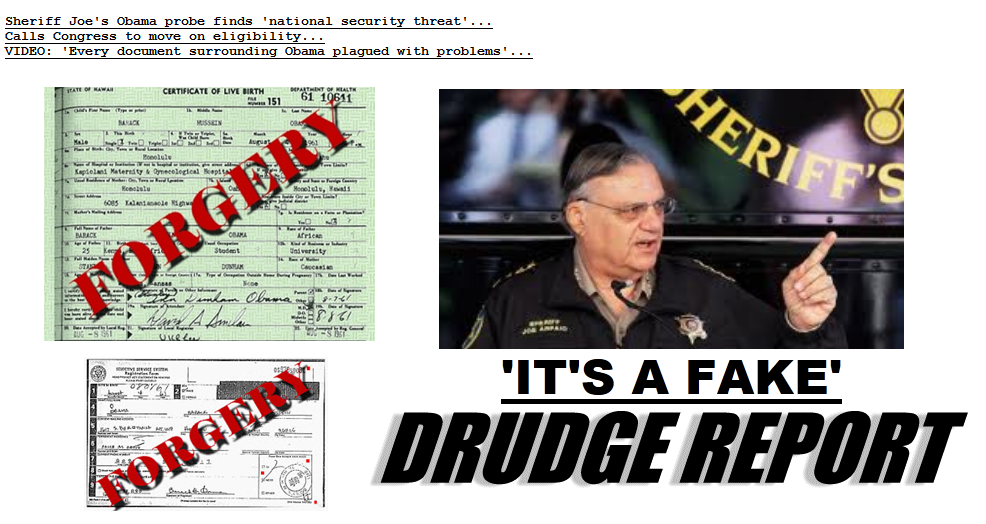

One of the most intriguing stories to emerge in the aftermath of the presidential election earlier this month concerns the increasing prevalence of “fake news.” A growing number of people access the news through social media, in particular through links to articles posted on Facebook and Twitter. Taking advantage of this shift, a number of web sites have popped up that generate news stories that are completely or in part fabricated, and amid the chaos of social media, these fake stories are posted and shared right alongside evidence-based journalism. There is evidence that during the election campaign, people were sharing and reading fake news at a rate equal to, if not greater than, real news, potentially shaping the outcome of the election. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg at first denied that fake news shared on his platform had any influence on the election, but more recently he has detailed a plan to help combat the phenomenon.

What accounts for the prevalence of fake news? Why are people seemingly unable to distinguish fabrications and exaggerations from evidence-based reporting? For one, justifiably or not, skepticism of the so-called “mainstream media” is sky high. This wariness toward the media is linked to a much broader skepticism toward experts that I believe is characteristic of contemporary life. Politically-motivated fake news is also just one variation of the now familiar phenomenon of “clickbait,” sensationalized articles or advertisements designed to lure you into following the link to generate more advertising revenues. Clearly the marketing structure of social media bears some of the blame.

All of these factors deserve to be explored in more detail, but in this post I am more interested in looking at how Christians ought to navigate social media, knowing that much of the information being shared there is “fake.” I think it is vital for us to revisit the notion of the “intellectual virtues,” those skills or habits of mind that help us discover and discern truth. Indeed, after months of observing and participating in social media leading up to the election, it seems undeniable to me that a person’s habits of mind shape how they respond to the information and disinformation presented to them. Hyper-partisans of both the left and the right will excoriate the mainstream media as biased and untrustworthy, and then credulously read and share the most outrageous conspiracies. Those who take the independent stance of giving a skeptical eye to any and all media often turn out to be very “low information” citizens. The point here, however, is not to look down on anybody, since if the election has revealed anything, it is that most of us to one degree or another have been lacking in intellectual virtue: the inability of the “cultured elites” to grasp the concerns of white, rural and small town America and therefore to foresee Trump’s victory; the creation, by Clinton and Trump supporters alike, of “two bubbles of unrealism.” The proliferation of “fake news” is only part of this much broader problem.

One of the first to consider the intellectual virtues was the Greek philosopher Aristotle, in Book VI of his Nichomachean Ethics (St. Thomas Aquinas considers them more briefly in his Summa Theologiae, I-II q. 57). Aristotle distinguishes the intellectual virtues, which are the skills and habits conducive to knowing the truth, from the moral virtues, the skills and habits conducive to doing the good. This distinction is important because it means that possessing the intellectual virtues does not make one a better person from a moral perspective; there is such a thing as an evil genius, after all. The intellectual virtues are skills that can be put to good or bad use. The exception here is the virtue of prudence (or practical wisdom), the skill of discerning what to do in a particular situation, which Aristotle considers an intellectual virtue despite its orientation toward doing. Here I want to briefly look at the other three more purely intellectual virtues described by Aristotle and how they might be relevant in responding to the phenomenon of fake news.

