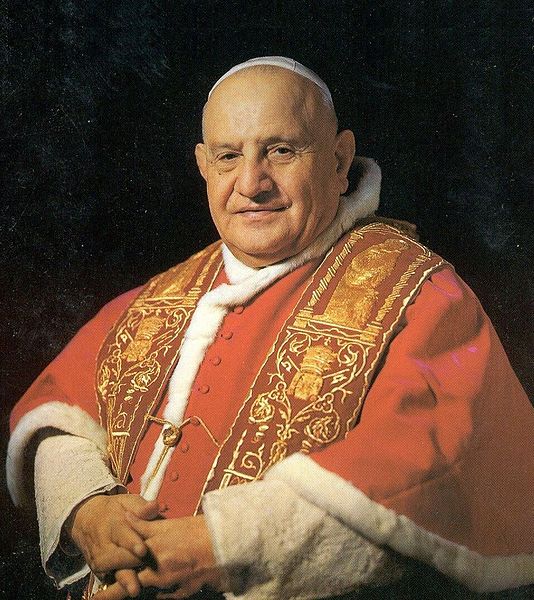

The popes are the in the news a lot today: Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI and our current Pope Francis canonized two popes from the recent past in a Vatican ceremony that many Catholics in the U.S. watched live even though it meant a middle-of-the-night screening. Even in San Diego, this story was front page news today. In this, our third CMT post (see the first here and the second here), I’m going back into the archives of the Boston Globe to learn about Pope John XXIII and how journalists of his own time recorded his achievements.

In the interest of full disclosure, I should warn you that this research was conducted in 2001 as part of a paper I wrote for a course I took with Fr. John O’Malley, S.J., at Weston Jesuit School of Theology. At the time, I was disgusted and saddened by the stories of the sexual abuse crisis and yet appreciative of the investigative journalism because it brought to light what had previously been clouded in secrecy. I knew the secular press could have a lot of influence, but I was also aware that the journalists and editors might have their own agenda. In the class with John O’Malley I was reading the documents of the Second Vatican Council and learning from Fr. O’Malley’s own lectures and first-hand accounts of his experiences as a young Jesuit. For my final paper, I combed through the archives of The Boston Globe, which had two daily publications during that time, selecting a representative eighty-five stories to analyze. When reading the articles, I looked for five things: (1) Location: Did the story make front-page news? Was it the primary headline? If not, where was the story placed?; (2) Competition: If the Vatican II coverage was not front-page news, what was? If it was, what stories did it beat?; (3) Tone: Was the tone of the article positive or negative? Hopeful or pessimistic? Praising or mocking?; (4) Clarity: Did the author use language too technical for a general readership? Was the article clear, understandable? (5) Accuracy: Was the article accurate in its historical or doctrinal explanations? Was it so heavily slanted so as to distort the truth?

The results of my research indicated that John XXIII’s initial announcement came as a great surprise to Bostonians, and resulted in great hope, some confusion, and unrealistic expectations. When the Council first began, coverage was extensive and positive; as the Council continued, interest declined. A major exception to this was the coverage of the death of John XXIII and the election of Paul VI, both of which consistently made the front page of both editions. In general, The Globe’s analysis focused on ecumenism, to the neglect of internal reforms–perhaps to appeal to a wider readership. I’ll review here only some of the stories that I’ve enjoyed re-reading as I reflect on the canonization of Pope John XXIII.

On January 26, 1959, the front page of the Boston Day Globe announced in its headline, “Pope Acts to Unite All Christians.” The subtitle reads: “Summons First Ecumenical (World-Wide) Council in Nearly A Century.” The tone of the article is one of excitement and wonder, as it explains to readers what is meant by an “ecumenical council” and tries to determine the pope’s motives for calling such a council. Calling the action “historic” and “unexpected,” the article suggests that the primary focus of the Council would be “uniting the Christian forces of the world,” and even goes so far as to note that non-Catholic churches “may be invited to participate in the council.” The article also predicts that one of the major subjects of the council will likely be the “reaffirmation of the Church’s stand against communism.” The editors write on the editorial page that Pope John XXIII is “a warm personality, a bold administrator, and a courageous spiritual leader.” In the next day’s paper, Cardinal Cushing told reporters that the council “is just what I would expect from good Pope John XXIII.” Some initial reactions proved to be too hopeful, or too unrealistic, like the excited expectations voiced by Reverend Shirley Goodwin, who is reported to have said that the pope “should consider inviting the World Council of Churches in Geneva and the National Council of Churches of the United States to participate in the Congress.” I found it interesting that in the first series of articles about Vatican II, no internal church reforms were specifically mentioned as expected points of conversation. Many Catholics seemed puzzled, questioning the need for such a council. After all, the church was in no period of great crisis. Yet Globe reporter William Callahan would later say, “this is a modern world, and the Church firmly intends to keep pace with it.” (10/11/1962).

The evening edition of October 11, 1962 led with the headline: “Pope Pleads for World Unity.” The Globe’s coverage included four full pages of articles and pictures, not including the editorial page. The front-page article by William Callahan called the atmosphere one of “pomp and splendor, reminiscent of the Middle Ages.” Callahan’s article stressed Pope John XXIII’s appeal for Christian unity with no mention of the goal of aggiornamento, or the updating of church practices, and no mention of the pope’s insistence that the council fathers take into consideration “the way in which [doctrine] is presented.” Instead, the coverage focuses on the hour-long procession, the portable throne on which the pope was carried, the excitement of the crowds gathered, and (of course) the weather (which was cloudy). The major theme from the opening address was that Pope John XXIII rebuked the “prophets of doom who see the modern age as only ruin.” I found it interesting that an article by Sheila Walsh noted that “it is a man’s world behind the bronze doors of St. Peter’s.” (10/11/1962, pg.5). Walsh noted that no women’s voices–not even those of the mother superiors of religious orders–would be heard at the so-called “ecumenical council.” She went on to write: “Although the council’s deliberations will cover topics ranging from marriage and education to Christian unity and women, no woman is eligible to take part in the historic church assembly.” Indeed, readers of The Globe had to wait until the third session of the council to hear of women participants, and even then, they were only observers. (9/13/1964).

