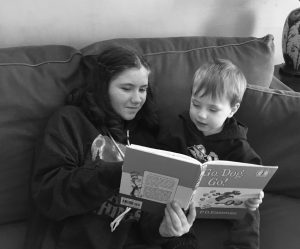

Photo property of the author.

Last night, after a quick card game with my two sons (ages 9 and 7), we settled in for what is my favorite time of the whole day: when I read aloud to them. Although I also enjoy reading picture books to my younger boys (ages 4 and 2), it is a special gift to be able to share with these older sons more difficult and rewarding texts, such as The Lord of the Rings, Swallows and Amazons, and the Harry Potter series, among others. Admittedly, my 9 year old is already an advanced reader and generally has a better attention span than my younger son. Nonetheless, I was offended when the younger son caught sight of an iPad and suggested that he use an educational reading app while I was reading aloud to them.

He had numerous reasons for this. He argued it was better for him to practice his own reading than to listen to me reading. He noted that he’d already gone up one level today and might make it up another level. He wanted to have the most points in the class. He stated that he was only a few points away from being able to buy another piece of his robot. He said it was fun to watch the monkey doing the orange justice dance. In a matter of minutes, my older son was sitting next to him, helping him answer the comprehension questions that would win him the needed points…and ignoring my reading of The Vanderbeekers.

I should be sympathetic; after all, I’ve had my moments (notably during the philological sections of Tolkien’s LOTR appendix) of checking my email on my phone during our reading time. But this incident was simply one more strike against educational apps in my experience, both as a parent and as an educator of college students.

Nine years ago, when my oldest daughter started kindergarten (and before I had an iPhone), I’d never heard of an educational app. Now, however, it seems every week brings another suggestion of a spelling app, math app, reading app, art app, or science app, not to mention requests to complete homework online or do an online practice test using the district’s website. It seems assumed that each of my three elementary-aged children must have their own device, or at least, access to it.

The advantages to these apps seem apparent. They can be great for learning math facts, correct spellings, and vocabulary words, with repetition to target earlier mistakes. Given that we know children spend an enormous amount of time on screens, this seems a better use than regular zombie-killing games. Not to mention that this is the world we live in now; reading is often done online, and they need to know how to do it. Reading apps do a great job testing comprehension, unlike when a child reads on his own for pleasure. And, of course…since many tests are now given online, being able to do math and reading on an app is valuable preparation for success in standardized testing.

Moreover, from a teacher’s perspective, these apps can provide immediate, organized feedback indicating where a class or individual student is struggling, so that the instructor can target that weakness. We can see how teachers and administrators find these apps valuable. Parents can feel caught in the middle, as I did when my oldest son burst into tears after I refused to pay $9 a month for a recommended reading app. In the first month free trial, his point total was the highest in the class, and now he knew he’d lose this distinction because I wouldn’t pay monthly for the app. Our pediatrician reminds me at every visit that I should limit my children’s screen time, but the school’s list of recommended apps keep growing.

Like teachers, we parents want our children to learn their math facts, get their spelling right, know geography, be proud of their artwork that’s posted online, and learn how to answer reading comprehension questions. Moreover, we don’t want them to feel isolated or left behind in their classroom where other students take advantage of these apps. And isn’t it better for them to do an educational app than to watch Dinotrux on Netflix?

On the other hand, both as a parent and as an educator of university students, I see several disadvantages to these apps. First, and most significantly, educational apps prioritize the extrinsic rewards of learning, rather than the intrinsic rewards.

Those of us who love to read know the great joy and satisfaction that comes with reading an excellent book. There is an internal delight as we are pulled beyond ourselves to a different world. This is an intrinsic reward, part of the very act of reading itself. While reading apps may not squash these intrinsic rewards altogether, they nonetheless emphasize answering questions, winning points, building a robot, competing with classmates. These are all extrinsic rewards that work well for motivating students to master the basic skills of reading, but do little to inspire a love for reading that will last into their days as young adults in college and beyond.

