Our lives are permeated with desire. From the moment we are born, our every action seems to be a response to some desire. Any action attributable to us as agents is born of desire, initiated by the movement of our will toward some end perceived as good. Anything we do intentionally, we do in order to obtain some desired end. This dynamic of desire and action appears to attend every conscious moment of our lives. Even in those times when we stop what we’re doing or decide to “do nothing,” we do so with some desired aim in mind, even if only to better determine what we do or should desire. Our desires haunt us even as we sleep, as our minds attempt to configure our countless perceptions in light of the continuous undercurrent of our desires whose depth extends beyond our conscious awareness. In short, our life is a never-ending quest for what we desire. At the moment when we seem to possess one desired good, another takes its place. Those fleeting moments of satisfaction fade like whisps of smoke, leaving hydra-like in their absence even more desires than were there before. And so we run from desire to desire, ceaselessly laboring to reach a destination that recedes ever further further into the horizon. The recognition of this fundamental dynamic of human existence can itself offer no escape from it, though it can lead us to the sort of lament we hear from Qoheleth, that “all is vanity… a chasing after the wind” (Ecc 2:11).

So when in the concluding lines of this Sunday’s gospel reading, we hear Jesus saying “come to me, all you who labor and are burdened, and I will give you rest,” we can rightly think of the “labor” and the “burden” as something integral to our existence as we experience it. We are always “after something;” looking, seeking, pursuing. Presumably the people gathered around Jesus at this moment were following him and listening to him because they hoped to find in his words and deeds some good that might satisfy their desires. Recall Jesus’ first spoken words in the Gospel of John, addressed to two curious disciples of John the Baptist: “what are you looking for,” often translated as “what do you want?” It is a question addressed to all of us, in so far as we all come to Jesus always already engaged in the endless pursuits that define our lives. In today’s gospel, Jesus offers himself as the ultimate good in which we can find rest from this toil of ceaseless desire.

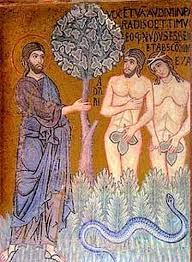

Genesis tells us that in creating the world, God labored for six days and then rested on the seventh. As many have pointed out over the centuries, this final day the creation story stands out not only because God performs no labor during it, but also because it does not conclude with the formula “evening came and morning followed.” The narrative merely continues with the Yahwist creation account, which does not specify discrete periods of time . The transition between these creation accounts can therefore imply that the Eden story takes place on the seventh day. Many Jewish and Christian theological interpreters have gone so far as to suggest that the seventh day has never in fact ended, but encompasses all of history even up to the present. According to this interpretation, all human history unfolds during the seventh day, against the backdrop of God’s Sabbath rest. The principal mark of this rest is God’s delight in what He has made, a delight in which human beings were meant to participate as they exercise dominion over creation. Humanity’s task was to “work and keep” the garden, the paradigmatic image of peaceful, unburdened activity. The “painful toil” that eventually comes to characterize human activity is not part of this original pattern of life, but is rather the result of humanity’s alienation from creation through sin. We have all been seeking the peace of Eden ever since.

God gives the Sabbath to his people as a way to remember and participate in this original rest, if only partially and temporarily. Psalm 95 makes clear that one of God’s main aims in leading the people into the promised land was to give them this rest, a rest that the people forfeit through faithlessness: “So I swore in my wrath, ‘they shall never enter My rest’” (95:11). Yet the author of Hebrews insists that “the promise of entering His rest still stands,” and that “there remains a Sabbath rest for the people of God; for anyone who enters God’s rest also rests from their works, just as God did from his” (Heb 4:1, 10). How then does Jesus’ invitation to rest relate to this promised “Sabbath rest”?

“Come to me,” says Jesus, “and I will give you rest.” What does this rest look like? Jesus offers us an unexpected image: a yoke. It is hard to imagine something more clearly associated with burdensome toil than the yoke one attaches to a beast of burden in order to plow fields. Yet Jesus offers it as the way to true rest: “take my yoke upon you and learn from me, for I am meek and humble of heart; and you will find rest for yourselves.” The task of those who bear this yoke is not to perform any labor for Jesus, but merely to learn from him, and specifically to learn how to make his heart their own. The person of Jesus Christ therefore is the rest we ultimately seek. In him alone do we see an image of humanity truly at rest in the world. It is thus only by conforming our own desires to his that may learn how to abandon the frenetic and fruitless toil of seeking out one temporary good after another. It is only by grafting ourselves into Christ, such that his relationship to the world becomes our own, that we come to enter into the true rest for which we were created and for which we still long.

The other image of rest Jesus offers us is that of childhood. “I give praise to you, Father,” Jesus exclaims, “for although you have hidden these things from the wise and learned you have revealed them to little ones.” Children know a form of rest that most adults come to renounce or forget. David speaks of this sort of rest in Psalm 131 when he says, “I have calmed and quieted myself, I am like a weaned child with its mother; like a weaned child I am content” (131:2). An infant in her mother’s lap can rest in a way we find all but impossible in adulthood. Why? Is it the child’s obliviousness to the world, and to all the many varied goods it contains? Or is it the child’s trust in her parent, which makes possible a simplicity of desire that affords her the sort of satisfaction and delight we find almost nowhere else? Jesus tells us that the secrets to true and lasting satisfaction are hidden to the wise and learned, but revealed to “little ones,” to those whose hearts are meek and humble, driven not by complex and lofty aspirations but by a simple, single-minded desire to be close to the One who can ensure true rest.

In seeking to understand more deeply what God has revealed to us, we theologians make use of many complicated concepts and distinctions, but at the end of all our analyses God’s message to us is quite simple: “Stop your fruitless wandering. Stop chasing after the wind. Come to me like a child, and sit in my lap. Stay with me, and learn from me. I will calm your heart by giving you my own.”