Pope John XXIII met with over one thousand journalists on the first working day of the council, urging them to be conscientious in their reporting. “We look forward, gentlemen, to very happy results,” he told the “newsmen” gathered. “You are at the service of truth.” (10/13/1962).

In The Globe’s coverage of the first session of the council, the “clash” between liberals and conservatives was often a focus of the reporting, often pitting the pope against the Curia. The secret sessions were the subject of much intrigue, and the attending bishops were often characterized as politicians eager to either bring great change or sustain the status quo. On December 3, 1962, Pope John XXIII called a recess and declared that the second session would ensue on September 8 of the next year. But the pontiff did not live to see that day.

On June 6 1963, all Catholic school children in the Archdiocese of Boston had a holiday to mourn the death of their beloved pope. The Globe’s coverage of the pontiff’s sickness and death was extensive. The June 3 headline read: “EXTRA: POPE JOHN DEAD” and presented a large picture of him in the center of the front page. Comments ranging from “Pope John was one swell guy” to “We wonder why, when the ecumenical feeling is so simple, someone didn’t think of it long before Pope John,” were intermingled with details of his final words, last wishes, and the hour of his death. In his eulogy, Cardinal Cushing called the pope “a bridge-builder” and a “revolutionary pontiff.” (6/6/1963, A20). Other articles describe how he gave a new vision to the pontificate by ending papal seclusion, by respecting other religious leaders as his equal peers, and by continuing his pastoral ministry to the sick and imprisoned of Rome, despite his old age and papal responsibilities.” (6/3/1963, A11). Some of the articles indicate that international leaders expressed deep sorrow over the death of the pope, as in the article titled “Pope’s Death Mourned Even By Communists” (6/4/1963). One comment summed up the legacy of John XXIII with the title: “His Changes Can’t Be Undone.” (6/4/1963, A14).

In the rest of the council sessions, news from within the United States often took precedence over news from the Vatican. For example, when Pope Paul VI opened the second session on September 29, 1963, this news was overshadowed by competing news from Alabama: the racially motivated church bombings, Ku Klux Klan rallies, and Governor Wallace’s reaction to them. Other hot stories during the council years included United States involvement in Cuba, the assassination of President Kennedy, violence in Vietnam, and the desegregation of public schools. By the time the third session began, the story covering the council was tucked away on page 54, where Sanche De Gramont explains: “There is less excitement about this session, less foregathering of bishops plotting strategy, less hubbub in St. Peter’s Square as the 2300 council fathers arrive from their distant and not-so-distant sees. The council, one of the major religious events of our time, has almost become routine” (9/13/1964).

As the council came to a close, reporter Louis Cassels describes a number of key changes in church life and practice: new ways of worship, a decentralized governing body, revised attitudes towards other religious traditions, greater prominence given to the Bible, emphasis on the dignity of the laity, improvements in seminary education, and letting nuns wear modern dress. “Not all changes will be visible immediately,” he wrote, “but the die has now been cast, and the life of the Church for centuries to come will be shaped by the decisions made in St. Peter’s Basilica since October 11, 1962.” (12/7/1965, A11).

In a survey for “The Women’s Pages,” Bostonians were asked whether, if the Catholic ban on eating meat on Friday was lifted, they would change their eating habits. The conclusion: “The consensus seemed to be that women won’t have to worry much about changing Friday menus. Fish on Friday is a tradition.” Mrs. Ruth Keeley, an elderly woman, responded, “I’ll go on eating fish. It doesn’t matter to me.” Robert Conroy, a teenager, remarked, “I don’t think I’ll eat fish on Friday. But my mother still will.” Mrs. Helen Rafferty, a middle-aged woman, replied, “My husband wouldn’t let us eat anything else but fish on Friday.” Walter Mulrey, an elderly gentleman, asks, “Why should I change just because the pope says so?” Because of the mixed answers, the editors of the Women’s Page offered both fish and fishless recipes, to satisfy any family’s Friday menu needs (12/8/1965, pg. 42). But the variety of responses to this one relatively minor question (in comparison to the gravity of other church reforms) is an indicator that many people were just beginning to wrestle with the invitation to re-think, or even to change, some religious practices.

Looking back at The Boston Globe‘s coverage of the council can help us to understand (or for some readers, relive) the struggles and confusion, as well as the hope and joy, of that time in Catholic history. While the council is long over, the newspaper articles are stored away on microfilm, and the interpretation of the council contested, still we can appreciate the excitement of this time and come away with a renewed appreciation of the significance of the work of Saint John XXIII. Pope Francis has said of Pope John XXIII: “He was courageous, a good country priest, with a great sense of humor and great holiness.” Today David Cloutier wrote: “John XXIII understood what many, then and now, do not quite get: the Church does not need to be paralyzed with fear, anxiety, and defensiveness. The Gospel is one of joy. As is fitting in this season of resurrection, we can embrace as John did the greeting of the Risen Christ: “Do not be afraid.”” Amen to that!