering of the other is not the path to justice and love.

What Lenten practices would help us become aware of the structures of sin? Perhaps daily reading from an anti-racism reading list, starting a new mother support group, or joining outreach to the local homeless and hungry of your community.

Care for the Sinned-Against

Perspective matters. We all speak from somewhere. There is no “universal” human experience. This is an important caution for preachers as we talk about sin in the journey of Lent.

In any talk of sin, it is important for Christians to recognize the human dignity of the sinned-against, and to commit to “do no harm” in our liturgical and prayer practices this season. Survivors of clerical sexual abuse should never be asked to “repent” for the “church’s sin.” Partners who have suffered domestic violence in the home should not be told to forgive. Safety first. Justice second. Forgiveness later. If members of the congregation are struggling with eating disorders, a homily focusing on fasting may be detrimental to their healing and holistic wellbeing. Someone who just lost his job may not be able to give alms today. God understands.

Our journey towards Easter is an opportunity to return to God– our God who loves us unconditionally, our God who is gracious and merciful, slow to anger, rich in kindness. God is inviting us to communion with God and with one another. “If today you hear God’s voice, harden not your hearts.”

Trackbacks/Pingbacks