Knowledge: What Aristotle means by the virtue of knowledge is fairly-straightforward—a familiarity with the findings of the various sciences or fields of inquiry. It may seem strange to think of this as a virtue, but for Aristotle knowledge is not simply the accumulation of facts in the mind. Rather, “it is when a man [sic] believes in a certain way and the principles are known to him that he has knowledge, since if they are not better known to him than the conclusion, he will have his knowledge only incidentally.” In other words, to possess the virtue of knowledge, one must not only accumulate facts, but also be competent in the appropriate inductive and deductive methods used to discover new facts and to link facts together. Of course, it is expecting too much for people to have specialized knowledge in all of the fields that might be relevant when reading the news, but it is not too much to expect Christians to strive toward a basic competence in areas like science, politics, and the law to better evaluate the claims made in news stories.

Comprehension (or Reason): What Aristotle means here is knowledge of the “first principles” of reasoning, what we might consider the principles of logic or of rational inquiry. In a sense we all possess some knowledge of these principles since they are necessary for any kind of reasoning, and therefore the name of this virtue is sometimes translated as “intuition.” However, Aristotle is also clear that we can also mature or develop in our knowledge of these principles, which suggests that we come to a more explicit grasp of the principles of sound reasoning, even apart from any particular knowledge we obtain. It is easy to see how greater familiarity and facility with the principles of logic are essential for navigating the news on social media.

Wisdom: By wisdom, Aristotle means knowledge of the “highest” things, those things most worthy of our contemplation. Aristotle clearly means philosophical reflection, but from a Christian perspective we should also consider theological or spiritual reflection. Of the three intellectual virtues this one might seem the least relevant for engaging with “fake news,” which certainly deal with “lower” things. However, I have always been fascinated by Aquinas’s treatment of the vice of “curiosity,” which is in part the inordinate desire to know less profitable things that distract one from higher, more obligatory things. Surely part of the attraction of fake news is this inordinate desire to “know,” even to the point of accepting such “knowledge” uncritically, much like people have always done with gossip.

Aristotle’s intellectual virtues are certainly helpful, but I think they can also be supplemented by the more recent work of a group of philosophers known as the virtue epistemologists. These philosophers, like Ernest Sosa and Linda Zagzebski, have recovered the notion of intellectual virtues to address contemporary epistemological problems about what counts as justified knowing. Although I am not concerned with those questions here, I still believe their account of intellectual virtue is of use to Christians. For example, the philosopher James Montmarquet has argued that Aristotle’s distinction between the intellectual and the moral virtues unfortunately downplays the moral quality of seeking truth. He therefore develops a list of virtues that are in a way both intellectual and moral, which supplements Aristotle’s list.

Epistemic Conscientiousness: For Montmarquet, this is the central intellectual virtue, the desire for truth. We should always avoid intellectual laziness or a willingness to be deceived. All the other intellectual virtues described by Montmarquet specify this one.

Virtues of Impartiality: Montmarquet argues that an intellectually virtuous person demonstrates the virtues of impartiality. This includes being willing to consider others’ ideas, even when they are very different from one’s own. I think much of the conversation about fake news and social media bubbles has focused on this set of virtues, since there is a crying need for people to be exposed to and to reasonably consider others’ ideas and perspectives. Montmarquet also considers here the virtue of recognizing one’s own fallibility, the fact that one could be wrong.

Virtues of Intellectual Sobriety: Here Montmarquet refers to our common tendency to leap to conclusions that confirm our passionately-held beliefs without going through the proper exercises to confirm if those conclusions are true or not. The virtues in this category help us resist these temptations.

Virtues of Intellectual Courage: In this category Montmarquet considers those virtues needed when the pursuit of truth becomes difficult. For example, sometimes the pursuit of truth leads one to conclusions that cut against what is popular or what is considered common knowledge. Sometimes intellectual work itself is difficult and it is tempting to take short cuts rather than to investigate a question with the thoroughness that it requires.

Montmarquet’s list of intellectual virtues provide a set of mental habits that Christians can strive to achieve and embody as they engage with the flood of information, both true and false, and with other people on social media.

The problem of “fake news” is symptomatic of larger, underlying issues in our society, and it will require a great deal of time to properly analyze and respond to these issues. In the meantime, however, as Christians it is still within our power to respond to this problem of fake news with a sense of personal responsibility. I believe that a renewed effort to cultivate the intellectual virtues, as conceived by both the ancients and the moderns, is an important part of that response.

Excellent article Matthew, thanks for sharing it.

It seems that to the degree we develop Montmarquet’s list of intellectual virtues within ourselves, we may ironically find our circle of influence shrinking.

Would your very intelligent, thoughtful and informed article go viral in social media? It should, but won’t, because you are speaking at a level most can’t reach, or can’t be bothered to reach. The quality of your thinking and writing condemns you to be going not viral but kind of nowhere, in front of a very small audience.

The point here is that quality of thinking is not enough if one wishes to be an effective citizen. For the value of quality thinking to be multiplied, for it to have real power to do good, we must also learn how to present such thinking in a package that others can access.

To give myself an ulcer, I will suggest we might learn from Trump here. His thinking is appalling indeed. But it seems we must admit Trump has mastered the art of taking the stage, keeping the focus, and packaging his appalling thinking in to a simple and persuasive form that can be widely accessed.

As for fake news, I believe it has exploded because the corporate media no longer covers the news. They’ve changed their beat. They cover drama now.

To give myself a headache too, I must also admit that Trump seems to understand this reality better than anyone currently on the public stage. As a businessman from New York City (capital of global media) Trump gets that the real bias in corporate media is not for left or right, but for profits. You boost profits by building audience, and you build audience with drama.

Trump dutifully supplied the needed drama, and corporate media completed the transaction by providing Trump with round the clock coverage and billions of dollars worth of free advertising. By the way, this same poisonous partnership exists between corporate media and terrorists.

I don’t have time to be cynical about fake news, as it seems there are so many bigger fish to fry.

I like this post a lot. I have been pretty perplexed at the level of suspicion towards mainstream media, which Trump has alleged has never seemed so biased. I consume quite a bit of mainstream media (NPR, NYTimes, The Economist) and I consider myself pretty moderate politically and I am just not seeing the bias. Sure, I get that newspapers overwhelmingly endorse liberal candidates, but as far as the journalism goes, I usually don’t feel like I am reading biased pieces, nor that mainstream media is manipulating me. I am curious what you think, Matt. Is mainstream media biased, or are these accusations and suspicions ultimately grounded in the fact that readers are not well trained in the intellectual/moral virtues, particularly Montmarquet’s list?

The other thing I thought about when reading this post is if and how we are helping to foster these intellectual virtues here at the blog. I think we do but I might also keep referring back to Montmarquet’s list as a sort of check on my own writing over the next, say, four years.

Hi Beth. I like this post a lot too. Much to think about here.

Although every human being is infected with bias, I agree the mainstream media makes a good faith effort to set political bias aside. In any case, there are SO MANY different news sources now that any political bias that does exist is balanced out by all the other outlets. Maybe political bias was an issue back in the sixties when there were only three national TV networks, but those days are gone.

Again, the heart of Trump’s evil genius is that he understands that the real media bias today is for profits. Even NPR is now forced to focus on drama to boost audience and ad revenues. Few of the other media outlets need to be forced in to the bias for profits, because they are openly and forthrightly big corporations whose entire reason for existence is to deliver value to shareholders. The bias for profits is not just a preference, but a legal obligation in any publicly owned company.

Here’s a concrete example of what I’m referring to.

The most important topics of today are nuclear weapons and climate change, as both these factors threaten to bring civilization itself crashing to it’s knees. Neither of these existential threats received hardly any attention from the media during a year long presidential election. Instead, every time Trump said or did something dramatic he got a week of round the clock coverage. That’s the distorting bias for profits at work. The business model formula is…

Drama => Audience => Ad Sales => Profits

Trump won because he understands this reality better than any of his competitors, due to the fact that he’s been laser focused on profits his entire life, and lives in the corporate media capital of the world, New York City.

While Trump is clear minded about the reality of modern media, the rest of us are still stumbling around in the happy delusion that mainstream media is about providing a public information service. This is a fantasy story that the media tells itself about itself, and because they own the conversation, they’ve been able to successfully sell the fantasy to us too.

The big challenge that we face is that pretty much every major media outlet has to have a profound bias for profits, or they will soon go out of business in today’s hyper-competitive media marketplace.