Earlier this month, the Catholic Theological Society of America, the self-described “principal association of Catholic theologians in North America,” held its annual convention in Indianapolis, IN. I had the opportunity to attend and, as I usually do, found it intellectually stimulating and enriching. The Saturday morning plenary session, especially, stuck with me, in large part because I continue to see its practical relevance confirmed on an almost daily basis.

David DeCosse of the University of Santa Clara gave that Saturday morning address, and he framed it as a theologian’s reflection on what the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops might want to consider as it plans for the 2020 update of its Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship.

That document is (re)issued every four years in conjunction with the presidential election. It is designed to offer insights from the Catholic tradition that can guide Catholics as they discern how to vote in their local, state, and federal elections. The thrust of the document in any given election cycle is usually pretty similar to its predecessors, but there are always additions and adjustments that are meant to speak more directly to the matters of the day. DeCosse used his address to explain why the 2020 election might rightly prompt a more substantive review than normal.

Overall, I found myself very sympathetic to DeCosse’s points, perhaps in part because I know that both he and I have a deep commitment to the theology of conscience that springs from the Second Vatican Council’s Gaudium et Spes (no. 16), and this personalist vision informed his comments. More importantly, though, I saw a lot of prudence in what he was saying.

Perhaps the best illustration was his suggestion, almost as an aside, that the bishops might want to think about other ways to disseminate the content of Forming Consciences in our tech-saturated world. It’s hard to disagree that in today’s social media landscape, A 40-page document might not have the same power to command the narrative that it once had. Now, a CMT dot com blog post, on the other hand…

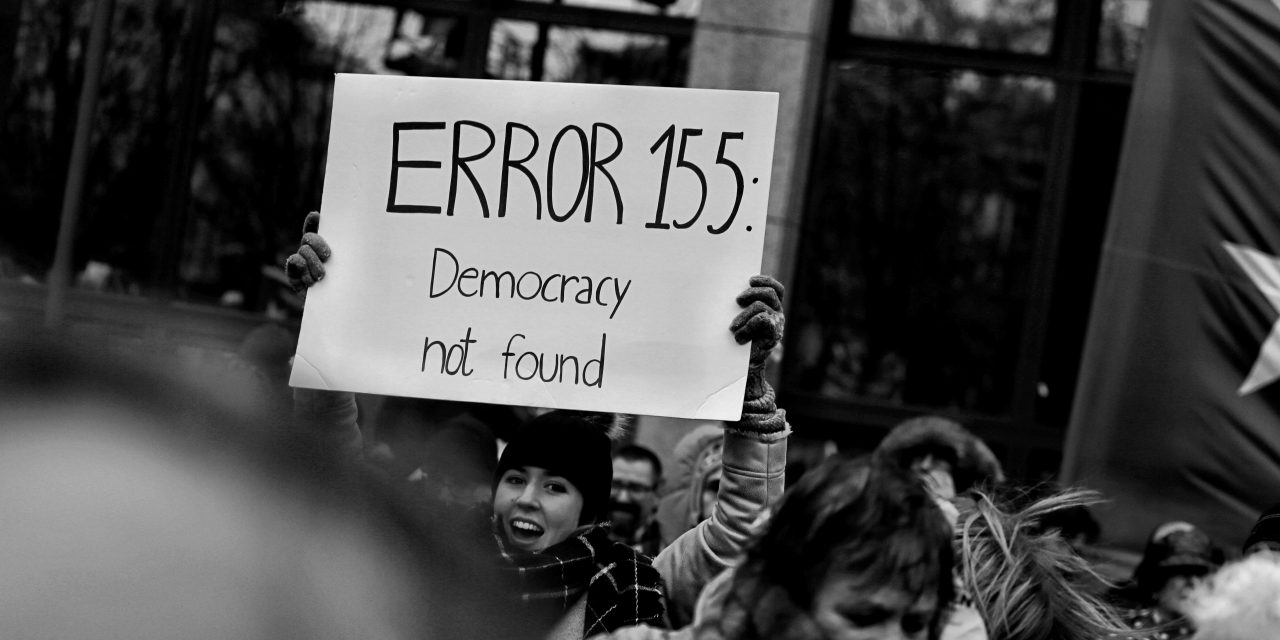

Nevertheless, the major point I really took away was DeCosse’s assertion that the bishops ought to use the document (in whatever form it takes) to call Catholics’ attention to the importance of supporting our democracy itself. In essence, DeCosse was reading the signs of the times and concluding that for the 2020 election, isolated issues shouldn’t be at the fore as much as meta-level questions about the survival of democratic governance.

I’m convinced DeCosse is right. I’m also worried the solution will come two years too late.