The need to answer the questions correctly in these apps means a focus on reading in order to respond to something externally imposed on the reader because it is judged to be of importance. Reading on one’s own inspires internal questions, more creative and often speculative in nature. Should the hobbits trust the cloaked figure of Strider at the Inn in Bree? Is it Saruman or Gandalf that Aragorn, Gimli, and Legolas encounter on March 1st? The questions may later be resolved in the reading, or they may remain fodder for days of continued reflection; this wins no extrinsic reward, yet becomes its own reward simply as an enjoyable subject of thinking and reasoned argument.

Classroom education has always had a competitive aspect, from peeking at a friend’s math test score to comparing report cards to winning school awards for various categories. Nor is this something that must be avoided at all costs; indeed competition has some benefits. The competition provided by certain apps, however, is misleading and at times problematic, reflecting the willingness of parents for children to use these apps more than the abilities of the children themselves. One art app, for example, provides points to children for every piece of artwork they upload.

My oldest daughter has always loved to sketch, and at times she spends up to three hours drawing. Other than occasional parental affirmation for her work at the end, she doesn’t receive any extrinsic reward for these hours spent drawing. The art app, however, provides the class count for uploaded artwork, and, at the end of the school year, one student is given an award for it. Note that it’s not for the quality of the artwork or improvement of the artist; the award is simply for the most pieces of artwork uploaded to the app. I had my moments of feeling a pang of guilt at the end-of-the-year awards assembly, knowing my daughter could easily have won this award if I’d been willing to upload every sketch she did. But, on the other hand, I don’t want her to sketch for extrinsic rewards, such as recognition in front of the school. I want her to draw because she loves and enjoys drawing; this will keep her motivated more than any award.

So also with my son who cried when I refused to pay monthly for a reading app. His reading level is far above grade level, and I know he could easily establish himself as first in the class with points on the app. But to me, these extrinsic rewards are not only unnecessary, but also problematic. I want him to read because he loves reading, not because he wants to beat his classmates and to be publicly recognized with an award for his app reading.

Another intrinsic reward of education is a sense of self-mastery and impulse-control. Making flash cards and sticking to a study schedule brings an intrinsic sense of accomplishment; this is something the student did on her own. Picking up a book and reading it throughout the week involves a feeling of achievement at the end (even if it’s not recorded in a reading log!). Studies have shown that use of screens fosters the opposite – not only in children, but also in adults. We adults find ourselves slavishly responding to our notifications even at bad times, and children’s decisions also become less conscious and simply responsive to the app in front of them.

Finally, one last intrinsic reward of education is the understanding of it being a team project of human beings. Education relies on human interaction, from the help of parents with tricky math problems to the motivation provided by a good teacher to the assistance of a classmate. Good education fosters a sense of unity and community, and even of service. We are joining in together on a conversation started long ago, doing our best to further that conversation. Thus my son’s reading app is not an adequate replacement for an hour and a half of listening to my reading; the intrinsic reward of bonding with a parent and sharing in a story fosters that love of reading in a way that earning comprehension points simply doesn’t.

As a university educator in the liberal arts, it’s frightening to think of the long-term effects of these educational apps. I already see in my students the preliminary results of a focus on extrinsic rewards, most especially in their obsession with their grades, but also in their tendency to read (or perhaps, scan read) only with the purpose of answering comprehension questions, and only when required. The tendency to rush reading often results in incorrect answers; for example, they fail to notice that an author was presenting a viewpoint to be later refuted and instead cite that as the answer.

Moreover, they readily admit the difficulty they experience with impulse control around their phones, and they realize that they lack focus/concentration for extended, quality work time. With the rise of internet and computers becoming standard in the classroom, education has not contributed to their self-mastery and control but has largely joined these other influences.

Educational apps no doubt may bring with them short-term gains, but with these we must consider the possibility of unintended long-term consequences. Most especially we should expect a further diminishment in the appreciation for the intrinsic rewards of education – a loss of the love of learning for the sake of learning.