This is a guest post written by Christopher McMahon.

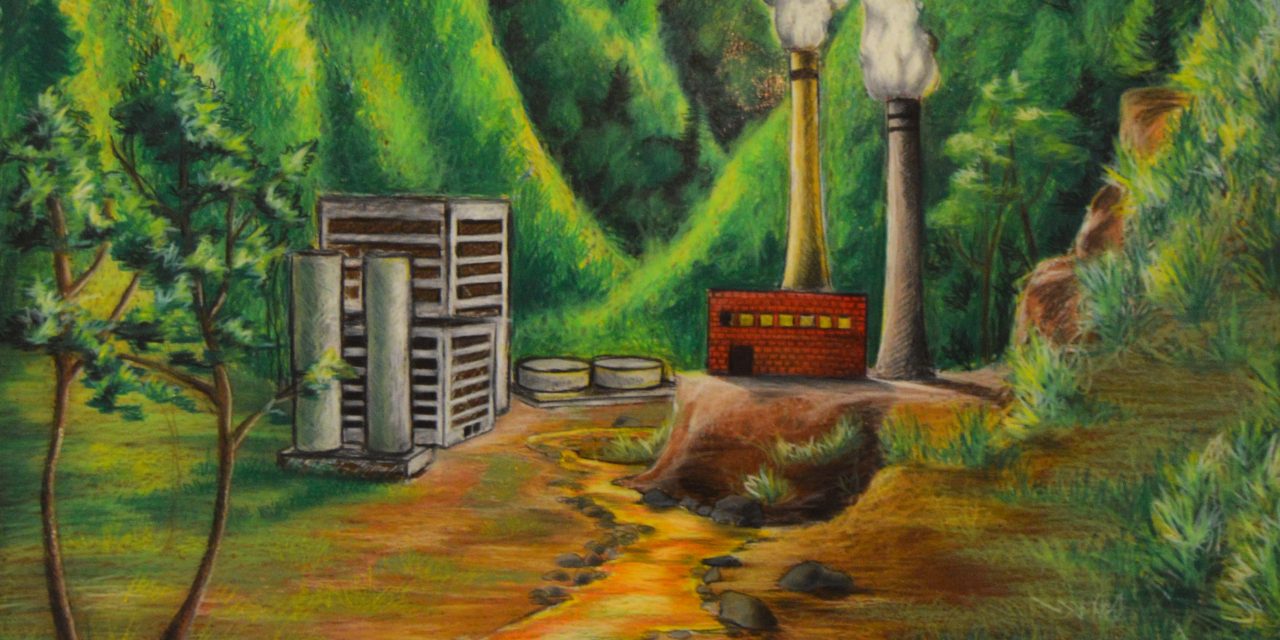

Cover art is by Rachel Wheeler

J.D. Vance’s poignant and provocative memoir, Hillbilly Elegy, recently examined the subtleties and frustrations of the Appalachian region in a manner many “city folk” found particularly illuminating and challenging. On October 21, 2016, approximately one hundred academics (students, staff, and faculty)—many of them “hillbillies” from the region known as Northern Appalachia—gathered at Saint Vincent College for an interdisciplinary conference on Laudato Si’ and its relevance for understanding and addressing the unique range of issues confronting the environmental, economic, and social issues confronting the region. The Journal of Moral Theology, in a special supplemental issue, has collected eleven of the papers presented at the conference and made them available to the general public. These essays not only provide powerful theological reflections on environmental ethics and theology; they also provide important insights into the history of region and efforts, particularly of Catholic groups and individuals, to prophetically challenge the status quo. One of the most remarkable features of these essays is that most of the authors have deep roots in the region, and this experience gives the essays a power and a vividness not always associated with conference papers.

The renowned eco-theologian, Anne Clifford, a native of Northern Appalachia (Uniontown, PA), provided the opening plenary address for the conference and now the lead essay in the collection. As with so many of the contributors to this volume, she evinces a deep personal experience of the region, a broad understanding of local history, responsible scientific insight, and sound theological principles. Her personal experience and commitment to environmental justice in the region anchors the volume and forms an inclusio with another native of the region, Jessica Wrobleski of Wheeling Jesuit University and the Catholic Committee of Appalachia, who provides the final essay in the volume, a poignant and hopeful reflection on the recent People’s Pastoral.

In the initial grouping of essays, Luke Briola provides the collection with a systematic foundation through his appeal to Bernard Lonergan’s account of conversion and its transformative impact in historical process, mediated in particular through the celebration of the Eucharist focused on local pastoral centers in the region. Derek Hostetter complements Briola’s presentation with his use of Chauvet’s sacramental theology to propose a synthesis of Laudato Si’ in what he calls an “integral Eucharist” where the story of Eucharistic bread production (and the role of agribusiness therein) fosters the kinds of questions within the church. Rob Ryan employs Pope John Paul II’s “theology of the body” to link Francis’s ecological vision and highlight the importance of embodied “encounter” in ecology.

William Collinge anchors a next group of essays that focus on the history of the region and the struggle to prophetically address the social and environmental crises of the past several decades. For his part, Collinge follows the history of the Catholic Worker farm in West Hamlin, WV, what he calls “an experiment” in developing an intentional Christian community to challenge the dominant culture of environmental degradation and to address the problem of surface mining. The history of that community, Collinge suggests, provides important lessons—both positive and negative—for environmental activists. Jinny Turman covers some of the same ground as Collinge, but with a focus on the manner in which the WV Catholic Workers’ “mounting concern for dialogue, civic participation, and land-based independence helped to shape the emergence of green civic republican rhetorical strategies in the county’s debates about strip mining” (97). Tim Kelly moves in a similar direction as he examines three critical environmental episodes in the region: the development of the subsistence homestead community of Norvelt, PA, in the 1930s and 1940s, the Donora smog disaster of 1948, and the emergence of the modern environmental movement of the 1960s. Through his examination of these episodes, Kelly seeks to understand the historical emergence of the modern environmental movement of the 1960s and a corresponding Catholic environmental ethos that emerged by the end of the century as it “percolated at the grassroots for some time before getting official recognition.” Nancy Rourke draws on her family history to chronicle the struggle to resist fracking on family farms in upstate New York as well as the role Reformed theology (the theology embraced by most farmers in that region) plays in complementing the insights of Catholic social teaching on the environment.

The interdisciplinary collection of essays concludes quite intentionally with two essays focusing on communication and literature. John H. Prellwitz provides a communicative-rhetorical analysis of Laudato Si’ that integrates theories from philosophers (e.g., Levinas) with theological insights (derived from, e.g., Zizioulas and Ratzinger) and likens the journey to ecological conversion as that of mystagogy. David von Schlichten provides a reading of Anne Pankake’s Strange as This Weather Has Been in light of contemporary eco-feminist theology and Laudato Si’. This literary analysis provides the inclusion with Clifford’s opening essay and the recurring theme of the volume: the importance of an integrated and embodied discipleship in the face of the environmental crisis.

The conference and the collection of essays it inspired should stand as a call for more consistent efforts for Catholic colleges and universities to sponsor similar projects and begin to devise curriculum and research that will foster the integral ecology so desperately needed to heal and transform the complexity of our contemporary crisis. Although the conference included presentations on local environmental studies and projects from the natural sciences, these papers/presentations were not suitable for the JMT volume. This omission represents one of the shortcomings of the collection of essays, but the emergence of an integral ecology requires the engagement of a full range of disciplines. Such an engagement is uniquely suited to the function and purpose of Catholic institutions of higher learning.