There is ample reason to believe that our democracy is facing something of a crisis. For instance, thanks to the president’s cavalier attitude toward the truth, lies have become so commonplace in our public discourse that the idea of “alternative facts” has transformed from some kind 1984 allusion to standard operating procedure. These lies have already been used for dastardly political goals, including as a “justification” for the horrendous practice of separating children from their parents at the border. That lies would be deployed in this way to cover for the kinds of divisive policies that would once have been unthinkable in our democratic society shows their damaging potential, but just as significantly, the effects of lies on the brain suggest they pose an even more fundamental threat to our participatory democracy.

Meanwhile, insane amounts of money lurk behind legislative priorities, much of it legally funneled to candidates and their campaigns through “Super PACs” and other vehicles (see the informative and accessible Stephen Colbert crash course for more details). As a result, everyday citizens are left to wonder whether anything can get done in the public interest. No less invested an observer than former President Jimmy Carter recently opined,

Now [the United States is] just an oligarchy, with unlimited political bribery being the essence of getting the nominations for president or to elect the president. And the same thing applies to governors and U.S. senators and congress members. So now we’ve just seen a complete subversion of our political system as a payoff to major contributors, who want and expect and sometimes get favors for themselves after the elections over.

Is it any wonder that a majority of Americans report that they distrust democratic institutions like the presidency, Congress, the media, and both political parties? How can one expect government of the people, by the people, and for the people to function let alone thrive in an environment of such cynicism?

For Americans in general, this state of affairs should be troubling. For American Catholics in particular, this should be untenable.

The Catholic Church has long insisted, on the basis of its Trinitarian theological anthropology, that the state serves a necessary function in God’s plan for full human flourishing. (For a succinct explanation of the links between theological anthropology and the Catholic vision of the state, see Kenneth Himes’s Christianity and the Political Order, pp. 196–199.) The state is, simply put, essential for the realization of the common good.

Naturally, the Catholic vision for the state does not mean that the Roman Catholic Church gives uncritical support to every (or really any) particular nation state. This teaching is about the state and its responsibilities in the abstract ideal; it is not a comment on any particular government. There are, however, degrees of participation in this ideal, and citizens’ abilities to shape the work of their own state is a major determinant in how faithfully a given form of government aligns with the Catholic vision for the state.

This concern is most evident in what the USCCB’s “Seven Themes of Catholic Social Teaching” refers to as the “Call to Family, Community, and Participation.” According to this strand of Catholic social thought, participation in the community’s efforts to discern and then to seek the common good is both a right and responsibility of each human person.

Hence, a functioning form of democratic government is a valuable good according the Church’s social teaching, and when that functioning is called into question (as it is increasingly in the United States today), it would behoove Catholics—both individually and collectively—to pay attention and do something about it.

These observations all indicate why I found DeCosse’s proposal for the bishops so appealing. His suggestion gets to the heart of the Catholic vision for the state at a time when this kind of analysis is especially important. It also makes a lot of pragmatic sense, for as DeCosse pointed out in is address, the bishops cannot address any of their typical political priorities (think outlawing abortion, humanely responding to immigration, combating poverty, achieving universal access to health care, etc.) without the structures of our government in place and working well.

What then are we to do?

This is where DeCosse’s plenary has been on my mind in the last few days. What it would really take is a concerted effort to reform the very structures of our democratic society so that we can reclaim confidence in our system of governance and maybe even get some real change accomplished.

This is the message that groups with power and authority need to convey, and so it would be good if the bishops emphasized this message. It is also the message that concerned citizens need to bring to their elected representatives, for our concerns become their concerns.

There is some indication that this is already happening, at least on one side of the aisle. The Democratic Party has just launched “A Better Deal for Our Democracy” as part of their 2018 midterms push, which outlines the party’s plans to address corruption, beef up ethics standards, and reform campaign finance law. The move was apparently spurred by cynical critics who doubted the Democrats’ working-class economic agenda could get any traction in a political system shaped by unlimited corporate expenditures and anonymous donors.

Unsurprisingly, the plan is big on rhetoric and thin on detail, but in the aftermath of DeCosse’s address, I was at least heartened by the fact that a major political party is speaking about the unglamorous, yet eminently necessary issue of structural governance.

Of course, this is only one political party, and Catholics rightly note that they have no happy home in one political party alone. It would be far better, then, for Catholics to pressure both political parties to commit to this serious issue, so that there might be a better chance of change in the offing. After all, this is really is an issue that transcends both parties.

If the USCCB were to promote this as a major concern, it might considerably help the effort to get all parties on board, but we’d still only be talking about a document for the 2020 election. There is a significant election in less than five months, and so perhaps we can find ways to use the lead-up to that contest to push for some kind of bipartisan acknowledgment of the need for reform. And, maybe, Catholics can agree to focus on the health of our democracy itself as they go about the discernment in conscience that will inform their participation in the 2018 election.

I’d say faithful citizenship demands no less.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks