*Guest Post by Dr. Anna Floerke Scheid, Assistant Professor of Moral Theology at Duquesne University.

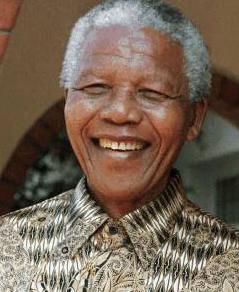

For many theologians, the death of Nelson Mandela – who has been a living symbol of peace, justice, and reconciliation – invites reflection on core theological concepts like the imago Dei, which Mandela wore with profound beauty and dignity.

For my part, I was first exposed to Nelson Mandela and to South African history during my undergraduate education, and since then I have developed a passion that far surpasses intellectual curiosity for the cultures and peoples that make up the nation of South Africa, and for its heartbreaking and hope-rendering history. In my development as a theologian I am indebted to the political and historical context of South Africa, so much so that my understanding of the most central theological concepts are all coloured in South African hues, or, if you like, steeped in Rooibos: Jesus Christ is Liberator; suffering and sin are apartheid (and thus inextricably linked – sin causes suffering); forgiveness is something we struggle toward because we want to be free from anger, hatred, and desolation; we want freedom from the desire for revenge, which leads to self and communal destruction; the fullness of reconciliation is the space where truth, mercy, peace, and justice converge. Reconciliation is God’s work – the fruit of salvation, divine grace.

Besides having the context of South African political history imbue my theological worldview, there are two specific theo-ethical commitments that Nelson Mandela and the struggle against apartheid have engendered in me.

First, Mandela convinced me of the veracity and viability of the just war tradition, and the importance of exploring its relevance for oppressed peoples. Mandela believed that those who are violently repressed by their government have a moral right to limited armed resistance. The Sharpeville Massacre in 1960, when apartheid police opened fire on unarmed protestors killing over 60, marked what Mandela himself saw as a turning point in the struggle against apartheid. Following the massacre, the African National Congress (ANC) met to consider how to respond. A great debate arose regarding whether or not to implement a program of armed resistance. Since its inception in 1912, the ANC had carried out only nonviolent forms of resistance. Some members, including then ANC president and Nobel laureate, Albert Luthuli, arguably a mentor of Mandela, contended that pacifism was a matter of absolute principle and that nonviolence was the only moral option for resistance. In his autobiography The Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela recounts how he believed

“that nonviolence was a tactic that should be abandoned when it no longer worked.” (275)

“Abandoned” here is too strong a word, I think, since Mandela himself argued just the opposite after the implementation of Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), the armed wing of the ANC. When describing this new phase of armed struggle, he said:

“Certainly the days of civil disobedience, of strikes, and mass demonstrations are not over and we will resort to them over and over again.”

Nevertheless, Mandela felt that a regime which gunned down its own civilians left the oppressed with little alternative other than to take up arms. While his post-apartheid commitments to forgiveness and reconciliation have led some to believe that Mandela was an absolute pacifist, the debate between those who advocated for armed resistance and those who opposed it illustrates that Luthuli was the ANC’s witness for pacifism, not Mandela.

Over the course of several years studying conflict and peacebuilding, I have been horrified and sickened by warfare. Many times I have considered rejecting entirely the notion of a just war, and instead adopting a position more akin to pacifism. It is, at least partially, Mandela’s insistence that a repressed people have a right to defend themselves, indeed to liberate themselves, that keeps me committed to the best ideals of the just war tradition; the notion that justice is a prerequisite for true peace, and that when peace and justice are gravely threatened, people may be called to die, and yes, even kill, to reconstitute true peace.

No one sums up this ideal better than Mandela himself. On trial for his life following the first attacks by Umkhonto, charged with sabotage and fomenting armed revolution, Mandela famously declared:

“I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons will live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But…if it needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

Second, Mandela has convinced me of the necessity of pursing post-conflict reconciliation, and of integrating this idea into the just war tradition. It is well known that Mandela emerged from his twenty-seven year imprisonment on Robben Island not to cry for revenge or retaliation, but rather to encourage South Africans to build a just peace that would include the reconciliation of the national community. Given that apartheid constituted the absolute antithesis of reconciliation – recall that the word “apartheid” means “apartness” – the call for reconciliation from Mandela was certainly extraordinary.

But to me, what is even more remarkable than Mandela’s role in initiating the Truth and Reconciliation Commission after the fall of apartheid, is that he, like many oppressed South Africans, viewed interracial reconciliation as a goal, even during apartheid’s brutal repression. Throughout the movement against apartheid, South Africans referred to the goal of post-revolutionary reconciliation as “the struggle within the struggle.”*

In this way, Mandela and the people of South Africa point to the of the importance of engaging in armed conflict only with a heart open toward future reconciliation. This kind of “right intention” in armed conflict – an intention to reconcile – ought to be a guiding principle for how warfare or armed resistance is conceived and conducted.

In closing his autobiography in 1994, Nelson Mandela wrote:

“I have walked that long road to freedom. I have tried not to falter; I have made missteps along the way. But I have discovered that after climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb. I have taken a moment here to rest, to steal a view of the glorious vista that surrounds me, to look back on the distance I have come. But I can rest only a moment for with freedom come responsibilities, and I dare not linger, for my long walk is not yet ended.”(626)

For nearly twenty more years, Nelson Mandela walked the road. Madiba, it is finished. You have climbed your last hill. Rest. The work of building peace, justice, and freedom is ours now. Thank you for helping to pave the long road.

____________________________________

* John W. de Gruchy, “The Struggle for Justice and the Ministry of Reconciliation” in Journal of Theology for Southern Africa, (no. 62, 1988, 43-52): 47.