Readings: Daniel 7:13-14; Psalm 93:1-2, 5; Revelation 1:5-8; John 18:33b-37

The “ruler of the kings of the earth” is also the “faithful witness” (Rev 1:5). He rules as the one whose words we can lean on fully: His “decrees are worthy of trust indeed” (Ps 93:5). To belong to Christ’s reign involves faith in truth’s priority over power as well as hope in truth’s ultimate vindication over all attempts to subordinate communication to the search for control, stability, and safety (even if these things are sometimes important).

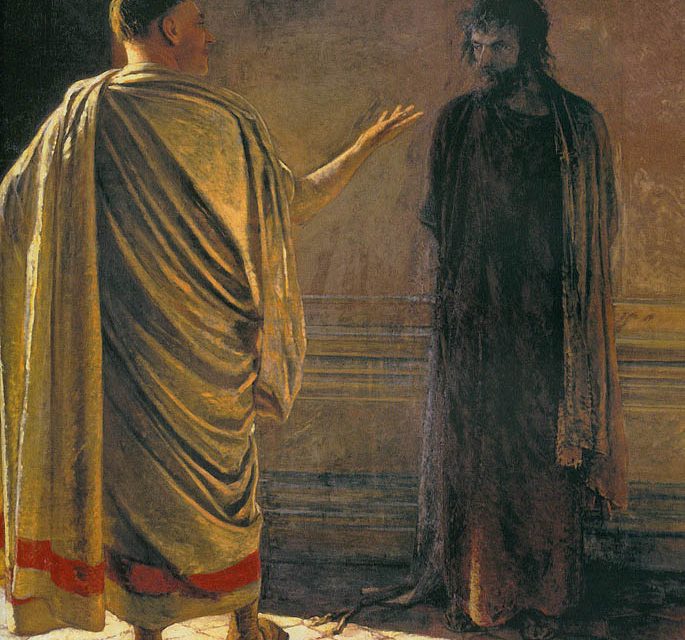

For Pilate, the conflicting claims posed by Jesus and his fellow Jews are forces to be managed to keep institutions afloat and prevent a riot. Jesus can tell that Pilate is not interested in taking personal responsibility for truth claims: “Do you say this on your own, or have others told you about me?” (Jn 18:34). From a certain perspective, Pilate’s strategy might seem diplomatic, open-minded, and even tolerant. But it results in throwing yet another innocent person under the bus and enabling the crowd’s vindictive scapegoating.

On the other hand, there are ways of siding with this innocent victim that give Pilate the last word: “If my kingdom did belong to this world, my attendants would be fighting to keep me from being handed over” (v.36). We do not yet belong to the truth if we are still “fighting” for its victory on the world’s own terms. We would not yet have submitted to the humanizing rule of the Son of man but rather to the beastly and dehumanizing empires that he has come to overthrow (reading Daniel 4 and 7 in full can be particularly helpful as context for this week’s first reading).

To belong to the truth is to listen to the voice of one who received and shared the truth with gratitude and love; for whom words were not weapons but a way to heal and nourish others; who spoke with a love that ran deeper than the wounds that afflict us and which so often prompt us to react defensively to news that threaten our security; and who absorbed these negative reactions onto himself ‘to the end.’ To belong to the reign of truth, then, is to accept and step into the vulnerability and weakness of truth and to suffer with the master who rules from the cross:

Everywhere in the history of religions, in various forms, we encounter the significant conflict between the knowledge of the one God and the attraction of other powers that are considered more dangerous or nearer at hand and, therefore, more important for human beings than the God who is distant and mysterious. All of history bears the traces of this strange dilemma between the non-violent, tranquil demands made by the truth, on the one hand, and the pressure brought to make profits and the need to have a good relationship with the powers that determine daily life by their interventions, on the other hand” (Joseph Ratzinger, Christianity and the Crisis of Cultures [San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2006], 98).

Good thing, then, that this faithful witness is also the “firstborn of the dead” (Rev 1:5). As the one who conquered death—a death he suffered as a witness to the truth against a beastly and manipulative empire—the God of truth not only stands with but vindicates and gives hope to all others who risk suffering and death by configuring their lives to the “non-violent, tranquil demands made by the truth.” If to share in the priesthood of Christ includes offering the world to God as a realm of grateful truth-telling, we do so in and through his own witness to a love that absorbs ‘to the end’ the fears that prompt us to misuse the truth. But we also do so with hope that such a sacrifice is not in vain. To be configured to the truth is also to step forward into a reign that is already here in the new life of the Risen One—and to turn away from a world of fear-based deceptions and propaganda that is already passing away.

The consequences of submitting to Christ’s truthful rule range widely. We could say much, e.g., about what it means for members of that kingdom to participate in the democratic process or make use of digital media. Here, I would like to focus on a more oblique example that I find important precisely because it is relatively small and mundane.

We are all familiar with the fear of being lied to, manipulated, and betrayed. We clearly face this fear when it comes to politics and personal relationships. But that fear also rears its head in ways that may well prove formative over the long haul precisely because they are woven so closely into the challenges of daily life. Consider your own cumulative set of experiences dealing with, e.g., hiring a contractor or repair professional, taking your car to the shop, leaving your child temporarily under the care of other adults, or in any other way entering into an agreement with another person who promises to be trustworthy and adequately skilled in the provision of a certain good.

The personal act of pledging trust is important in part because that person’s work has subjective worth as the act of a free human being made in God’s image (see John Paul II’s Laborem exercens). But it also matters because there is really only so much that institutional instruments can do to protect and restore justice in many of these contexts. Attempts to circumvent our reliance on personal trust may easily make matters worse. For example, if you are considering hiring someone to repair your furnace because it failed in the middle of winter, you now enjoy numerous review websites where previous customers can rate the skilled professionals you are considering. Of course, such services also allow users to ruin the good reputation of businesses that actually do deserve our trust. To fight back, some contractors have started to include non-disparagement clauses in their contracts and to take legal action against customers who post strongly negative reviews. It does not take much imagination to see how these instruments too could become a means of injustice. Nor is it clear that the cumulative effect of these developments is a culture where the choice to trust another human being is any less costly or risky. Rather, it seems we have largely upgraded the arsenal of weapons to be used in what we construe, with increasing consistency, as a kind of war.

The reasons for so arming ourselves, of course, are entirely understandable. Although for a privileged few the only possible losses are unnecessary luxuries, for many of us getting swindled by a contractor, customer, or car repair shop could jeopardize our ability to secure basic necessities. Often enough, our own or our children’s personal safety are also at stake. We should also note that betrayal can inflict a more direct psychological wound regardless of the gravity of the objective losses incurred. To be swindled is, among other things, to be tempted strongly towards global doubt as to the trustworthiness of the world around us. It can take a great deal of care not to overindulge in such ‘realism’ and the cynicism that often comes with it. Such wounds may not necessarily empower us to consider carefully whether the protective posture we now wish to embrace will be worth the sacrifices we will suffer from ceasing to be as vulnerable with others.

For example, as an adoptive parent I am deeply aware that most (if not all) potential adoptive situations put birth parents as well as adoptive parents at a huge risk of being deceived or manipulated by the other side or by the professionals counted on to see the process through in a fully just and humanizing manner. Moreover, each side’s own history of suffered betrayals is liable to hover over their deliberations. It is, of course, perfectly appropriate to seek measures that ensure accountability and reduce the risks involved. But at the end of the day, the adoption simply will not happen if either party is too committed to guarding themselves against being lied to. In many cases (really, the only cases where an adoption should ever happen outside of the foster care system) this would mean giving up on what is likely to be the better course forward for the child as well as the birth parent(s). The wounds left by our previous suffered betrayals can be a hindrance as much as an asset to our practical reasoning.

It may be helpful to consider how these variously important or trivial instances of potential or actual swindling can sediment over the long course of our day-to-day lives into an emotional or imaginative habit that requires much fuller attention. I strongly suspect that many of us, each in our own way, experience significant portions of our lives under a gnawing, diffuse, and often peripheral fear of ‘being had.’ The danger identified by this fear is often real. But our reaction to such fear cannot be exempt from scrutiny. This is especially so if our response consists more centrally in protecting ourselves against lies than in building a world where the free exercise of trust can thrive. At a certain point, our response to such fear can only be properly described precisely as the kind of “fighting” mentioned in John 18—i.e., fighting to protect the truth from being betrayed, fighting that guards the truth in ways that imply despair of truth’s ultimate vindication over arbitrary power, fighting that says “no” to the forgiving and gracious personal vulnerability shown by the truth incarnate when he was put on trial by the world.

All this to say: There must be a way for us to learn to move from this fear not only towards more objective accounts of the risks at hand, but also (and most importantly) towards ways of extending trust to our neighbors despite those risks. The God of truth rules precisely as the one who spoke vulnerably to us while we were yet sinners prone to betray and misuse him as we grasped for control over our future in a risky world. It stands to reason that members of that kingdom of truth should strive to emulate Christ’s own way of speaking.

Featured image: Nikolai Ge, “What is Truth?” Christ and Pilate, 1890; Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain.